This issue brief was created to help governors implement a multidisciplinary strategy to prevent targeted violence. This brief distills the latest research and draws from elements of public-health interventions to provide guidance to governors, state and local leaders, and other stakeholders on how to prevent ideologically-inspired violence.

Executive Summary

The Issue

Ideologically-inspired violence—whether political, ideological, gender-based, or religious can disrupt communities and impact the health, safety, and well-being of children, families, and other vulnerable populations, social services, education, public health, and civil rights officials.

The Approach

Preventing targeted violence requires a coalition of stakeholders that extends beyond a state’s law enforcement agency. The intersectional nature of the threat necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to identify the root cause of violence and mitigate it from spreading. The principles of public health provide a useful framework for addressing this issue.

Role of Governors

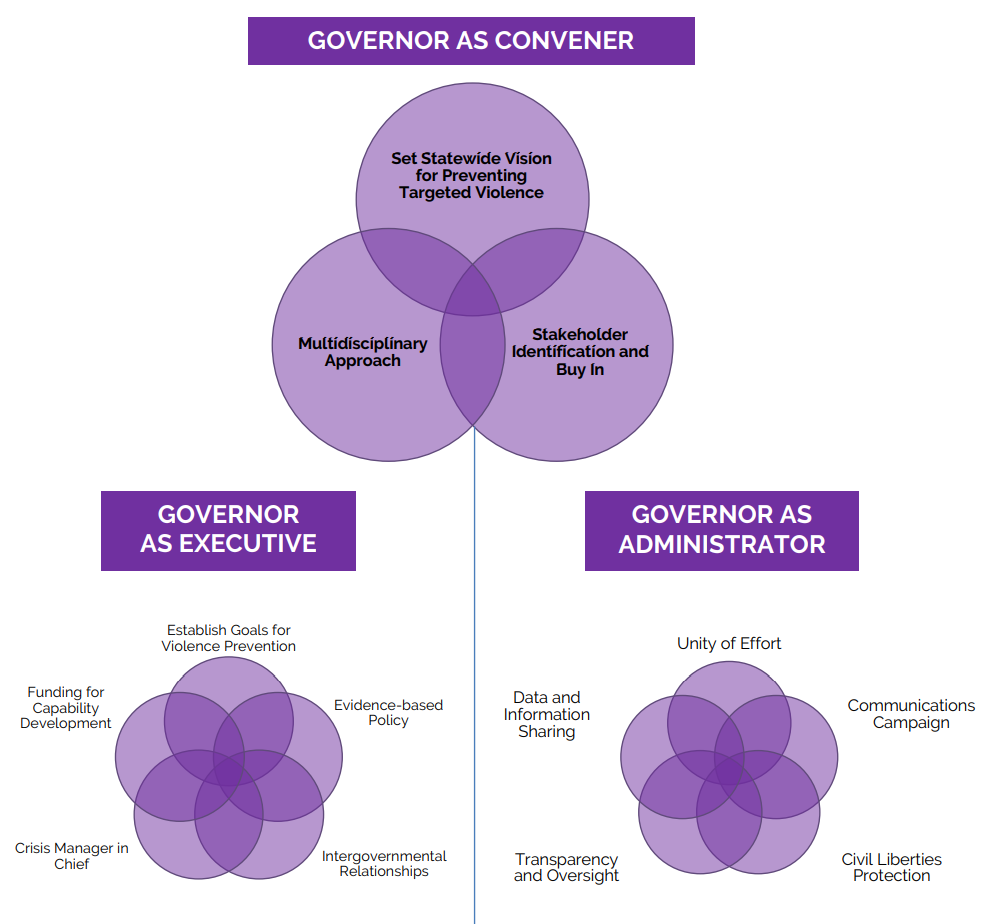

In addressing the threat of targeted violence, governors play an important role in setting the vision for their state, engaging stakeholders, and developing a comprehensive strategic plan.

