Governors have employed system-wide approaches and innovative procedures to protect health during the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper looks at ways to position the COVID-19 children’s vaccine response to ensure equitable access and increased uptake.

(Download)

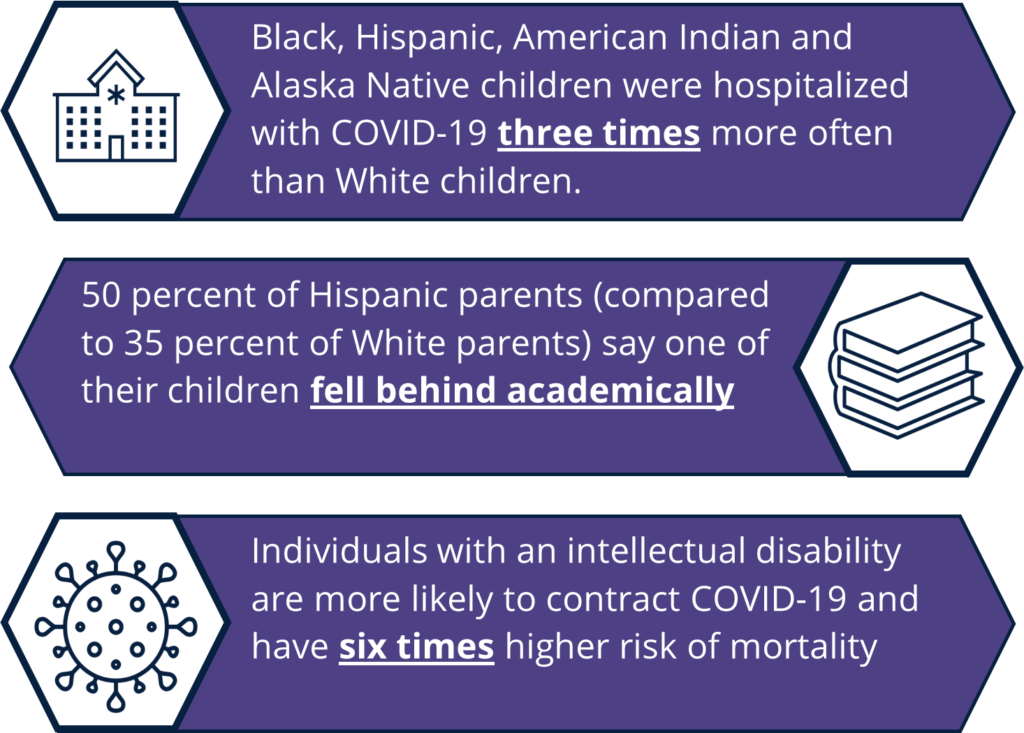

During the first year of the pandemic, COVID-19 cases in children were primarily asymptomatic or mild. Children’s infections rose during the delta variant surge in July and August of 2021, leading to more COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations for those under 18. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), children and adolescents are four times more likely to be hospitalized in states with vaccination rates under 50 percent compared to those with higher rates. Children with severe COVID-19 may require hospitalization, intensive care or even ventilation. In rare instances, children have died. Like adults, children with underlying health conditions and within communities of color are at greater risk of severe illness. Vaccination can protect the nearly 49 million children in the United States under the age of 12 against COVID-19, especially the risk of severe illness, hospitalization and death. At the time of this publication, a pediatric COVID-19 vaccine is available for children as young as 5.

