Learning and Employment Record Use Cases

Skills-based hiring has spread rapidly in the past two years—with no fewer than 10 states dropping degree requirements for most government jobs. And many large employers have made similar moves.

LERs are hot. What are states going to do with them?

Governors and state leaders are concerned about the current labor shortage, occurring during a time when many skilled workers are underemployed or even unemployed. Skills-based approaches to hiring and recruiting can shift that dynamic—making pathways to good careers accessible to a wider segment of the workforce and opening up new pools of talent for employers. They do so by focusing on what workers know and can do, not on the degrees or credentials they’ve earned.

That’s the theory. But a lot hinges on how things actually play out on the ground.

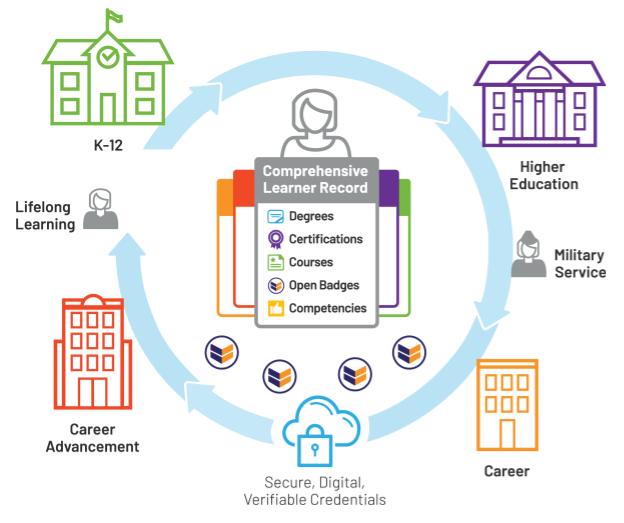

Technology will play a key role, and many states have zeroed in on learning and employment records—essentially digital resumes with verified records of people’s skills, educational experiences, and work histories—as an essential tool. A lot of important work is going into the technical design and specifications.

This project, on the other hand, aims to take a step back and look at the current state of play when it comes to the use cases for LERs. Just a few of the key questions:

- How might employers, education providers, government agencies, and workers themselves actually use them? Will they?

- In what areas do state policymakers have the most influence over key stakeholders and the most responsibility to invest?

- What actions are needed now to ensure that LERs, and skills-based hiring more broadly, actually widen access to good jobs—rather than setting up a parallel system that perpetuates many of today’s inequities?

These are enormous questions, and the National Governors Association has engaged trusted education/workforce journalist Paul Fain to examine these issues through a journalistic lens, with a focus on the practical realities on the ground rather than theory. We will focus heavily on the moves that states and other key actors are already making—and whether they are seeing early wins or learning hard lessons. The goal is both to provoke deeper thought about what it really means for states to invest in LERs and to shed light on uses that have the most immediate potential to shift workforce dynamics, invigorate local economies, and change lives.

If you would like to learn more about NGA’s work in the skills/LER space- please reach out to Program Director Amanda Winters at awinters@nga.org

Resources

Building a Skills-Based Talent Marketplace, Jobs for the Future (JFF)

In a skills-based talent marketplace, jobseekers have the tools to more effectively share their skills, work experiences, and learning qualifications with potential employers, and hiring managers identify applicants who are able to succeed in jobs they’re trying to fill, whether or not they have traditional credentials, like a four-year college degree. This JFF market scan focuses on a technology solution that enables this transformed talent marketplace: digital wallets where learners and workers can store and share the artifacts of their achievements and share their skills as they pursue opportunities for advancement.

LER Resource Hub, US Chamber Foundation

The Learning and Employment Records Hub by T3 Innovation Network provides a variety of resources to support organizations implementing LERs as well as a community for learning and sharing best practices.

