There is no silver bullet for the mental health crisis but reducing workforce shortages of these critical providers can go a long way to solving the problem.

by Jessica Kirchner & Isabella Cuneo

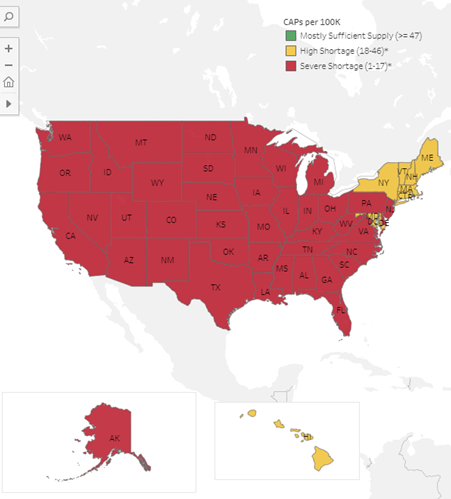

For the past decade, the prevalence of mental illness and the need for highly skilled providers have been steadily rising, and incidence rates of depression, anxiety, loneliness and suicidality have soared, especially among children. Leading pediatric health experts are declaring a national child and adolescent mental health emergency exacerbated by the simultaneous increase in demand and lack of access to care. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, nearly 1 in 5 children experience a mental health issue, but only about 20% receive care. As shown in the map below, shortages in mental health providers are a national trend. Striving for a robust mental health workforce, Governors and their state agencies have developed targeted plans and strategies to recruit and retain mental health providers. These plans and strategies can address state needs both during times of crisis and beyond the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised unique opportunities for Governors to reform mental health service delivery. A robust mental health workforce is a critical factor in the provision of necessary treatment and care for children facing mental health challenges and is key to combatting the growing provider shortage. Complicated problems require creative solutions, and many states have adopted innovative tools to address these shortages. These state tools include:

- Tool 1: Align curriculum between 2-year community colleges and 4-year colleges to guarantee seamless credit transfer for mental health-related degrees, such as social work and psychology; and

- Tool 2: Offer creative incentives to offset the higher cost of programs requiring certifications and/or higher education and to attract workers into high-demand fields, such as social work; and

- Tool 3: Adapt apprenticeship models to support the social services and mental health workforce to create mental health provider pathways that provide valuable experience for students, lessen the financial burden of education and provide support to existing full-time social workers

Tool 1: Aligning curriculum between 2-year community colleges and 4-year colleges

When the curricula of community colleges and 4-year colleges are incongruent, it can hinder students’ ability to move from an associate degree to a bachelor’s degree. A community college student majoring in social work may not realize that some required coursework is irrelevant or incompatible with the requirements of a 4-year college, and the extra time and financial cost of marrying the disparate requirements can be a huge deterrent from entering the field.

States, such as Massachusetts, have successfully established curriculum alignment for other high-demand fields. Massachusetts created a Memorandum of Agreement with 15 community colleges that established the Massachusetts Workforce Development Consortium to address the shortage of clinical nursing assistants. The consortium aims to work with statewide agencies and educational institutions to create an information-sharing network so that the curricula of community colleges are aligned with those of other institutions. Modeling this practice with an Associate of Social Work and Bachelor of Social Work degrees could better support seamless transitions between institutions, thereby greasing the wheels for students to enter the field through community colleges and experience fewer disruptions on their path to full accreditation.

Tool 2: Offering Creative Incentives

Most states currently operate a loan repayment program funded by grants from the U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). These loan repayment programs can help states to attract more students into the mental health field with the promise of debt repayment backed by the federal government. Each state uniquely designs its own programs and can structure them to bolster the recruitment of new mental health providers.

Michigan’s loan repayment program is structured to recruit and retain high-demand clinical social workers and Mental Health Counselors. In Michigan, a mental health provider would be able to receive one of the highest loan assistance amounts in the country – up to $300,000 over ten years. The provider could participate in the loan repayment program for almost a decade – enough time to put down roots in a new community. Michigan’s loan repayment program touts the highest number of providers participating in the program in the nation in 2021.

