This brief outlines eight strategies to promote equity throughout the reemployment and workforce service delivery process.

(Download)

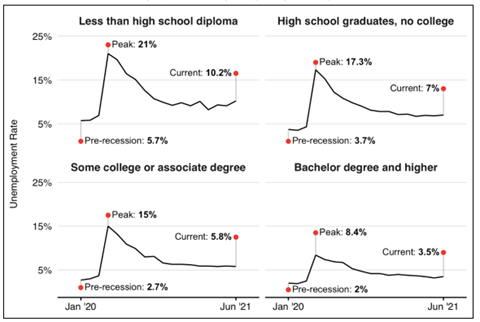

The COVID-19 pandemic illuminated many inequities historically imbedded in American healthcare, workforce, and education systems, among others. While the national unemployment rate has declined since its peak at 14.8% in April 2020, rates of return to work, workforce participation, and earnings for some industries and individuals have not recovered as quickly. For example, the unemployment rate of young workers, women, workers with lower educational attainment, part-time workers, and racial minorities remains higher than their counterparts as the economy reopens.

Unemployment Rates by Education Seasonally Adjusted Monthly Data: January 2020 to June 2021

Providing workforce services in a way that addresses these disparities is an economic and moral imperative. Research shows that a more diverse workforce leads to higher economic growth, more participation in the consumer market, a more qualified workforce, and more creativity and innovation in business. State workforce systems play an important role in creating equitable workforce systems by ensuring all jobseekers can access training and employment via an accessible, coordinated workforce system. Governors have a unique opportunity to emphasize and prioritize equity as a driving value of these systems. To advance equity, workforce systems should examine institutional structures and barriers to participation that contribute to inequities across age, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, economic status, educational attainment, immigration status, industry sector, and worker classification.

This brief outlines eight strategies to promote equity throughout the reemployment and workforce service delivery process.

- Launch a task force, initiative, or cabinet-level position to drive sustained action toward shared equity goals.

- Create a definition of equity to apply to goals, programs, evaluation, and more.

- Develop a goal to achieve equity in service delivery and drive action toward shared metrics of success.

- Gather and analyze data to identify gaps in service delivery and to track outcomes.

- Target reemployment, training, and support services to populations most in need.

- Engage stakeholders to inform decisions and gather feedback on policies and programs.

- Examine policies and procedures that may contribute to inequity and modify them to make programs more accessible.

- Create or strengthen partnerships to reach more populations and leverage expertise and resources that can assist in reaching these groups.

For more information about state workforce recovery strategies, please refer to the National Governors Association State Roadmap for Workforce Recovery.

Strategies and Considerations for Improving Equity in Reemployment and Other Workforce Services

1. Launch a task force, initiative, or cabinet level position to drive sustained action toward shared equity goals.

Organizing a dedicated group of policymakers or naming one leader to focus on and advance equity goals promotes accountability, signals that equity is a priority, and helps coordinate and streamline efforts.

- The Illinois Workforce Innovation Board created an Equity Task Force to develop recommendations for reducing inequities in Illinois’ workforce and education systems. The Task Force has three priorities:

- 1. Examine programs, policies, and practices to infuse issues of equity and inclusion into them;

- 2. Assess and recommend education and workforce tools that can track program access and outcomes and disaggregate data to reveal disparities in how policies and program delivery impact different groups and;

- 3. Make recommendations regarding inclusive and diverse approaches to organizational capacity, including professional development to ensure use of an equity lens in serving diverse populations.

- As of March 2021, 13 states had created diversity, equity, and inclusion cabinet-level positions, and 26 Governors led other gubernatorial initiatives focused on these issues, such as creating a steering committee, council, or task force, and signing an executive order.

- In Arizona, the Nineteen Tribal Nations launched their own Workforce Development Board comprised of leaders of each tribe. Through this collaborative structure, the Nineteen Tribal Nations promote a workforce system based on listening, dialogue, and consensus to build and grow their investment in education and career-building services. Representatives from the Arizona NGA Workforce Innovation Network state team included these Tribal areas in their state action planning to develop a more coordinated and streamlined service delivery model.

2. Create a definition of equity to apply to goals, programs, evaluation, and more.

Defining equity and the equitable outcomes the state is trying to achieve is a critical first step to assessing gaps and developing more equitable reemployment strategies. This should include clearly identifying which historically excluded or marginalized groups the state’s work is focused on.

- In January 2021, the NGA Center released the State Roadmap for Workforce Recovery that offers a framework for how states can organize state workforce response and recovery activities. The resource defines equity as “the fair and impartial inclusion of people of color and other traditionally marginalized or underrepresented groups in the workforce.”

- Colorado’s Workforce Development Council created the 2020 Colorado Talent Equity Agenda to address the disparities in educating, training, hiring, and promoting Colorado’s workforce, including a definition of racial equity in workforce development: “Racial equity is achieved when race or immigration status is no longer correlated with one’s outcomes; when everyone has what they need to thrive, no matter who they are, the color of their skin, or where they live.” The Agenda also includes five areas for sustained action, including 1) career navigation and advancement, 2) closing the digital divide, 3) postsecondary credential attainment, 4) unemployment, and 5) equitable hiring, compensation, and promotion.