Interoperable Learning and Employment Records – Competency-Based Education Network (C-BEN)

C-BEN compiled a common set of principles for education and employment data for use by key decision makers who provide education and training to millions of Americans each year, including policy makers, state and federal agencies, philanthropy, employers, colleges and universities, K-12 district leaders, workforce agencies, and military branches.

Early Wins: A Tailored Tool for a Big Problem

By Elyse Ashburn and Paul Fain

Policymakers and technologists who are working to build learning and employment records talk about the ways they could transform how people navigate education and work—supercharging competency-based education, skills-based hiring, and new pathways into “good jobs.”

It’s the holy grail of data infrastructure and seen as the fuel for systems change. But while some states are inching closer to that reality, it’s still a long game.

Enter the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, which is helping states score early wins with a new tool named CLIFF. It underlines the potential of even tailored solutions to tackle big problems.

In this case, the problem is how so-called benefits cliffs can restrict work and career advancement. CLIFF sounds approachable, but feeds on a complex array of data on job growth, income projections, state policies, and federal benefits formulas. It’s designed to help both lower-income individuals and employers better understand how government benefits—and ultimately well-being—are impacted as people earn more and advance in their careers.

“In one sense it’s really just a career exploration tool,” says Alexander Ruder, director and principal adviser on the Atlanta Fed’s Community and Economic Development team. “We want tools that can help workers plan and meet their financial goals.”

For now, CLIFF mostly works on the “employment” side of the LER equation, but it’s already influencing action in a number of states—an example of how even discrete tools that stop short of a fully-realized LER can have an impact on policy and lives, by giving people data to make better-informed choices.

The tool also reflects a growing recognition that our education and workforce systems don’t operate in a vacuum. Social policy on health, transportation, childcare, and other arenas plays a major role in who enters and succeeds in those systems.

Connecticut, for example, has tapped CLIFF as part of the state’s 2Gen Initiative, which focuses on putting both parents and kids, the next generation, on a path to economic stability. Case managers use the tool directly with individuals, and state leaders have used its backend data to model the impact of policy change and to begin exploring new approaches to helping families manage benefits cliffs.

The state has provided guidance to Maine, Kentucky, and Alabama as they pursue similar work. In Alabama, the tool is being incorporated into the state’s new Talent Marketplace—arguably the country’s most fully-realized example of a skills data system and LERs in action.

The Need for States

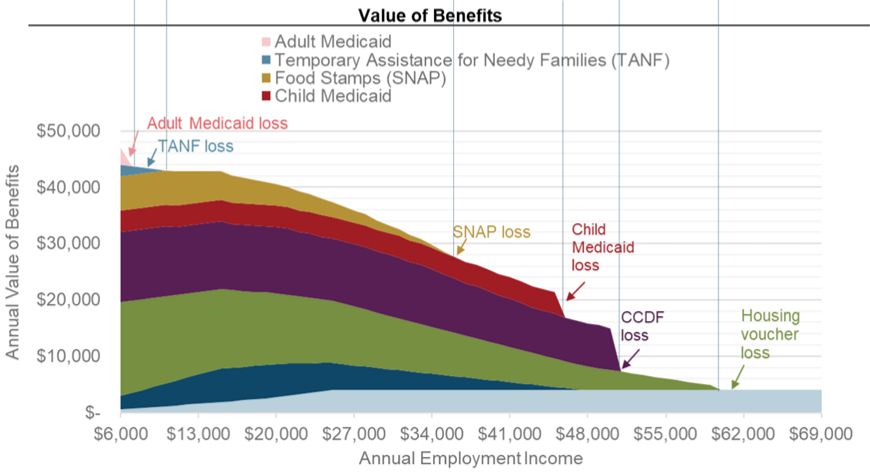

Benefits cliffs have long bedeviled both state policymakers interested in self-sufficiency and economic growth and case workers as they try to help unemployed and low-income workers move up. The cliffs are points where even a small increase in income can lead to a large decrease in—or even a wholesale loss of—particular federal benefits.