Michigan’s program:

- Offers up to $200,000 per provider over the course of ten years for participating in the program

- Tailors repayment plans based on provider’s loan debt

- Funded by 40% federal, 40% state, and 20% employer dollars: federal dollars are drawn down from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s loan repayment grant, and state contributions are designated in Michigan’s general fund

Alaska’s healthcare leaders recognized an opportunity to expand upon its existing federal partnership loan repayment program by leveraging the support of local providers and community organizations. Alaska created an additional state support-for-service incentive program to attract a larger practitioner pool to address a wide range of practitioner occupations and positions. Alaska’s program offers two types of benefits: education loan repayments and/or a direct incentive. Mental health practitioners who have been in the workforce for several years may no longer carry student loan debt and therefore may not be incentivized by loan repayment programs, despite the value that their experience can bring to rural communities. Because Alaska’s state-run program allows providers to receive a direct incentive, more tenured providers have reason to enroll in the program. The numbers speak for themselves: Alaska’s programs currently serve 515 mental health providers with enrollment rates increasing each year.

Alaska’s state-run program:

- Recruits more health providers that are excluded from HRSA funding because of debt level, licensure, specialty or region

- Can be administered as student-loan repayment or a direct incentive payment

- Blends funding from a myriad of sources: federal grants, for-profit partners, nonprofits and trade associations

Tool 3: Adapting Apprenticeship Models

Apprenticeships have long been used to create a seamless pathway for workers to expand their skills through compensated hands-on experience. In the past, these opportunities existed primarily in trade-based industries, but some states have pioneered the adaptation of successful apprenticeship models into pathways for mental health professionals. The opportunity for students to participate in a paid or financed apprenticeship program while earning critical credentials eases the financial burden that might deter potential providers from pursuing such an opportunity.

Nebraska is taking collaborative, community-based steps to assuage the mental health provider shortage, including establishing a designated Behavioral Health Education Center focused on recruiting, retaining and increasing the competency of the state’s behavioral health workforce. Nebraska’s state officials chose to embrace the philosophy that there is no one strategy to tackle the provider shortage, but rather a whole-system framework is necessary to work collaboratively across state departments and collectively to address this multi-faceted issue. Nebraska has established multiple programs in partnership with state agencies and community-based organizations to maintain a robust behavioral health workforce.

Nebraska’s model:

- Exposes high school students to the field through the Frontier Area Rural Mental Health Camp and Ambassador Program, enlisting students early into a pipeline while promoting rural job recruitment and retention

- Connects high school students to behavioral health professionals through the state’s Virtual Mentor Network, providing individualized mentorship opportunities with professionals who are in psychiatry or psychology fields

- Advances the capacity of individuals who serve young children, including, teachers, law enforcement officers, attorneys, mental health professionals, local primary care physicians, and others to handle child mental health concerns in their communities through free or low-cost Infant Early Childhood Mental Health training

With support from Governor Kay Ivey, Alabama launched a registered apprenticeship program as a way for Alabama A&M students seeking a master’s in social sork to attain critical credentials. This new program is one of the first in the country to model a traditional apprenticeship design for mental health professionals. The Alabama Office of Apprenticeship credits its innovative program to Governor Ivey’s leadership, to its strong partnership with Alabama A&M and to the flexibility afforded from the autonomy of having a state-led apprenticeship approval process. The apprenticeship program is designed to meet specific employer needs and leverage public- and private-sector resources.

Alabama’s program:

- Provides licensing and certificates upon completion of master’s in social work degree (Targeted Case Management Certificate from the Alabama Department of Mental Health and Board Licensure)

- Partners with local health businesses and employers to determine the accuracy of demand for both providers and necessary credentials

- Subsidizes the cost of apprenticeships with resources from private sector employers who benefit from increased providers

Conclusion

There is no silver bullet for the mental health crisis but reducing workforce shortages of these critical providers can go a long way to solving the problem. Without access to mental health providers, children struggling with mental health issues are left without treatment and at risk of experiencing long-term health issues. As the nation has learned over the past few years, complex problems require creative solutions, and these states’ unique solutions offer a promising path forward.

To be connected with any of the states mentioned above, please reach out to the Children and Families Policy Analyst, Belle Cuneo at icuneo@nga.org. You can find additional resources on Human Services issues at our website here.