Preventing and mitigating adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress and promoting resilience are increasingly priorities for Governors. To mount an effective response to ACEs, states may consider a holistic approach to promoting resilience for children and their families and adopt approaches that combine universal training, access to screening and treatment, improved data collection and reporting, and also a commitment to transformative, cross-agency cultural change.

(Download)

Executive Summary

Experiencing adversity early in life can affect a person’s health, well-being, and success into adulthood. A groundbreaking study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente, released in 1998, found that adults who experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), ranging from physical and emotional abuse, and neglect to various forms of household dysfunction, in sufficient duration and intensity, had significantly elevated risk of heart disease, diabetes, substance use disorder, smoking, poor academic achievement, and early death. COVID-19 has brought additional attention to the impact of ACEs and trauma across the lifespan, which may be exacerbated by disruption in the lives of families; increased family stressors; income, food, and housing insecurity; social isolation; and school closures.

Recognizing the critical role that Governors and their staff can play in implementing policies that can prevent and mitigate ACEs, the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, in partnership with the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy and the National Academy for State Health Policy, conducted an intensive, multi-state technical assistance project on statewide approaches to address ACEs across the lifespan, starting in June 2020. Across the work with the selected five states, the following areas of focus emerged:

- Establishing trauma-informed states by creating a holistic, cross-agency vision for cultural change;

- Developing a common, statewide language and lens around trauma and ACEs and implementing universal trauma awareness communications and/or training;

- Improving the quality of ACEs surveillance data; and

- Increasing access to ACEs screening and developing a comprehensive, trauma-informed system of care.

As a capstone of this project, this paper highlights lessons learned from states that served as models for statewide approaches that prevent and address ACEs and the development of trauma-informed policies (Alaska, California, New Jersey, and Tennessee). The paper also addresses the goals, policy, and programs developed and launched by states that were selected for the project (Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wyoming).

BACKGROUND

About ACEs

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include experiences such as physical and emotional abuse and neglect, caregiver mental illness, and household violence. Higher exposure to ACEs has been linked with an increased risk for heart disease, diabetes, poor academic achievement, smoking, substance abuse, and even early death. COVID-19 and the declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health has brought additional attention to the impact of ACEs and trauma across the lifespan. COVID-19 has created disruption in the lives of families; increased family stressors; worsened income, food, and housing insecurity; increased social isolation; and limited identification of needs and access to services and supports due to school closures.

Approximately 61 percent of adults have experienced at least one ACE and 16 percent have experienced four or more. ACEs are common across sociodemographic groups; however, they do not impact all sociodemographic subgroups equally. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that Black, Latinx, female, and lower income individuals on average experience more ACEs that White, male, and higher income individuals respectively. States, including those participating in the learning collaborative project, are increasingly identifying ACEs and trauma as an important locus for addressing health equity.

In addition to personal outcomes, ACEs carry a significant economic burden, including for state governments. For example, a 2019 analysis by the Sycamore Institute found that ACEs among adults in Tennessee led to an estimated $5.2 billion in direct medical costs and lost productivity. A 2020 evaluation by the California Surgeon General’s office identified the health-related costs of ACEs and toxic stress to the state at $112.5 billion annually.