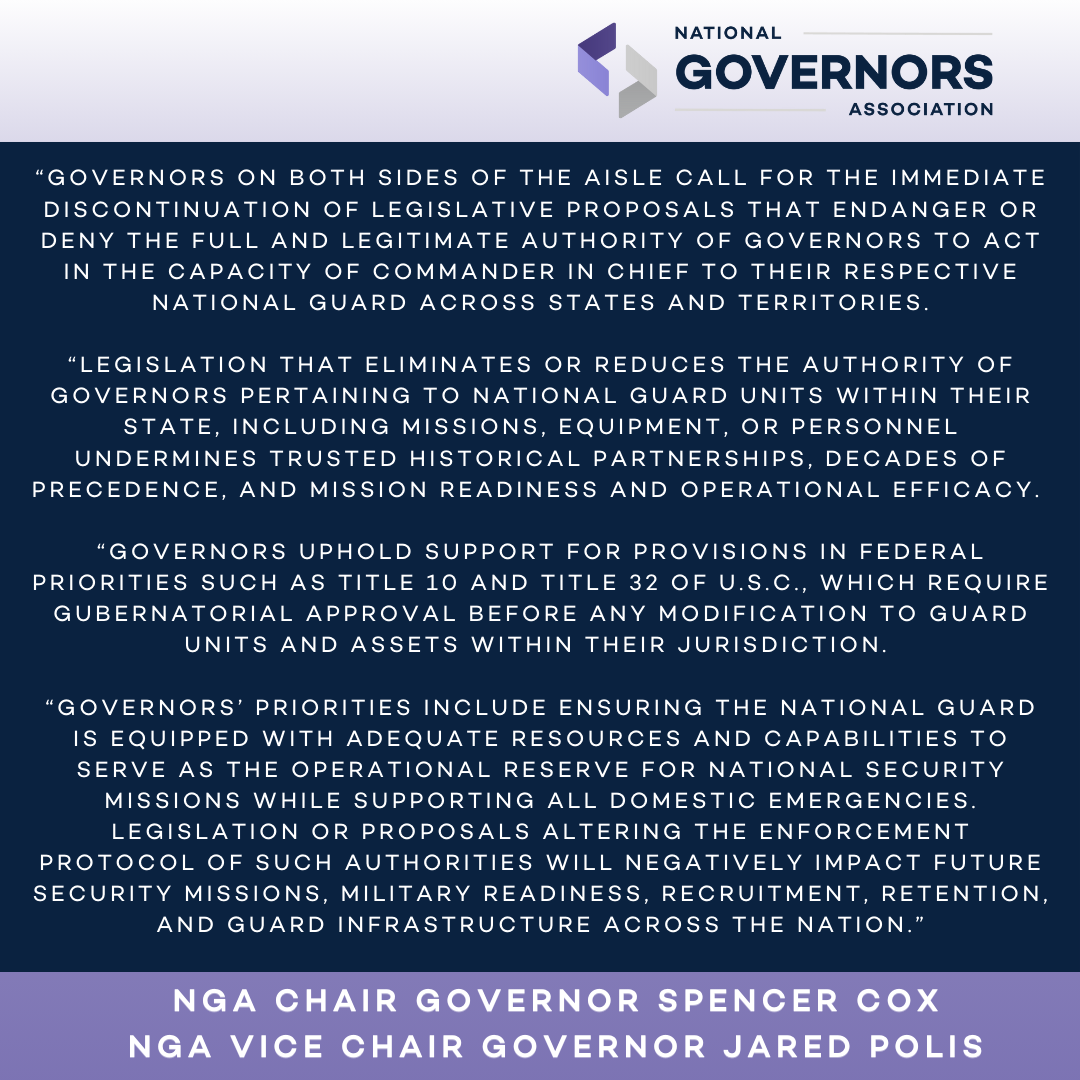

Since the pandemic began, Governors have been on the front lines, creating and executing policies to strengthen the nation’s COVID-19 response. Governors have employed system-wide approaches and innovative procedures to protect health in this and other public health emergencies, such as the H1N1 outbreak. As the nation moves into a new phase of the pandemic, Governors can position their state’s COVID-19 children’s vaccine response to ensure equitable access and increased uptake by:

- Centering all aspects of COVID-19 vaccine response around equity;

- Building COVID-19 vaccine confidence through partnerships and a focus on facts;

- Leveraging existing vaccination infrastructure to meet children where they are; and

- Establishing systems to increase capacity for storage and administration.

Center All Aspects Of Covid-19 Vaccine Response Around Equity

Historically underserved populations, including communities of color, noncitizen immigrants and individuals with disabilities, have faced additional barriers to care throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Black, Hispanic and Asian children have been more likely to be infected with COVID-19, but testing rates are lower among these groups than for White children. People with disabilities, including children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN), have been impacted by inaccurate data collection, inaccessible testing, difficulty finding information relevant to a variety of conditions and a lack of alternative text on COVID-19 webpages or closed captions on videos and webinars.

Governors, Title V Directors, Health Officers and other state officials may consider the following to center the state’s vaccine response around equity, reduce disparities and prevent additional loss to COVID-19:

- Identify barriers to access for communities high on the social vulnerability index by hearing from community representatives directly and often to address issues in a timely manner.

- Eliminate identification requirements to receive a vaccination to reduce barriers and ensure this is communicated to providers, health care systems and payors in the state.

- Convene a cross-sector council of stakeholders, including leaders from communities of color, disability advocates, community-based organizations (CBOs) and community health workers (CHWs).

- Leverage low-tech strategies to engage families, e.g., partnering with CBOs to set up sites in high-impact areas and allow walk-in options for families to receive vaccines in one location.