This role may best be understood by examining lessons from leadership in times of crisis, recent events across the nation, and best practices from practitioners from social services, public health, civil rights, and law enforcement. As well as an examination of what can be done to prevent motivations toward violence, strengthen the social fabric of communities, and intervene when the threat of violence became imminent.

The Issue Brief

The Preventing Targeted

Violence Issue Brief was created to help governors implement a multidisciplinary strategy to prevent targeted violence. This brief distills the latest research and draws from elements of public-health interventions to provide guidance to governors, state and local leaders, and other stakeholders on how to prevent ideologically-inspired violence—whether political, ideological, gender-based, or religious. By taking a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach to preventing such violence, states can build safer and more resilient communities.

The brief is a subsect of “A Governor’s Roadmap to Preventing Targeted Violence” which is based on more than 80 interviews with subject matter experts (SMEs), conclusions drawn from NGA Center’s Policy Academy on Preventing Targeted Violence, two SME roundtables and practitioner research.

For additional information about the

issue brief, please contact Carl Amritt at camritt@nga.org.

Governor’s Leadership

Given their roles and responsibilities, governors have constitutional and statutory roles in ensuring the safety and wellbeing of all who live in their states. Protecting their citizens from targeted attacks is one of their most important duties. Many governors begin this process by examining recent tragedies within their states, searching for opportunities to mitigate motivations to violence, strengthen the social fabric, and prevent future attacks.

Governors have a unique convening power that can be leveraged to develop broad stakeholder buy-in for a statewide vision on targeted violence prevention. They can connect key multidisciplinary leaders from state agencies, local partners, and non-governmental organizations to obtain commitment and set strategy. As chief executives, governors establish goals for preventing targeted violence and prioritize prevention capability development through budgeting, executive orders, and

other gubernatorial tools.

As regulators and administrators, governors can increase collaboration of executive branch agencies within their states, including law enforcement, human services, and public health and ensure transparency and oversight for any violence prevention program. They can coordinate the lines of work between state, local, and community-based organizations, ensuring a cohesive, specific, intergovernmental approach.

BEST PRACTICE: Leverage the governor’s role as convener, executive, and administrator at key points in implementing targeted violence prevention, including strategy setting, program design, and securing community support.

Background

What is Violent Extremism?

“Violent extremism” is not a federally defined crime and individuals cannot be charged as “violent extremists.” As such, prosecutors rely on a series of federal and state statutes to charge individuals with related crimes. However, various federal frameworks delimit the contours of how violent extremism may be defined.

“A Person Of Any Citizenship Who Has Lived And/Or Operated Primarily In The United States Or Its Territories Who Advocates, Is Engaged In, Or Is Preparing To Engage In Ideologically-Motivated Terrorist Activities (Including Providing Support To Terrorism) In Furtherance Of Political Or Social Objectives.”

DEFINING “HOMEGROWN VIOLENT EXTREMISTS”

The 2016 White House’s “Strategic Implementation Plan for Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the U.S.,” defines “CVE” as: “Proactive actions to counter efforts by extremists to recruit, radicalize, and mobilize followers to violence.”

The definition was broadened in 2019 Department of Homeland Security’s “Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targeted Violence.”

This brief adopts the terminology “targeted violence,” rather than “countering violent extremism,” or “CVE,” to encompass all premeditated acts of ideologically-inspired violence targeting specific populations. Since 9/11, usage of the term “CVE” has come to be associated with interventions understood as anti-Muslim and targeting populations based on their religious beliefs.

As such, we use “preventing targeted violence,” or “PTV,” to refer to a new approach focused on preventing violence rather than what may have motivated that violence. This approach can promote greater awareness among stakeholders about the various, evolving motivations behind such violence and help dispel the misconceptions that only al-Qaeda or ISIS-inspired individuals are motivated to such acts of violence.

How is Violent Extremism Defined Under Federal Law?

Under national security laws, however, acts of targeted violence may be defined as acts of terrorism. Under the Antiterrorism Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 2331-2339D, “international terrorism” as activities that involve violent acts or acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State, or that would be a criminal violation if committed within the jurisdiction of the United States or of any State; Appear to be intended to: 1) To intimidate or coerce a civilian population; 2) To influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or 3) To affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and occur primarily outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States, or transcend national boundaries in terms of the means by which they are accomplished, the persons they appear intended to intimidate or coerce, or the locale in which their perpetrators operate or see asylum.