3. Develop a goal to achieve equity in service delivery and drive action toward shared metrics of success.

Creating an equity goal helps strategically align state activities and strategies for improving access to education, work, or training.

- Connecticut’s Governor’s Workforce Council created a workforce strategic plan in October 2020 that included goals to close equity and access gaps in workforce services. The plan also includes strategies and metrics for expanding equitable access to childcare, reducing transportation barriers, expanding behavioral health services, and reducing the effects of benefit cliffs.

- The Oregon Metro Regional Government created a Strategic Plan to Advance Racial Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, including five unique goals to advance equity.

4. Gather and analyze data to identify gaps in service delivery and track outcomes.

The NGA State Roadmap for Workforce Recovery suggests three phases of data analysis for advancing equity: 1) collect data on barriers preventing equal access to programs and resources and track relevant outcomes; 2) encourage all departments and community providers to conduct a formal equity analysis to determine service gaps; and 3) use data on service gaps to set unique goals for access and adoption of essential support services across populations.

- The Minnesota Employment and Economic Division launched the Uniform Report Card showing real-time activities and employment outcomes for select workforce development programs by education level, race, ethnicity, gender, and geography.

- The Missouri Governor’s Office led a cross-agency data initiative to develop and utilize social impact dashboards to share social services data to improve service delivery. These dashboards show the use of social services overtime in each county.

- Washington is establishing a system-level dashboard that reflects progress towards family-sustaining wage levels, disaggregated by populations and regions. Dashboard metrics and targets will reflect cost of living differences between and among regions. Because the new targets will require improved service integration to be achieved, administrative agencies and program providers are developing common intake, service planning, and case management tools.

5. Target reemployment, training, and support services to populations most in need.

While this list is not exhaustive, and subgroups are often intersectional, common populations that face disproportionate barriers to participating in the workforce include formerly incarcerated persons, tribal communities, persons with a disability, persons of color, veterans, and women. Several states have taken action to maximize eligibility for and access to additional support services under existing federal programs for these populations during the reemployment process.

- Delaware established an Office of Women’s Advancement and Advocacy through House Bill 4 to promote the equality of women and to facilitate collaboration between government and businesses to eliminate gender-based bias.

- Illinois is applying funds awarded from the NGA Workforce Innovation Fund to develop an action plan and pilot a coordinated-service delivery model to offer training and employment placement for veterans. The state strategy, coordinated across seven agencies, seeks to gather new data on the state’s veteran population, with an emphasis on better understanding the needs and location of transitioning service members, disabled veterans, and homeless veteran populations. As part of this, Illinois is analyzing data, such as results from focus groups to better understand barriers in accessing services and navigating programs. The goal is to map coordinated service delivery across state agencies to enable policy and partnerships that support better outcomes for veterans.

- New Mexico used U.S. Department of Labor Dislocated Worker Grant funds to initiate a transitional jobs program to help non-violent offenders scheduled for early release due to COVID-19 successfully transition into work.

- Oklahoma Human Services offered 60 days of subsidized childcare to Oklahomans who are looking for work due to the loss of employment during the COVID-19 crisis.

6. Engage stakeholders to inform decisions and gather feedback on policies and programs.

Over the past decade, policymakers and practitioners have increasingly focused on the need to regularly connect with people left out of community engagement activities, including the elderly, individuals experiencing homelessness, citizens reentering public life after incarceration, people with limited access to the internet or with limited computer literacy, people with disabilities, immigrants, people working several jobs or working during nontraditional hours, and people who are English-language learners. Directly engaging these stakeholders allows states to gather qualitative data on how programs operate and identify areas for improvement.

- Alabama conducted a survey of unemployed and underemployed workers to measure awareness and attitudes towards new job retraining programs. The sample results were weighted to be representative of the gender, age, race, and education makeup of the population. The survey was cited in the Governor’s Office of Education and Workforce Transformation’s report.

- Missouri launched the Jobs Centers of the Future initiative to improve workforce outcomes by tracking customer progress as they move through the job-seeking process. As part of this effort, the state launched a series of focus groups in partnership with local areas to engage jobseekers and frontline staff to inform programmatic changes.

7. Examine policies and procedures that may contribute to inequity and modify them to make programs more accessible.

While local workforce development boards are responsible for developing and implementing policies to serve the needs of jobseekers and families, states can provide training and technical assistance to local areas to promote a review of procedures and policies that may contribute to equity in reemployment and training.

- Several states, including Arizona and Maryland, have reviewed local American Job Center policies to examine barriers to access, including policies that prohibit children on-site, hours of operation, intake processes, and more.[v]

- California’s Assembly Bill (AB) 104 and Adult Education Block Grant (AEBG) urged regional community college consortia to adopt policies and practices that promote program integration, “seamless transitions”, and other “joint programming strategies between adult education and career technical education”, including with programs such as the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act.