Childcare subsidies are a particularly problematic one. The Atlanta Fed modeled, for example, that “Leia,” a single mother of two in Miami earning just under $50K a year, will suddenly lose childcare benefits if her income goes above that threshold—such that a $1K increase in income will leave her with a new $7K bill. And she’s already been losing Medicaid and other benefits along the way. The net effect is that Leia is about as well off earning $51K a year as she was earning $7K.

Benefits cliffs have been studied for decades. But before the Atlanta Fed’s work there was no real-time model for showing how they would impact people career-by-career.

“We started to model out career paths that looked really good on paper and looked really good by earnings, but once you start to map out benefits loss, they don’t look so good,” Ruder says. “People were really shocked that career paths that they thought would be a win-win for everyone would actually be a loss for their workers.”

One such pathway—training to be a certified nursing assistant and then a licensed practical nurse—typically comes highly recommended. It’s a common path for single mothers and other low-income women. The career arc looks good at first blush, but when you factor in benefit loss, it can take 15 years before someone following the LPN path actually has more financial resources than someone just working a minimum wage job. That’s half a working career, or almost an entire childhood.

Better data tools can’t change that, but they can inform policy changes that would. In the current labor market environment, many states are eager to increase workforce participation and upskilling. And at least a third of states have taken recent legislative action to address benefits cliffs in some way.

The CLIFF tool also is designed to help businesses and other employers understand how what they see as a good thing—a modest raise—can actually leave an employee worse off for years. In Leia’s case, she’d have to get to about $65K in annual income before she’d be doing as well as she was when she was making $50K. Similar impacts are at play when hourly workers are given raises or asked to increase their hours.

The tool aims to help employers think about compensation more creatively, perhaps offering transit passes or health care coverage that may qualify for special tax treatment and not trigger benefits loss.

Moreover, CLIFF offers employers a rare view into how career paths actually look and feel from their workers’ perspective.

On the Ground

The CLIFF tool for case workers and individuals is already helping people in Maine think differently. They can’t erase benefits cliffs, but they can help people refine their training and career plans, better prepare for the cliffs, and reduce fear, says Serena Powell, executive director of Fedcap Maine, which the state contracts to provide case management and career support for Mainers on public assistance.

“We think it’s very useful,” she says. “And DHHS wants us to use it.”

Maine first piloted CLIFF last year, and plans to roll it out more broadly in the coming year. Results from the pilot study showed that before using the dashboard, 81% of participants somewhat or strongly agreed it was possible to become financially self-sufficient within the next five years. After using it, that increased to 98%.

Powell points to an example of what that looks like in someone’s real life.

One of Fedcap Maine’s caseworkers had been working with the same client for years. The woman had training and work experience as a certified nursing assistant, but also disabilities that impacted her ability to work. She had been receiving benefits from the state’s Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program for more than eight years, and was determined to qualify for another federal program for individuals with disabilities that would potentially provide benefits for life.

It was a lengthy process, and far from a guarantee—a reality her caseworker had been talking her through for months and months.

Then, the caseworker and client sat down with the CLIFF tool. It was like a light bulb went off, says Powell.

There, in a tidy graph drawn out for decades, it showed that if the woman stayed on federal benefits, she’d never be more than scraping by. The same was mostly true if she went back to work as a CNA, but the trend lines for her looked different if she could train up quickly to be a licensed practical nurse or, even better, a registered nurse.

There’d be cliffs along the way—but the tool gave the woman more certainty about where they’d be and for how long. The picture was specific to her situation. In the span of the session, her goal shifted to finding an employer who would provide accommodations that enabled her to work full-time and quickly train to advance.

“It’s just such a mindshift,” Powell says. “She could see it in a new way.”