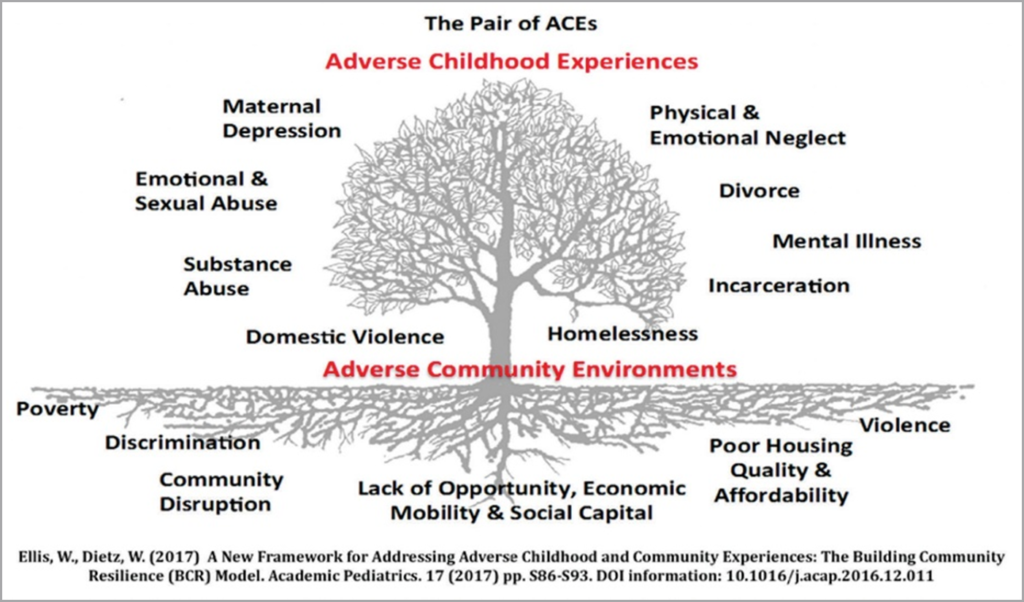

Toxic Stress and Building Resilience

Exposure to ACEs alone does not guarantee that an individual will experience heart disease, diabetes, poor academic achievement, smoking, substance abuse, or early death and some children without significant ACEs may experience some of these outcomes. ACEs interact with preexisting biological and genetic factors as well as with resilience and supportive factors to precipitate health and social outcomes. As demonstrated in Figure 1, ACEs are experienced in combination with environmental and social factors which may contribute to or mitigate health and social outcomes and serve as an opportunity for intervention, referred to as the Building Community Resilience Model.

Typically, experiencing adversity triggers stress response systems in a child’s developing brain. Excessive activation of these systems over time can lead to “toxic stress,” particularly in the absence of protective factors that foster resiliency. Toxic stress can disrupt brain development and lead to social and emotional challenges later in life. Interventions focus on preventing ACEs in the first place, building resilience, and mitigating possible health and social outcomes that may be associated with ACEs. Direct interventions can include fostering strong relationships between children and supportive adults, building life skills across the lifespan, meeting the basic needs of families, incorporating trauma informed practice into service and supports, and providing access to health, behavioral health, and social services.

STATE STRATEGIES TO PREVENT AND MITIGATE ACES

I. Establishing a cross-agency vision for cultural change

Cross-sector and cross-agency work is important for aligning policies and resources at the state level to target ACEs interventions, from prevention to mitigation. A number of states are addressing ACEs by

combatting siloed and disconnected work, including through executive orders, to build a statewide vision and direct state agencies to prioritize addressing ACEs and through the establishment of cross-agency teams, work groups, and offices to coordinate ACEs and trauma work.

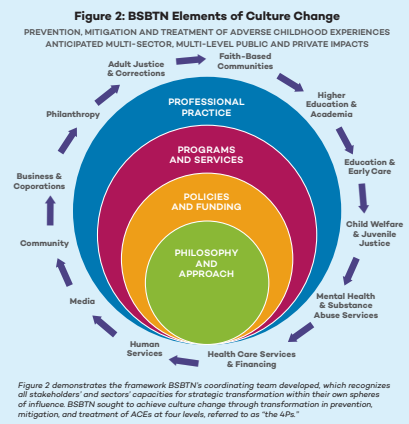

Building Strong Brains Tennessee is a national model for statewide culture change, governance, and public-private partnerships. Building Strong Brains is jointly led by the executive, legislative and judicial branches of state government and mobilizes knowledge derived from the science of brain development and communication science, often referred to by Tennessee as a three- branch, two-science approach. Tennessee sought to achieve culture change across all sectors and across all levels of government and community, emphasizing the importance of taking ownership over an individual or group’s own sphere of influence (Figure 2). Building Strong Brains credits much of its success to its governance and infrastructure, which relied on the leadership in the three branches of government and its robust partnerships across public and private sectors, and grew out of participating in NGA’s and the National Conference for State Legislature’s Three Branch Institute. The various stakeholders met independently and jointly to guide the work on ACEs and trauma informed care in the state. For more information on the Tennessee’s model, please see A Case Study of Building Strong Brains Tennessee: An Initiative to Address Adverse Childhood Experiences and Become a Trauma-Informed State.