These specific statutes do not carry criminal charges but can be applied to associated statutes when charging a suspect with a

criminal act. Such charges include Use/Attempted Use of a Weapon of Mass Destruction (18 United States Code [U.S.C.] § 2332a)

and Providing Material Support to Terrorists (18 U.S.C. § 2339A). To date, however, those who have met the definition of “domestic terrorism” have not been charged with a terrorism-related crime.

Acts of targeted violence are also addressed in hate-crime statutes. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 (18 U.S.C. § 249) carries a criminal penalty and defines “hate crimes” as offenses involving actual or perceived race, color, religion, or national origin. Whoever, whether or not acting under color of law, willfully causes bodily injury to any person or, through the use of fire, a firearm, a dangerous weapon, or an explosive or incendiary device, attempts to cause bodily injury to any person, because of the actual or perceived race, color, religion, or national origin of any person and offenses involving actual or perceived religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.

Several states, however, have codified targeted violence statutes in their state codes. Because of the number of such federal and state statutes, state, local and federal prosecutors typically work together to determine which federal or state charges to bring in a case.

Integrating Public Health

A goal of a Preventing Targeted Violence (PTV) approach is to illuminate why targeted violence is more than simply a law enforcement matter. The multidisciplinary nature of the threat necessitates a multidisciplinary approach to ensure the root cause of violence is identified and prevented from spreading.

The PTV model presented here draws on public-health interventions is based on a public health approach: collective action by behavioral health (mental health and substance misuse), public health, and law enforcement practitioners. As such, it includes primary, secondary and tertiary prevention efforts:

PRIMARY PREVENTION

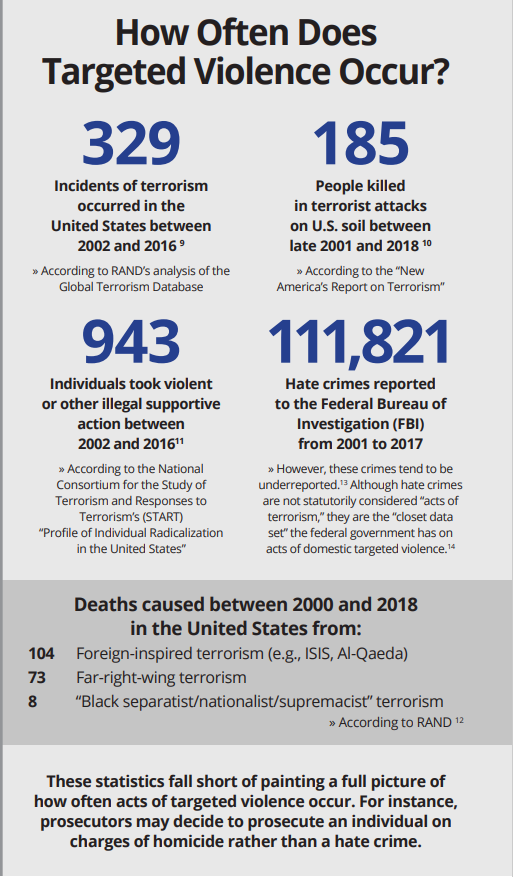

Primary prevention efforts in the public health domain include an array of activities aimed at preventing disease before it occurs, such as risk mitigation and resiliency strategies. For PTV, states would need to start their engagement and primary prevent approaches by informing local stakeholders — mayors, social service providers, public health staff, educators, chiefs of police — about how frequently or infrequently targeted violence occurs in the state. PTV also includes identifying and explaining the root causes of targeted violence to policymakers and practitioners based on solid research and data.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

These efforts typically refer to actions directed at a specific population that is susceptible to a disease or is in the early stages of experiencing a disease. With respect to PTV, secondary prevention means helping those who may be prone to risk factors or may already be experiencing or exhibiting the risk factors have not, or are not at imminent risk of, committing targeted violence.