- Encourage employers to provide paid-time-off for parents to take their children to get vaccinated for COVID-19 and to catch up on routine childhood vaccinations.

- Urge school districts to host school-located vaccination clinics and allow time for students to get vaccinated during class time.

- Ensure health data collected includes race, gender, language and other cultural factors to identify gaps in service and be able to address them, especially for those facing multiple barriers.

- Provide vaccination materials, including town halls in multiple languages in plain language.

- Create outreach and education campaigns to help individuals understand where and how to obtain the vaccine and that it is available at no cost to everyone regardless of insurance status.

Equity Resources

- Advancing Immunization Equity: Recommendations | National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC)

- American Sign Language Video Series | CDC

- Caring for Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic | American Academy of Pediatrics

- Carrying Equity in COVID-19 Vaccination Forward: Guidance Informed by Communities of Color | CommuniVax

- Communication Toolkit for Migrants, Refugees & Other Populations |CDC

- COVID-19 Factsheets | Community Health Literacy Project

- Easy to Read COVID-19 Materials | CDC

- Equity in Vaccination: A Plan to Work with Communities of Color Toward COVID-19 Recovery and Beyond | CommuniVax

- Guidance for Direct Service Providers for People with Disabilities | CDC

- Leveraging Community Expertise to Advance Health Equity | Urban Institute

- People with Certain Medical Conditions | CDC

- Prioritizing Equity in COVID-19 Vaccinations | NGA

- State Strategies to Increase COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in Rural Communities | NGA

- Strategies for Reaching People with Limited Access to COVID-19 Vaccines | CDC

- Strategies for States to Drive Equitable Vaccine Distribution and Administration | State Health & Value Strategies (SHVS)

- Vaccine Considerations for People with Disabilities | CDC

State and Local Examples

In Connecticut, East Hartford High School permitted eligible students to get vaccinated during the school day through a community health center. The school also provided over 1,000 students transportation to the clinic.

Massachusetts launched a Vaccine Equity Initiative to engage communities hardest hit by COVID-19, build trust, identify barriers and increase access to vaccines.

The Minnesota Department of Health provided information for caregivers of adolescents with special health care needs that includes specifics of what is in Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, specific accommodations individuals might request and responses to potential concerns.

New York passed legislation granting public and private employees paid leave to get a vaccine.

The Washington Department of Health COVID-19 Resource website includes resources available in over 50 languages.

Build Covid-19 Vaccine Confidence Through Partnerships And A Focus On Facts

Preventing the spread of false claims is one of the first steps in building vaccine confidence. False claims about the COVID-19 vaccine have been strategically targeted toward specific populations, like parents, to cast doubt on the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness. Governors can lean on trusted messengers who are considered impartial, transparent and consistent to share facts about the vaccine and address peer concerns. For most Americans, especially parents, health care providers are the most trusted sources of information about vaccines. The acceptability of a message is also dependent on the content and context, meaning campaigns are more successful when tailored to a specific audience.

Governors and state officials may consider the following to build vaccine confidence:

- Support peer-led and neighborhood-based opportunities for community conversation through collaborations with CBOs and CHWs.

- Engage pediatricians and specialists early and often to ensure they have the most up-to-date information on the vaccine to share with patients and parents.

- Update media campaigns often to reduce fatigue and capture attention through visuals, emotion, personalized content and/or positive headlines.

- Partner with state and local health departments to develop clear, positive COVID-19 vaccine messaging campaigns that engage a variety of audiences.

- Direct state and local health departments to engage pediatricians and other children’s health care providers to develop a network of vaccinators with a consistent message about vaccine safety.

Communications And Messaging Resources

- Children, Schools, and Vaccines: Communicating to Parents | de Beaumont Foundation

- Communication Materials for COVID-19 Vaccines | CDC

- Communication Strategies for Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines: Addressing Variants and Childhood Vaccinations | The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine

- Communication Toolkit for Limited-English-Proficient Populations | CDC

- Community Partners Offer Key Insights to Health Departments for Increasing Vaccine Confidence | Association of State and Territorial Health Officials

- COVID-19 Vaccine Incentives | NGA

- COVID-19 Vaccine Community Features | CDC

- Disinformation and COVID-19: How State and Local Officials Can Respond | Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- Four Message that can Increase Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines | Behavioral Insights Team

- Messaging Recommendations | Ad Council and COVID Collaborative

- Myths & Facts about COVID-19 Vaccines | CDC

- Reducing Vaccine Hesitancy for People Living with Disabilities | ASTHO

- Resources & Toolkits | We Can Do This

- Teaching About Vaccines | Educators 4 Social Change

State and Local Examples

The Kansas Department of Health and Environment developed a manual for primary care physicians on creating messages to encourage COVID-19 vaccination.