New Jersey created an Office of Resilience in June 2020, funded through philanthropic organizations and in partnership with the New Jersey Department of Children and Families. The office is a statewide home for state agencies and community-led efforts focused on eradicating ACEs, offering technical assistance, and providing strategic support. The Office of Resilience, in partnership with the New Jersey ACEs Collaborative and the Department of Children and Families, released the NJ ACEs Statewide Action Plan in 2021, which identifies five key strategies to reduce and prevent ACEs in New Jersey: 1) Achieve trauma- informed and healing-centered state designation; 2) Conduct an ACEs public awareness and mobilization campaign; 3) Maintain community-driven policy and funding priorities; 4) Provide cross-sector ACEs training; and 5) Promote trauma-informed/healing-centered services and supports. The state also formed an ACEs Interagency Team, coordinated by the Office of Resilience, comprised of agency decision-makers, which meets monthly and is tasked with plan implementation. Following the release of the action plan, the Office of Resilience is supervising the development of a technical assistance resource center that will support implementation of efforts related to the action plan. New Jersey’s Office of Resilience served as a model for many of the states participating in the learning collaborative project.

In Delaware, Governor John Carney signed Executive Order 24 in October 2018, declaring the state trauma-informed. The Family Services Cabinet Council, tasked with implementing this order, conducted a landscape analysis by interviewing the leads of each individual child and family-serving agency to determine to what extent they were already incorporating trauma-informed practices into their work. These interviews helped form the cross-agency vision of the Trauma-Informed Delaware action plan. As of 2021, Family Services Cabinet Council agencies meet to discuss cross-agency ACEs and trauma priorities every month. A number of initiatives have emerged from these meetings, including an ACEs messaging campaign based on The Number Story and questions around trauma-informed practices and self-care being added to an annual survey circulated to all state employees. Delaware is using the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale to assess state employees’ attitudes and changes over time as the state becomes trauma-informed.

In June 2018, Governor Ralph Northam of Virginia signed Executive Order 11, establishing the Children’s Cabinet and outlining three main priority areas of focus, among them a direction to “support a consistent, evidence-based, and culturally-competent statewide response to childhood trauma,” and directing agencies to foster systems that provide a consistent trauma-informed response to children who have experienced trauma and build resiliency of individuals and communities. The Governor’s Trauma-Informed Leadership Team, a state-level steering committee comprised of leadership from Virginia’s child, youth, and family-serving state government agencies, meets regularly to discuss cross-agency priorities around trauma, and to identify recommendations for legislative and budgetary changes. In the summer and fall 2020, the Governor’s Trauma-Informed Leadership Team held a series of meetings on developing a cross- system strategy for preventing and alleviating COVID-19 related traumas. External experts and agency leadership presented on best practices and current commonwealth initiatives, resulting in the development of a report enumerating considerations for preventing and mitigating ACEs during the pandemic that was presented to First Lady Northam and the Commonwealth Children’s Cabinet in October 2020.

In Pennsylvania, Governor Tom Wolf signed Executive Order 2019-05 in July 2019, establishing the Commonwealth as a trauma-informed state and creating the Office of Advocacy and Reform to serve as the central coordinating body to implement the executive order. The Office of Advocacy and Reform created a think tank of experts from fields including psychology, psychiatry, domestic violence counseling, and population health. The think tank worked to establish definitions for terms like “trauma-informed care” and “healing-centered practices,” as well as determine a set of values and core principles for action and planning. This resulted in the Trauma-Informed PA Plan, which was approved by the Governor and launched in July 2020. In October 2020, HEAL PA (Healing Empowerment Advocacy Learning Prevention Action) was formed as a public-private coalition to implement the plan across sectors and disciplines, through its 14 action teams that meet monthly and the bi-monthly leadership team. The coalition has about 150 diverse members and is critical both for gathering input and ensuring sustainable, cross-sector implementation. Coalition members represent community-based organizations, behavioral health providers, people with lived experience, foundations, educators, county government, academia, and state child and family serving agencies. Most recently, Governor Wolf also directed the Office of Advocacy and Reform to prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion, and HEAL PA has prioritized preventing and mitigating racist violence and radicalization in the Commonwealth, beginning by learning from experts on preventing and mitigating radicalization.