States and the Infrastructure of Opportunity

By Paul Fain and Elyse Ashburn

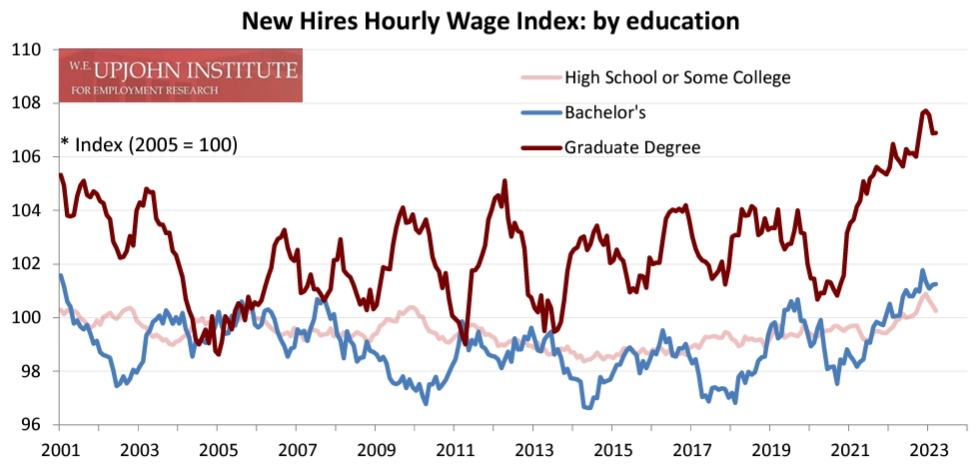

The skills-first revolution is in full swing, as a growing number of states and big companies are dropping degree requirements and trying to hire based on skills.

The shift is about equity and the bottom line. Employers are struggling to retain and hire workers amid rapid technological changes. Policymakers want to boost economic development while opening doors for workers who have long been left behind. And schools and colleges are feeling more pressure to better prepare students for the evolving labor market.

Yet despite all the enthusiasm for skills-based systems, research shows that no progress has been made to increase job opportunities for Americans without college degrees. It’s a chicken-or-the-egg dilemma—moving beyond the four-year degree as a proxy for skills is hard if people can’t otherwise signal to employers what they know and can do. The best ways to do that remain bullet points on a PDF of a résumé and letter grades on a paper transcript.

Many efforts are underway to create the language and technology to capture skills. But that work so far has failed to really move the needle, in part because it’s largely happened in silos. Even the terms for these tools differ depending on who is using them. An educator might talk about a badge or comprehensive learner record while an employer refers to a digital wallet or learning-and-employment record (LER).

We’re nowhere near a world where a worker controls a verifiable, clear record of their skills, and can use this tool as they move between jobs, education, and training. Many experts are dubious this scenario will become a reality in the next decade or two. But ambitious projects to develop data infrastructures around skills are happening now. And the stakes are high.

The Learning Economy Foundation equates this challenge to the development of plumbing standards in the United States. A century ago, widely divergent plumbing practices and often conflicting codes among cities and states drove up construction costs and contributed to public health crises.

The arrival of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) piping revolutionized plumbing, says Taylor Kendal, president of the Learning Economy Foundation. And the technology’s rapid spread helped drive more coordination on plumbing standards.

The development and widespread adoption of some version of a programmable, verifiable credential, or PVC, could contribute to a similar sea change with skills, Kendall says. There is an urgency to make this a reality , thanks to employers feeling the pinch around the skills gaps and the severe enrollment crisis that’s buffeting higher education.

The work to watch most closely, according to many experts, may be efforts by states to create datasets and tools to help people to bridge education and employment. That’s partially because state policymakers see the skills conundrum from multiple angles, which creates bipartisan momentum for change.

“The social imperatives are aligned with the employment imperatives,” says Deborah Everhart, the chief strategy officer at Credential Engine, a nonprofit focused on mapping credentials.

If state agencies develop workable data that can help direct and drive investment in training programs in high-demand fields, the skills-based revolution could live up to the hype.

“We’re in an interesting era,” says Kendall. “The world’s changed a lot.”