- Connecticut’s Department of Aging and Disability Services and Department of Labor serve clients in coordination with the Regional Workforce Development Board in the American Job Centers. In response to COVID-19, many transitioned in-person services to online workshops and virtual conference meetings, while also creating accessible online job fairs and programs allowing participation in weekly virtual orientations, job clubs, workshops, and individual conference calls with career counselors.

- The nonprofit United Women’s Empowerment launched a task force to analyze what hinders Missouri women from finding jobs. The task force will host town hall meetings and then produce a report with policy recommendations for policymakers in the Fall of 2021.

- South Carolina introduced a training program to strengthen the capacity of American Job Centers staff to effectively serve jobseekers and businesses. The program focused on building a common understanding of the workforce system, including key partners and clients. More than 700 staff have been trained resulting in a greater understanding of how to make connections with partner programs, facilitate effective referrals, and better serve individuals with barriers to employment.

8. Create or strengthen partnerships to reach more populations and leverage expertise and resources.

The public workforce system is structured to facilitate partnerships across many workforce development organizations. Given limited resources, partners are essential for meeting the complex needs of families and allow a variety of perspectives and strengths to be recognized as they work together to support programmatic success. The following are common partnerships that support equity in employment, including community-based organizations, community colleges, employers, and labor unions.

- The New Jersey Career Pathway Partnership for Employment Accessibility (CPPEA) aims to apply a coordinated systemic approach to encourage career pathway inclusion for people with disabilities. This developing model includes coordinated program recruitment and outreach services to VR eligible individuals and employers, pre-enrollment services, benefits counseling, career pathway pilot navigation support teams and placement services for internships, pre-apprenticeships, registered apprenticeships, and competitive-integrated employment. CPPEA serves to enhance awareness and participation of public sector employers in the State as a Model Employer effort and promote ongoing enhanced employer engagement and alignment with county colleges. Core members include the New Jersey Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services, Office of Employment Accessibility Services, Division of Workforce Development from the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development, the New Jersey Division of Developmental Disabilities, the New Jersey Council of County Colleges, and other community partners.

- Montana’s Disability Employment and Transition Services Division is responsible for facilitating relationships across partners to ensure customer needs are being met across all state entities. Key partners include the state Vocational Rehabilitation program, community rehabilitation providers, WIOA Title I providers, and Montana’s K-12 education system. The Vocational Rehabilitation program also contracts with community rehabilitation providers and school districts to deliver training and employment services to customers. This statewide provider network is well-established and provides ongoing training and support to help local partners serve those with disabilities.

- The Tennessee Talent Exchange, a partnership between Hospitality TN, Tennessee Retail, and the Tennessee Grocers and Convenience Association, places workers displaced from the hospitality industry into positions in grocery, retail and logistics industries through an online platform called Jobs4TN.

- In Vermont, the United Way of Chittenden County convened Working Bridges, an employer-led collaborative that offers support services including training, social service referrals, tax preparation, and transportation to workers in select industries.

- Washington used their COVID-19 National Dislocated Worker Grants to partner with local workforce areas, economic development agencies, Tribal governments, community-based organizations, and agriculture businesses and workers to create a flexible food security ecosystem to help redistribute fresh produce, subsidize employment, and support food banks during the pandemic.

Additional Resources to Advance Equity in the State Workforce System

- State Roadmap for Workforce Recovery (NGA Center for Best Practices)

- State Economic Recovery Agendas (NGA Center for Best Practices)

- Governors’ Role in Promoting Disability Employment in COVID-19 Recovery Strategies (NGA Center for Best Practices)

- State Solutions for Supporting the Return to Work and Filling Open Jobs (NGA Center for Best Practices)

- Equity Indicators Tool (CUNY Institute for State and Local Governance)

- WIOA Performance Targets: Incentives to Improve Workforce Services for Individuals with Barriers to Employment (The Center for Law and Social Policy)

- Closing Workforce Equity Gaps (Emsi)

- Five Things Public Workforce Systems Should Do Now to Advance Racial Equity (Heartland Alliance)

- Change and Continuity in the Adult and Dislocated Worker Programs under WIOA (Mathematica)

- National Equity Indicators (National Equity Atlas)

- Advancing Workforce Equity: A Guide for Stakeholders (National Fund for Workforce Solutions)

- Race and the Future of Work (National Fund for Workforce Solutions)

- Enhancing Intake to Improve Services: Collecting Data on Barriers to Employment (National Reporting System for Adult Education)

- Family-Centered Approaches to Workforce Program Services (The Urban Institute)

- Work Matters: A Framework for States on Workforce Development for People with Disabilities (National Conference of State Legislatures and Council of State Governments

This resource is a product of the NGA Workforce Innovation Network and is generously sponsored by the Cognizant Foundation with additional support from Intel, Microsoft, and Western Governors University. This brief was prepared by Kristin Baddour, a policy analyst at the NGA Center for Best Practices, and Katherine Ash, consulting director of the NGA Workforce Innovation Network.