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan signed an executive order on May 6, 2021, directing state agencies to consider how their policies and programs could reduce ACEs, share necessary data to study and monitor ACEs, and implement care models informed by ACEs. In addition, the executive order declared May 6th as ACEs Awareness Day annually and directed all state units to coordinate to reduce ACEs across the state. Finally, Governor Hogan concurrently announced $25 million from the CARES Act as part of the Coronavirus Emergency Supplemental Funding program for Project Bounce Back to help Maryland youth recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Project Bounce Back will include public-private partnerships to expand mental health crisis services, youth development programs, and digital solutions. Maryland has a history of supporting cross-system partnerships to support children and families including through their Children’s Cabinet and Local Management Boards. Anne Arundel county is an example of a county which leveraged funds from the Governor’s Office for Children and the Children’s Cabinet to build collective impact around addressing poverty and other environmental stressors for children and their families.

Resources for cross-agency cultural change

Statewide Plans

- Trauma-Informed Pennsylvania: A Plan to Make Pennsylvania a Trauma-Informed, Healing-Centered State

- New Jersey ACES Statewide Action Plan

- Delaware Family Services Cabinet Council Trauma-Informed Care Progress Report and Action Plan

- Considerations for the Virginia Children’s Cabinet: Preventing and Mitigating Adverse Childhood Experiences Related to COVID-19

- A Case Study of Building Strong Brains Tennessee: An Initiative to Address Adverse Childhood Experiences and Become a Trauma-Informed State

Executive Orders

- Delaware Executive Order 24 Making Delaware a Trauma-Informed State

- Pennsylvania Executive Order 2019-05 Protection of Vulnerable Populations

- Maryland Executive Order 01.01.2021.06 Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Executive Order Number 11 (2018) The Way Ahead For Virginia’s Children: Establishing The Children’s Cabinet

Internal planning and analysis documents

- Virginia HEALS Agency Trauma-Informed Self-Assessment Tool

- Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale

II. Developing a common lens around trauma and ACEs and implementing universal trauma awareness training

For many states, a first step in determining a path forward for preventing and mitigating ACEs is developing a consolidated, statewide language and framework for discussing ACEs and their impact on later life outcomes, as well as articulating and disseminating principles for trauma-informed care.

Tennessee grounds its Building Strong Brains Tennessee public-private partnership for reducing the effects of ACEs, in a two-sciences approach that leverages brain science and communications science. Building Strong Brains Tennessee, in partnership with the Frameworks Institute, developed a common language on the neurobiology of trauma and its impact on child development through convenings of state and government officials, community leaders, academics, and other stakeholders. Once this common language and understanding was developed, the Building Strong Brains partnership implemented widespread training on the effects of ACEs and trauma for people from diverse professional disciplines and sectors. To date, 80,000 people, including more than 7,000 educators and administrators, have been trained.

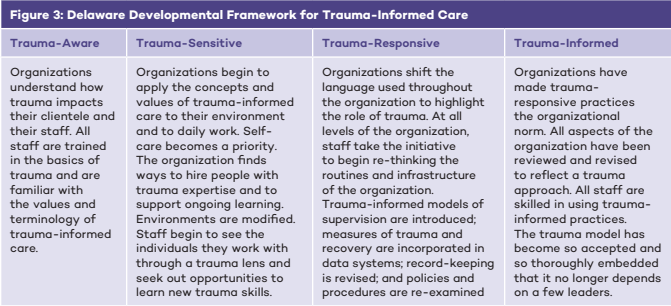

In Delaware, following the 2018 Executive Order declaring the state trauma-informed, the state’s Family Services Cabinet Council produced the Delaware Developmental Framework for Trauma-Informed Care in 2019. The framework, which was adapted from the state of Missouri’s model for trauma-informed care, outlines foundational principles for trauma-informed care, as well as benchmarks and indicators for what it means for an agency to become trauma-informed (see Figure 3). Using this framework as a guide, the state worked to implement universal trauma awareness training for state employees. As of 2020, every Family Services Cabinet Council secretary and their leadership teams have been trained in foundational trauma-informed care principles, along with thousands of front-line staff. Furthermore, the state has held events to honor trauma awareness month each May since 2019, including a kick-off symposium at Delaware State University at which more than 300 Delawareans were educated on the effects of trauma. The state is also currently working to develop an internal agency communications campaign to provide ongoing education to all state employees on the significance of ACEs to their work. This campaign uses Number Story, a national public education campaign launched by the ACEs Resource Network, as its basis.