TERTIARY PREVENTION

These efforts focus on curing an individual of a disease or preventing relapse. This roadmap is not focused on “curing” someone of an ideology. Rather, it emphasizes relapse prevention strategies. For example, mitigating risk of further targeted violence through specific interventions to individuals who have committed an act of targeted violence and may be reengaging with the community (e.g. through release from prison).

Why Violence Prevention?

PARTNERSHIPS: PTV maps on to other prevention and mitigation efforts, such as public health approaches, creating natural synergies and partnership opportunities across multiple disciplines.

CIVIL RIGHTS AND LIBERTIES: PTV assumes that the problem is violence and behavior surrounding a targeted approach to violence, not what could be legally protected speech, ideology or religion. Focusing on violence rather than ideology helps safeguard civil rights, civil liberties and privacy, and it lessens the potential for targeting constitutionally protected ideologies or beliefs.

SUPPORT LOCALS: States can play a key role in supporting, scaling and spreading promising local interventions through sharing resources, fostering relationship, and bringing training and technical assistance to local efforts that need it. They have greater access to resources than their local counterparts and can foster relationships through local and national programs.

COORDINATION: A state-led approach can drive coordination with local government entities and nonprofit organizations.

STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT: A PTV approach promotes the

inclusion of stakeholders across disciplines by delineating roles and responsibilities among them while encouraging collective action.

Steps to Preventing Targeted Violence

1. Establishing Governance and Strategy

A statewide PTV strategy is critical for creating and sustaining buy-in for programs and policies. Effective implementation of a PTV strategy requires engagement from multiple agencies, levels of government and public-private partnerships, rather than operating solely through law enforcement.

2. Data

To understand the full impact of acts of targeted violence, leaders must collect and analyze relevant data from targeted violence within their state. By understanding the scale and scope of the threat, state leaders can develop a more targeted strategy.

3. Developing Evaluation Metrics

Establishing evaluation metrics is important to validate the methods of your state targeted violence program and allows for replicability across other states. It is important to have standard and uniform definitions across states to describe and measure state targeted violence efforts to prevent against insufficient metrics, inadequate transparency on outcomes, and lack of scientific rigor.

4. Creating a Sustained Community Partnership Model

Whether states in early phases of creating a PTV program or with robust programs in place, educating stakeholders and the public about targeted violence and the roles they play in PTV is important. States must strengthen relationships with key constituencies, provide transparency into governmental activities and articulate how the program can protect and balance civil rights, civil liberties and privacy.

5. Enhancing Current Violence Prevention Programs

Several state, local, nonprofit and private organizations operate violence prevention programs in cities and counties. Rather than building separate, distinct programs, states may be more successful with their PTV strategy if they integrate their efforts with existing programs.

6. Connecting Individuals with Resources

To counteract targeted violence, states can utilize tertiary prevention mechanisms to prevent the spread of or relapse into violence. One way to accomplish this is by reengaging an individual with the community through referral systems — locally

and at the state level.

7. Disengaging from Violence

Tertiary prevention efforts should occur in state and local correctional facilities for those convicted of a targeted-violence crime (e.g., terrorism-related crimes; hate crime; crimes committed to further an ideology, belief or religion) or who exhibit risk factors that may mobilize them toward violence upon release. States could review their current in-prison programs, those that support reentry or other post-release programs to determine how they could be used for targeted-violence offenders.

Acknowledgements

Authors

- Lauren Stienstra, Former Program Director, Homeland Security, NGA Center for Best Practices

- Carl Amritt, Senior Policy Analyst, Homeland Security, NGA Center for Best Practices

The National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) thanks the U.S. Department of Homeland Security for its support of this publication.

The authors also thank Jeff McLeod for editorial review and guidance, and former NGA staff who have substantially contributed including Michael Garcia and Alisha Powell.

The authors appreciate the valuable insights from: Eric Rosand, Prevention Project: Organizing Against Violent Extremism.