Connecting Education and Training with the Labor Market

In the past two years, 12 states have dropped degree requirements for the majority of state government jobs. They’ve been struggling to fill key roles in cyber, IT, and administration—and to expand opportunities for residents in historically low-income ZIP codes. At the same time, K-12 school districts and daycares can’t hire or retain enough teachers, and hospitals, doctor’s offices, and other healthcare providers are desperate for more medical assistants and nurses. In states, like Alabama, where education levels have historically lagged and lots of new employers are moving in, skilled labor shortages are acute across the board.

Virtually every state is grappling with how to improve benefits and employment systems, which were exposed as severely lacking during the pandemic. States struggled to get unemployment money in the hands of millions of newly-laid off workers, and it was almost impossible to get real-time information on market conditions and to target job-search support and training to those who needed it most.

“We cannot afford to wait for the next crisis to improve our systems,” says Robert Asaro-Angelo, commissioner of the N.J. Department of Labor and Workforce Development.

Several states are betting that learning and employment records can be a key piece of the puzzle. They come at it in different ways, but all have made major investments in statewide longitudinal data systems, starting more than 20 years ago and with major grant support from the federal government. Those systems thus far have mostly been used to inform research, policy making, and agency actions—but could serve as the backbone for LERs.

About half the states are participating in Credential Engine’s registry, which aims to create a centralized repository of education credentials and the basic competencies they indicate. New Jersey, for example, is starting to take advantage of the major advances in big data, machine-learning, and AI to make connections between the training programs in the registry and the skills that are in demand in the state’s labor market.

Twenty-eight states have invested a collective $3.8 billion in short-term credentials that are focused on getting workers skills for in-demand jobs. Some of that investment dates back to the early 2000s, but the vast majority has come in the past five years. Louisiana’s M.J. Foster Promise Program, which is designed to target high-need residents, and Virginia’s New Economy Workforce Credential pay-for-performance grant, are standout examples, according to a recent analysis by HCM Strategists.

Minnesota sets the gold standard for tracking outcomes in short-term credentials—a key consideration if states are hoping to use skills data to make recommendations to workers about upskilling and reskilling programs.

Other states, Illinois and Alabama chief among them, have focused heavily on mapping employability skills and the competencies—knowledge, skills, and career-relevant behaviors—that underpin education programs and jobs. Illinois has encouraged colleges to move to competency-based education, which enables people to receive credit for knowledge learned on the job, in fields like early childhood education that face severe worker shortages and also have strict education and licensing requirements.

A few states, including Arkansas, have gone as far as testing out fully functional LERs and marketplaces for skills-based training and job matching.

Yet perhaps no state is further along than Alabama, which has launched a skills marketplace, starting with manufacturing and healthcare industries, and plans to expand to more industries this fall. Its experience is illustrative of the common thread in all these seemingly disparate efforts—connecting data systems, investing in short-term credentials, tracking outcomes, encouraging competency-based education and skills-based hiring. In fact, Gov. Kay Ivey’s mandate is that all of this has to connect.

Alabama is five years into its work, and expects at least four more of sustained work. Having a long-tenured governor and the political will to look beyond easy wins is key, says John Pallasch, a workforce consultant and former assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Labor.

“It’s not as if the government for the past 200 years hasn’t been doing anything and there is a ton of low-hanging fruit just waiting there,” he says.

To start, Alabama brought together a host of state agencies and regional leadership to identify high-demand, high-pay roles across 16 different industry sectors and to begin breaking them down into core competencies. That ongoing work then informed a push for competency-based education in many college programs, especially in the community college sector. And the competency framework and accompanying data became the basis for the skills-based jobs marketplace that is now live.

As that marketplace grows, learning recommendations will be layered in, along with information on state and federal benefits. The marketplace, for example, plans to incorporate a new tool from the Atlanta Federal Reserve Board that models how wage gains might impact an individual’s eligibility for federal benefits.