Pennsylvania, through input from HEAL PA and the internal team working on ACEs, is now taking the stance that every child in Pennsylvania has at least one ACE and therefore is creating a Universal Healing Strategy. Training on trauma-informed practices is core to implementing this strategy with commonwealth employees and employees of all licensed, contracted, and funded commonwealth entities. The Office of Advocacy and Reform requested $4.2 million as part of the American Rescue Plan Act state recovery funds that Pennsylvania is receiving for their trauma-informed plan goals and ACEs strategy and also embedded trauma and resilience into other agencies’ ARPA requests where there is overlap (i.e., behavioral health).

In Virginia, Governor Northam’s Trauma-Informed Care Working Group was tasked with fulfilling directives in the 2018 Appropriations Act and Executive Order 11, aimed to create a system of trauma-informed care. In an effort to align the many state agencies, non-profits, and private service providers moving towards becoming trauma-informed, the working group recommended that Virginia’s child and family-serving programs and agencies adopt the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration framework for defining trauma-informed care and services in the behavioral health sector, in hopes that other child and family serving sectors such as child welfare, education, criminal and juvenile justice, primary health care, the courts, and housing would adapt the definition within their systems.

Resources for ACEs training and building a common language

- Delaware Developmental Framework for Trauma-Informed Care

- The Missouri Model: A Developmental Framework for Trauma-Informed Approaches

- Finding your Frame: Translating the Science of Early Adversity for Action Presentation from Frameworks Institute for the Tennessee ACEs Symposium

- Tennessee Case for Action: Addressing Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Tennessee Strategy for Using Evidence-Based Communication to Advance Public Understanding

- Tennessee Public Service Announcement Episodes on Adverse Childhood Experiences as a Public Health Issue

III. Improving the quality of ACEs surveillance data

To effectively develop strategies on ACEs prevention and mitigation, states are interested in better understanding the scale and nature of the problem. A number of states have pursued innovative strategies for improving ACEs data collection and reporting.

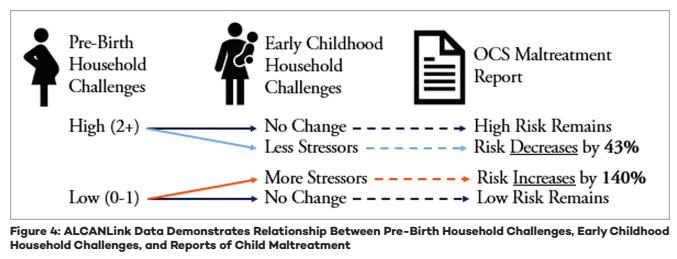

Alaska introduced the Alaska Longitudinal Child Abuse and Neglect Linkage Project (ALCANLink) in 2017. The project is a mixed-design strategy that links the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data, which monitors maternal attitudes and behaviors before, during, and after pregnancy, with several administrative data sources, to identify families at high risk of child welfare involvement and elevated ACEs in early childhood. The data are being used by the state to develop a clinical decision-making tool for providers to use during the pre-birth pregnancy period to screen and calculate risk, facilitate diagnosis in the context of protections, and refer families to services, if needed, with the goal of preventing ACEs.

Current research and models produced using ALCANLink data demonstrate that household challenges, such as mental illness, a relative who is incarcerated, a mother who was treated violently, substance abuse, and divorce, pre-birth increased risk of contact with child welfare and average childhood ACEs scores. Alaska’s most recent analysis (Figure 3) found that children born into households that transitioned from facing a higher number of household challenges during the pre-birth period to facing substantially fewer household challenges during early childhood experienced reduced risk of child maltreatment. Mirroring this relationship, if a household went from experiencing few pre-birth household stressors during the pre-birth period to a higher number of stressors during early childhood, the child’s risk for maltreatment increased substantially. Respondents whose households continuously faced fewer or no household challenges during both time periods did not significantly change their already low risk for being reported for child maltreatment. These findings suggest that child maltreatment prevention efforts focused on minimizing household challenges should begin before birth, and resources and prevention programs should remain actively available to families throughout childhood.

