By the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health and NGA

H.R. 1 created the Rural Health Transformation Program, offering states an opportunity to reimagine rural health care systems through a $50 billion federal investment. This is an opportunity for Governors to improve mothers’ mental health significantly and, therefore, family well-being in their states’ rural communities.

Background

Maternal Mental Health

Maternal mental health disorders impact 20% of women, while those living in rural communities are 21% more likely to face perinatal depression compared to women living in urban communities. These disparities are driven by various factors exacerbated by social drivers of health. For example socioeconomic challenges (e.g., poverty, unemployment and food insecurity) compounded by limited access to behavioral health specialists, stigma and fragmented systems of care can negatively impact a mothers’ wellness. Untreated maternal depression can lead to poor short and long-term intergenerational outcomes. Related outcomes can include higher rates of pre-term and low birth weight deliveries, long-term health and mental health risks for both mother and child. In the mother, untreated maternal depression can increase her risk of suicide, chronic depression, substance use and poor health, including obesity.

Due to the impaired early attachment to a caregiver, children also experience poor outcomes, including higher rates of behavioral challenges, cognitive deficits, and mental and physical health issues in their lifetimes. These conditions can lead to chronic struggle to which rural populations are most exposed.

Maternal Substance Use

Substance use during pregnancy and postpartum introduces additional challenges. For example, pregnant women living in rural communities have greater rates of past-month tobacco use, with rates continuing to increase over time. Maternal tobacco use is linked to serious short- and long-term consequences for children, including low birth weight, reduced brain development, impaired heart rate variability in utero, and later risks of obesity and cognitive delays.

While national data show no major rural–urban differences in the odds of binge drinking or illicit drug use among pregnant women, rural residents face significantly greater barriers to treatment access. Rural peripartum women with opioid use disorder (OUD) are less likely to receive medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) compared to their urban counterparts, and rural hospitals are less likely to offer addiction consults or OUD medications in emergency or inpatient settings. Additionally, higher provider stigma and limited addiction training in rural areas further restrict access to care.

Impact of Maternity Care and Mental Health Deserts

The closure of hospital labor and delivery units in rural communities continuously impact access to care and create dangerous care deserts. Due to decreasing practicing obstetricians, over half of U.S. counties do not have a hospital that provides obstetric care. With nearly half of American counties operating without a practicing Ob/Gyn, research reflects that limited access to an obstetric provider is linked to increased poor health outcomes including maternal mental health disorders.

Further, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health’s 2025 U.S. Maternal Mental Health Risk & Resources Report highlights maternal mental health provider shortage areas by county, compared to the population’s risk for a maternal mental health disorder. Severe workforce shortages of perinatal mental health certified (PMH-C) providers, reproductive psychiatrists, and community-based organizations providing maternal mental health services are especially pronounced in rural and frontier regions.

Opportunities to Strengthen Rural Health

These challenges present a unique opportunity to improve outcomes for women and their children by advancing policy, technological and infrastructure solutions.

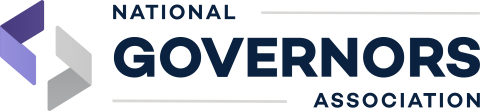

Developing Diverse Workforces

States can promote, develop, and/or refine existing community college training programs for obstetric and mental health providers who live and will work in rural communities. Examples include: Blue Ridge Technical College, a community college in West Virginia, offers a certificate in addiction counseling, and Cerro Coso Community College in rural Kern County developed an associate of science degree for licensed midwives, clinicians who provide prenatal, labor and delivery, and postpartum care. States can provide financial aid, such as loan repayment or tuition waiver programs, to increase rural healthcare workforce recruitment and retention rates.

Encouraging Home and Mobile Care

States can incentivize providers serving non-rural communities to travel weekly to rural communities to provide care in patients’ homes, or via mobile units such as a car, van, bus or even a tiny home. Obstetric and mental health providers are not restricted to offices, as “place of service bounds” restrictions do not apply to outpatient benefits delivered by individual providers. Providers can bill Medicaid and private insurance using the address where services were provided and place of service (POS) code 99.

Using Technology & Telehealth Consultation

States can address telehealth via expanding internet/broadband access, creating state telepsychiatry consultation (primary care and obstetrics consulting with psychiatrists), and covering digital therapeutics at no charge to patients. These approaches allow expecting and postpartum mothers to receive timely care from trusted providers while overcoming distance and stigma barriers. States can also explore innovative resources, including supporting behavioral health providers’ use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to streamline medical record notetaking, and adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) and submission of electronic claims.

Engaging Healthcare Payors

Payors, including state medical agencies (SMAs), can play a pivotal role in improving detection and follow-up for maternal mental health conditions by requiring reporting of HEDIS perinatal depression screening and follow-up measures. Evidence-based strategies include requiring managed care contracts to address screening and detection by obstetric providers and requiring health insurers and health plans to provide maternal health case management to ensure women and their families find timely in-network treatment. Health plans and SMAs can incentivize strong screening and follow-up outcomes through pay-for-performance and shared savings reimbursement strategies.

Accountability and Outcomes

To ensure measurable progress and measurement-based care, states could establish clear benchmarks for insurers and Medicaid health plans for maternal and behavioral health outcomes, such as maternal mental health screening and treatment rates, and reduced postpartum emergency room visits, readmissions and deaths. Health plans that meet defined benchmarks could maintain or expand funding in subsequent years, while those that fall short could receive targeted technical assistance to strengthen implementation. This outcome-driven structure will help ensure that public investments deliver tangible improvements in maternal mental health and rural health system performance.

Pilot Regional Maternity Care Centers (MCCs) in Obstetric Deserts

The Federal Maternal Mental Health Task Force recommends that the government pilot the creation of Maternity Care Centers (MCCs) in obstetric deserts, where labor and delivery hospital services and obstetric outpatient services do not exist. The thinking is that just as fire departments, libraries and schools are critical infrastructure, so is maternity care. In 2009, Georgia developed six Regional Perinatal Centers (RPCs), funded by the Georgia Department of Public Health, to provide needed maternal, fetal, neonatal and infant care in communities with gaps left by shuttered hospitals. However, a recent report highlights “the ongoing need for increased resources, particularly in rural areas.” States can use transformation funds to pilot MCCs modeled after Georgia’s RPC program or the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) model, delivering critical obstetric and behavioral health services in the same facility. MCCs can offer comprehensive support, including postpartum home visiting, dyadic mother-baby classes and support groups, parenting and infant development classes for both mothers and fathers, and support with practical needs when warranted.

Ongoing Support is Available

For more information on how Governors can improve maternal mental health through the Rural Health Transformation Program, contact Marianne Gibson: mgibson@nga.org or Joy Burkhard at joy.burkhard@policycentermmh.org.