In that way, the work reaches across education, labor, commerce, and health and human services.

“Bringing together a cross-sector of Alabama stakeholders to focus with intentionality on braiding their data systems is essential to understanding and responding to the needs of our workforce,” says Chandra Scott, CEO of Alabama Possible. “This is how gaps in services and supports can be identified to ensure a pathway for upward mobility is available to under-resourced students and workers across our state.”

After all, learning and employer records are a discrete tool, requiring investments in data, technology, and governance. But they really aren’t anything more than a digital artifact if the culture, employer practices, and funding and incentive systems around them don’t change. It’s the same way that a college diploma is just a piece of paper—if not for all the ways businesses and society have internalized and codified its meaning over generations.

Focus on Incentives for Colleges

A lot of energy in Texas has focused on changing college incentives. Gov. Greg Abbott just signed off on a new funding formula for community colleges that will for the first time give them regular funds for short-term programs.

Mike Flores, chancellor of Alamo Colleges, says having a dependable source of funding—not a one-time grant or a pilot program—will allow short-term credentials to reach the kind of scale that’s needed to have an impact in the labor market.

“This is a dedicated revenue source that Alamo and the 49 other community colleges within the state can rely on to really upskill our workers within our community,” he told Work Shift.

Even private sector efforts have focused heavily on college incentives. GreenLight Credentials, based in Dallas, was an early entrant into the LER market. When ITT Technical Institutes collapsed in 2016, Dallas College took on the management of many of its student records as part of the wind down. The chancellor at the time went looking for a technical solution that would allow the students to own their records directly, and GreenLight grew out of that effort.

Today, it operates a blockchain solution for 120 school districts and dozens of colleges in the Dallas area and across the state. A main selling point is easier transcripting processes for colleges and 24-hour access for students, says Shrikant Jannu, GreenLight’s chief platform officer.

But colleges increasingly are using it as an enrollment tool—targeting students for admissions offers and scholarships based on the information they’ve shared through their digital wallets, or “lockers.” That could be a major incentive for colleges to welcome LERs, as they look to widen their applicant pool and combat declining enrollment.

“It’s interesting that a school can apply for a student,” says Sheri Thoman, head of digital marketing at GreenLight. “It just flips the whole script.”

Signal in the Noise

A strong consensus among many experts holds that employers are the key to whether a broad shift to skills-based systems happens in the next decade. In a market-based economy, the demand side of the equation is the driver of change.