Alaska used ALCANLink results, among other sources, to make the case to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for a Section 1115 demonstration that provides community-based early intervention services to children and adolescents who have experienced 4 or more ACEs. For more information, see the provider services manual. Alaska is the first state with a demonstration through which individuals are able to qualify for services based on having experienced ACEs.

To better understand the effects of ACEs in Wyoming, the state incorporated ACEs related questions into the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and are analyzing the data for release. Pennsylvania is also working to improve data quality around ACEs and trauma. In 2021, the Office of Advocacy and Reform collaborated with the Department of Education to introduce ACEs-related survey questions to the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. The commonwealth has also worked to share Pennsylvania Youth Survey data on ACEs risk and resilience factors with members of the HEAL PA public-private coalition.

Finally, over the course of 2021, Maryland developed a cross-agency ACEs data work group, with the goal of creating an integrated system to identify and track ACEs exposure, including eventually through a statewide data dashboard. The work group has created an ACEs data inventory and needs assessment, met individually with all child and family-serving agencies to determine what data is currently available, and is currently in the process of determining indicators to be included in a public dashboard.

Resources for ACEs data collection

- Introducing the Alaska Longitudinal Child Abuse and Neglect Linkage Project (ALCANLink)

- Rittman, D., Parrish, J., Lanier, P. November 2020. Prebirth Household Challenges To Predict Adverse Childhood Experiences Score by Age 3. Pediatrics 146 (5)

- Alaska Substance Use Disorder and Behavioral Health Section 1115 Demonstration

- Alaska Behavioral Health Providers Services Standards & Administrative Procedures for Behavioral Health Providers Manual

- States Collecting ACEs Data Through the BRFSS

IV. Increasing access to ACEs screening and developing a comprehensive, trauma-informed system of care

To quickly identify and respond to ACEs and childhood trauma, states are broadening access to ACEs screening, as well as developing robust referral and response protocols and trauma-informed networks of care.

As part of its ACEs Aware initiative, California covers screening of ACEs under Medicaid for children and adolescents using the Pediatric ACEs Screening and Related Life-events Screener (PEARLS) and for adults using the ACE Questionnaire for Adults. Beginning in January 2020, the California Office of the Surgeon General and California’s Medicaid agency began offering providers no-cost training on trauma and trauma-informed care through the ACEs Aware website. The 2-hour online course includes information on: 1) The California Department of Health Care Services policies and requirements for providers to receive reimbursement for screening; 2) How to screen for ACEs using the Pediatric ACEs and Related Life-Events Screener (PEARLS) and ACEs tools; 3) Training on ACEs Screening Clinical Algorithms to assess patient risk of toxic stress physiology; 4) Science of trauma; and 5) How to implement trauma-informed care.

The California Surgeon General’s Office, state , California Medicaid, and other stakeholders also created a Trauma-Informed Network of Care Roadmap: A Guide for Strengthening Community Relationships to provide practical steps health care providers, clinics, community-based organizations, and social service agencies can take to grow cross-sector Networks of Care within their communities. They also awarded $33 million in ACEs Aware grant funding to 35 organizations across California to build and strengthen trauma-informed networks of care, that support Medicaid providers, social service systems, and community partners to effectively respond to ACEs and toxic stress through community-based health and social supports. For more information on the ACEs Aware initiative, please see A Case Study of California’s ACEs Aware Initiative.

Wyoming, with consultation from the California ACEs Aware team, received approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services and is planning to open Medicaid reimbursement for ACEs screening for children and adults in 2021. The California Office of the Surgeon General is partnering with Wyoming to provide training to Wyoming providers. Simultaneously, Wyoming is pursuing system of care strategies to best support children across the continuum of needs in order to prevent serious crises and to provide adequate treatment to children in need.