The Maryland Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities created the Community COVID-19 Vaccination Project (as part of the Maryland Vaccine Equity Task Force) to award grants to 30 CBOs to support vaccine education and outreach. The grants are prioritized to specific zip codes with low vaccination rates.

The Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services created an interactive map called Share Your Shot for residents to share positive experiences about receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services partnered with NC Counts Coalition to conduct regional outreach, canvass and provide resources and increase vaccinations among communities of color.

Leverage Existing Vaccination Infrastructure To Meet Children Where They Are

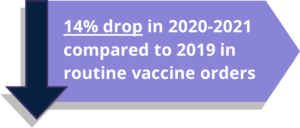

Governors can leverage existing structures, such as Title V departments, and provider relationships to employ strategies to vaccinate children in their states. A large portion of vaccine providers are enrolled in the Vaccines for Children program (VCF), which administers vaccines at no cost to children under 19 years old under certain circumstances like Medicaid eligibility or lack of insurance. These providers have an intimate knowledge of vaccination campaigns due to the number of routine immunizations children require. Engaging VFC providers can also create synergy for catching up on routine childhood immunizations that fell behind during the pandemic.

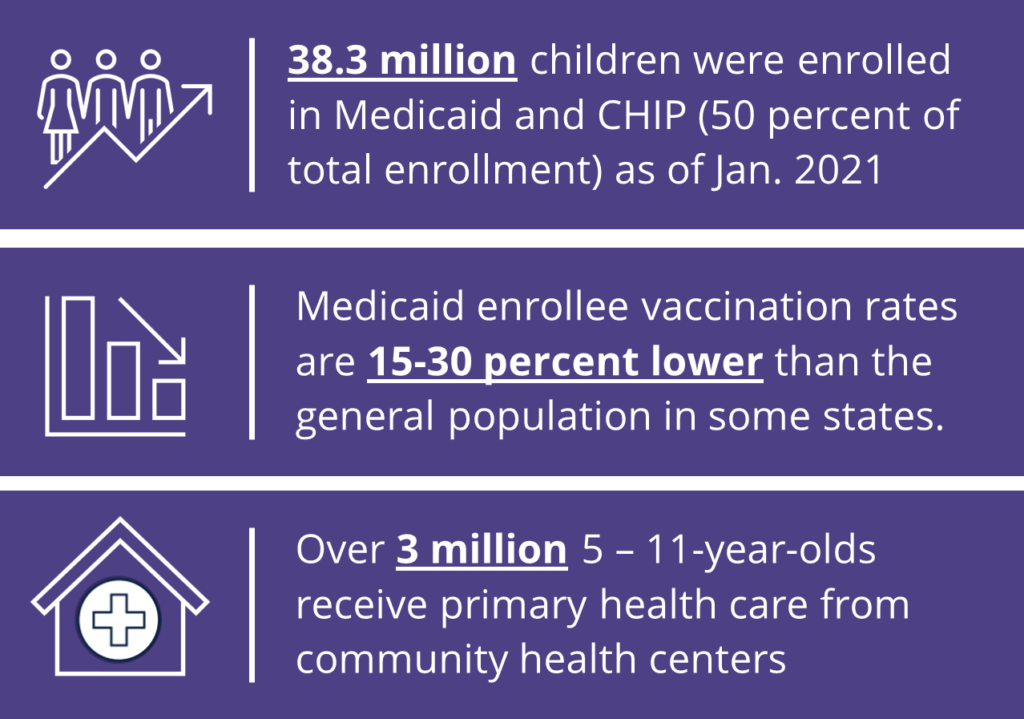

Children receive vaccines or vaccine information at a variety of locations outside of their doctor’s office, including school health clinics, local health units, pharmacies and clinics through programs like Head Start, Early Head Start or Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC). State officials can utilize these institutions as well as public health insurance programs, like Medicaid , the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and their contracted managed care organizations (MCOs), to connect children and families to COVID-19 vaccinations and increase uptake.

Governors and state officials may consider the following to leverage existing vaccination infrastructure:

- Leverage existing structures and provider relationships to enroll vaccinators, distribute the vaccine and meet children and families where they are for the COVID-19 vaccine and missed routine vaccines.

- Request providers for CYSHCN to vaccinate or provide accurate information to patients and families, including audiologists, interpreters, occupational therapist, ophthalmologist/ optometrist, physical therapist, speech pathologist/speech therapist and others.