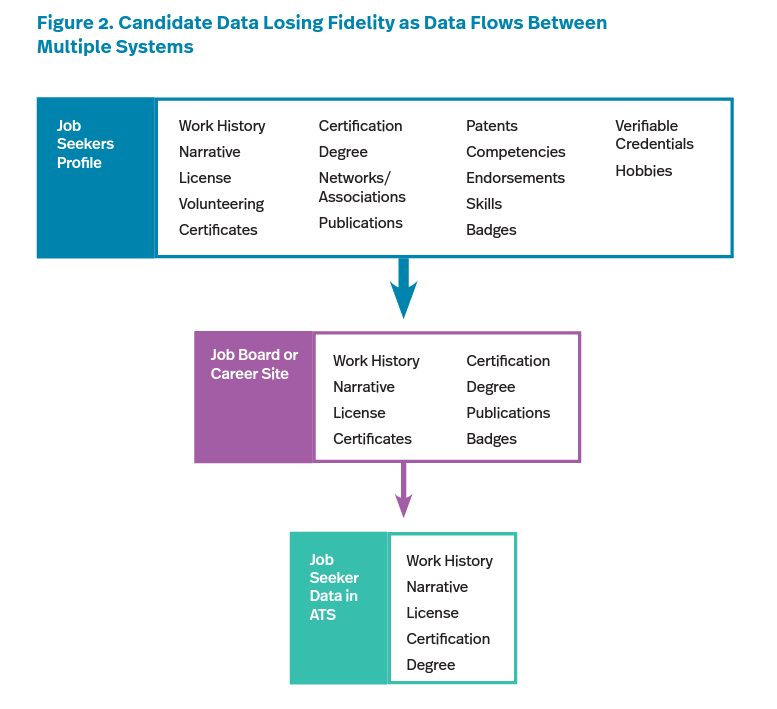

As it stands, most corporate HR departments are not equipped to collect good data about the skills of jobseekers, or even to accept digital credentials, according to a recent analysis conducted by Northeastern University’s Center for the Future of Higher Education and Talent Strategy. Instead, researchers at the center and 1EdTech found that HR systems still primarily record basic information about degrees and resumes.

“The skills infrastructure and architecture isn’t there yet,” says Sean Gallagher, the center’s executive director.

The top reason HR tech providers say they aren’t doing more to capture digital credentials or structured skills data is that most of their customers aren’t calling for it. Yet this may be changing, slowly. More employers will accept digital credentials and see digital wallets among consumers over the next 5-10 years, predicts an executive at an HR tech firm. “It’ll be a hockey stick adoption curve,” he told researchers from the center. “But we’re on the bottom of the stick right now.”

In the meantime, a growing number of big companies appear to be getting serious about skills as they try to operationalize their pledges to drop degree requirements.

Medtronic, for example, has replaced requirements for bachelor’s degrees with skills across fully half of its IT job roles. The medical device company, which employs 95K workers, has tapped its education benefit program partner, InStride, to help “recredential” or map out the skills for 65 roles across 17 job families, from entry-level to senior roles.

For new hires, this means Medtronic can do skills-based recruiting and hiring. And the skills mapping can help open doors for the company’s frontline workers who are interested in promotions to midlevel roles where degrees may not be necessary. “We’re still early on, with some significant progress,” says Amy Wilson, the company’s director of global talent acquisition programs and employment brand.

Businesses collect plenty of data on jobs and employment, and are required to report much of it to state and federal agencies. Yet that information fails to give a clear picture of what’s going on in the labor market, or about the skills of workers.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation has been working for more than five years to find a signal in the noise with better, standardized data. The Foundation’s Jobs and Employment Data Exchange (JEDx) promotes the creation and widespread adoption of standards for jobs and employment records. JEDx includes incentives for businesses to participate voluntarily, in part by making it easier for them to securely organize, share, and report data that’s already required under government regulations.

“Everybody benefits if we can make the labor market more efficient and effective and easier to navigate,” says Jason A. Tyszko, vice president of the Center for Education and Workforce at the U.S. Chamber Foundation.

Some version of skills mapping is crucial for companies to make good on their pledges to diversify and to open doors for more Americans, including those without college degrees. Any attempt to move toward skills-first talent management is a major internal lift for businesses, and lots of organizations are trying to help them do it, says Elyse Rosenblum, managing director and co-founder of Grads of Life, which advises large employers on this work.

“For any of this to get to scale, companies have to understand, is it good for business?” says Rosenblum.

As employers and states develop skills-based infrastructures, some vendors in the LER space are counting on the emergence of a bottom-up data standard—one not developed by a big company or imposed by the federal government—to allow for interoperability across industries and state borders.

Territorium, for example, is banking on the Comprehensive Learner Record Standard from 1EdTech. The standard draws from previous work around open badges, is compatible with the Credential Engine registry, and has been endorsed by the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers.

“We’re going to build to the standard,” says Jonell Sanchez, who until recently was chief growth officer for Territorium, a skills platform which has had broad success with LERs in Latin America and is seeking to expand in the U.S. He says the solution from 1EdTech may have the best odds of creating an alternative currency for skills “that will have some street cred.”

A more prescriptive set of standards won’t work in this country, Sanchez predicts. And that’s not a bad thing.

“We’re never going to have a national answer,” he says. “It’s going to be different in Minnesota than in Pennsylvania.”