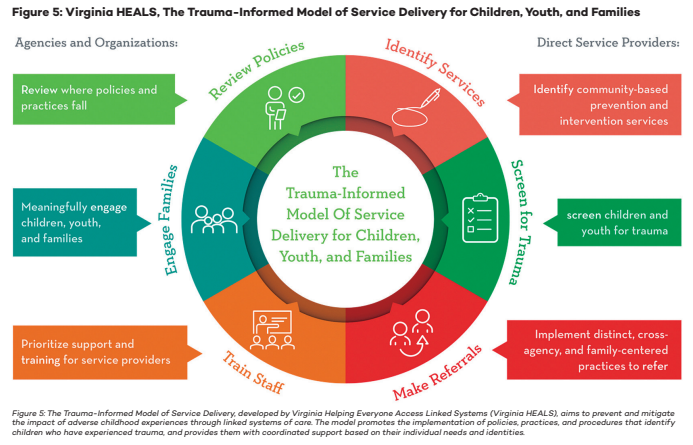

Virginia’s Trauma Informed Model of Service Delivery (Figure 4), developed by Virginia HEALS (Helping Everyone Access Linked Services), is designed to promote healing for children and youth that have experienced trauma. This model was originally part of the Linking Systems of Care for Children and Youth statewide demonstration initiative, supported by the United States Department of Justice.3 The model includes the Screening for Experiences and Strengths questionnaire, a screening tool for identifying trauma and victimization experiences and symptoms in children and youth, as well as a Referral and Response Protocol, Community Resource Mapping Guide, and an Agency Self-Assessment intended to help train local agencies, organizations, and communities, and build capacity for and goals around trauma-informed care and service delivery. Virginia also supports 19 local Trauma-Informed Community Networks. These networks play a diverse range of roles in their communities including building awareness of trauma and ACEs, conducting training and supporting the implementation of new, trauma-informed practices in schools, courts and community services. The state’s 2021 special session resulted in targeting $1 million of American Rescue Plan Act funding for the community networks. The funding is to be used to develop a community-driven trauma awareness campaign in which communities with the greatest need are identified and provided grants to help build or build back their networks, prevent ACEs, and promote resiliency. The budget also included $600,000 for the Virginia Mental Health Access Plan program to expand trauma-responsive care education to primary care providers, particularly pediatricians.

States have also worked to strengthen their trauma-informed systems of care by developing organizational assessments and criteria for determining if a site is practicing trauma-informed care principles. Pennsylvania’s Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services created a survey that was sent to child psychiatric residential treatment facilities in the commonwealth to identify their level of trauma-awareness. The office evaluated survey results and provided individualized technical assistance to facilities based on their identified level of trauma awareness. This survey was also sent to non-psychiatric residential facilities for children and youth, as well as the commonwealth’s Office of Children, Youth and Families.

Resources for screening and developing a trauma-informed system of care

Screening

- California ACEs Screening Tools

- California ACEs Aware Training Resources

- Case Study of California’s ACEs Aware Initiative

- Virginia HEALS Screening for Experiences and Strengths Training

- Virginia HEALS Referral and Response Protocol

Trauma-informed systems of care

- California ACEs Aware Trauma-Informed Network of Care Roadmap

- Virginia HEALS Community Resource Mapping Facilitation Guide

- Virginia HEALS Agency Trauma-Informed Self-Assessment Tool

- Pennsylvania Residential Treatment Facility Trauma Informed Care Implementation Survey

- Tennessee Building a Trauma Informed System of Care Toolkit

CONCLUSION

Preventing and mitigating adverse childhood experiences and toxic stress and promoting resilience are increasingly priorities for states. To mount an effective response to ACEs, states may consider a holistic approach to promoting resilience for children and their families and adopt approaches that combine universal training, access to screening and treatment, improved data collection and reporting, and also a commitment to transformative, cross-agency cultural change. Significant momentum was created during the NGA and National Academy for State Health Policy learning collaborative project, which has since led to a group of seven mid-Atlantic states convening to discuss best practices and regional approaches to addressing adverse childhood experiences.

Acknowledgements

NGA Center and the National Academy for State Health Policy thank the state officials from the Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wyoming teams for their engagement in this project and for allowing us to highlight their work in this publication. In addition, we thank the state officials in California, Tennessee, New Jersey, and Alaska for sharing their experiences and lessons learned as models for this project. We would also like to thank Sandra Wilkniss and Lauren Block for their contributions to this project during their tenure at NGA. Finally, NGA Center and the National Academy for State Health Policy also thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for its generous support of this publication and the project that made it possible.