- Engage the maternal and child health workforce, including doulas, CHWs and home visitors, to provide factual information about vaccines to their patients and clients.

- Support local health departments holding vaccination clinics or events in high-impact settings, including but not limited to kindergarten enrollment, pre-k, WIC appointments, Head Start, Early Head Start, after-school programs and other community children’s programs.

- Facilitate collaboration between state and local health departments and the state child/family services system to bridge gaps in vaccine access.

- Encourage schools to hold school-located vaccination clinics to provide a convenient location for students, family and community members to receive a vaccine.

- Partner with departments of education and school districts to promote vaccine confidence among teachers, school staff and parents by providing COVID-19 vaccination resources, asking for their involvement in school-located clinics, wearing COVID-19 vaccination stickers, displaying COVID-19 educational posters and preparing them to address misinformation.

- Collaborate with Medicaid and contracted MCOs to reach children and families in areas with low vaccination rates.

- Encourage providers to utilize the state’s immunization information system/registry to facilitate identifying disparities in vaccination coverage for COVID-19 and routine vaccines.

Routine Childhood Immunization Resources

- Catch-Up to Get Ahead Toolkit | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- Routine Immunization Media Materials | Association of Immunization Managers

- Resources to Encourage Routine Childhood Vaccinations | CDC

Vaccine Site And Access Resources

- 12 COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies for Your Community | CDC

- Considerations for Planning School-Located Vaccination Clinics | CDC

- COVID-19 Information for Health Departments | CDC

- Expanding Vaccination Site Accessibility | ASTHO

- Guide to On-Site Vaccination Clinics for School | We Can Do This

- How Schools Can Support COVID-19 Vaccination | CDC

- Mobile Vaccination Resources | CDC

- Coverage and Reimbursement of Vaccines, Vaccine Administration, and Cost-Sharing under Medicaid | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- COVID-19 Vaccination Program Operational Guidance |CDC

- Modernizing Immunization Information Systems | NGA

- State Strategies for Engaging and Leveraging Primary Care Providers as COVID-19 Vaccinators | NGA

- Ways Health Departments Can Help Increase COVID-19 Vaccinations | CDC

State and Local Examples

The California Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) linked to the state’s immunization registry to share vaccination information with state MCOs to target outreach efforts to those not yet vaccinated.

The Kansas Department of Health and Environment created a detailed strategy document for vaccine providers to hold community vaccination events.

The North Dakota Department of Health provides an online survey for schools to schedule vaccine clinics on-site.

The Ohio Department of Medicaid reserves ~3 percent of MCOs payments from the state that plans can earn back by improving certain health outcomes, including closing the childhood vaccination gap. The state has also employed vaccine incentives for individuals 12 and older enrolled in MCOs.

Establish Systems To Increase Capacity For Storage And Administration

Initially, the adult vaccine rollout was met with distribution challenges due to cold chain storage requirements, large shipment quantities and expiration limitations. The distribution complexities have eased as cold chain requirements and other barriers have become less rigorous. Although these issues are not anticipated with the pediatric COVID-19 vaccine rollout, special dosing and distribution requirements may cause logistical challenges. Governors can plan to make the vaccine available at many sites, including smaller provider practices, to increase accessibility and offer flexibility.

Governors and state officials may consider the following to establish systems to increase storage and administration capacity:

- Create a site to break down shipments so providers can receive only needed doses and prevent waste.

- Develop a centralized ordering system for state providers to order vaccines and supplies.

- Adjust existing systems to include COVID-19 vaccine and supply ordering.

Pediatric COVID-19 Vaccination Logistics

- Pediatric product will have new packaging, new preparation, and a new national drug code; however, the active ingredient is the same.

- The current product for adults and adolescents should not be used in children.

- The packaging configuration will be 10-dose vials in cartons of 10 vials each (100 total).

- Product can be stored for up to 10 weeks at 2 to 8°C (normal refrigeration) and 6 months at ultracold temperatures of -90 to -60°C. Doses must be used within 6 hours once opened.

- Pharmacies participating in the Federal Retail Pharmacy Program (FRPP) will be able to order vaccine to select locations.

Acknowledgements

NGA Center would like to acknowledge and thank national experts and state officials who granted informational interviews and provided content for this publication. The NGA Center would also like to thank the Health Resources and Services Administration for their generous support through this project.

Recommended Citation Format

LeBlanc, M. & Roy, B. (2021 November). COVID-19 Vaccines for Children: Exploring Immunization Strategies for Individuals Under 12. Washington, DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices.