This memo summarizes mechanisms states and territories use to fund and finance transportation systems, as well as recent Governor initiatives on state transportation revenues and resources before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Takeaways

- Over the past two years, Governors have championed and passed several changes to transportation funding and financing, raising billions for maintenance, upgrades and new projects.

- The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a devastating impact on traditional transportation revenue sources. Despite these successful efforts to raise transportation revenue, without additional federal aid, states and territories are projecting the need to make significant cuts, including canceling future projects, reducing staff, and delaying infrastructure maintenance.

Background

States and territories use a variety of funding and financing mechanisms to support the construction, operation and maintenance of transportation infrastructure. Transportation is increasingly one of the largest state expenditures at $172 billion or 8.1 percent of all state spending in 2019.

COVID-19 Impacts

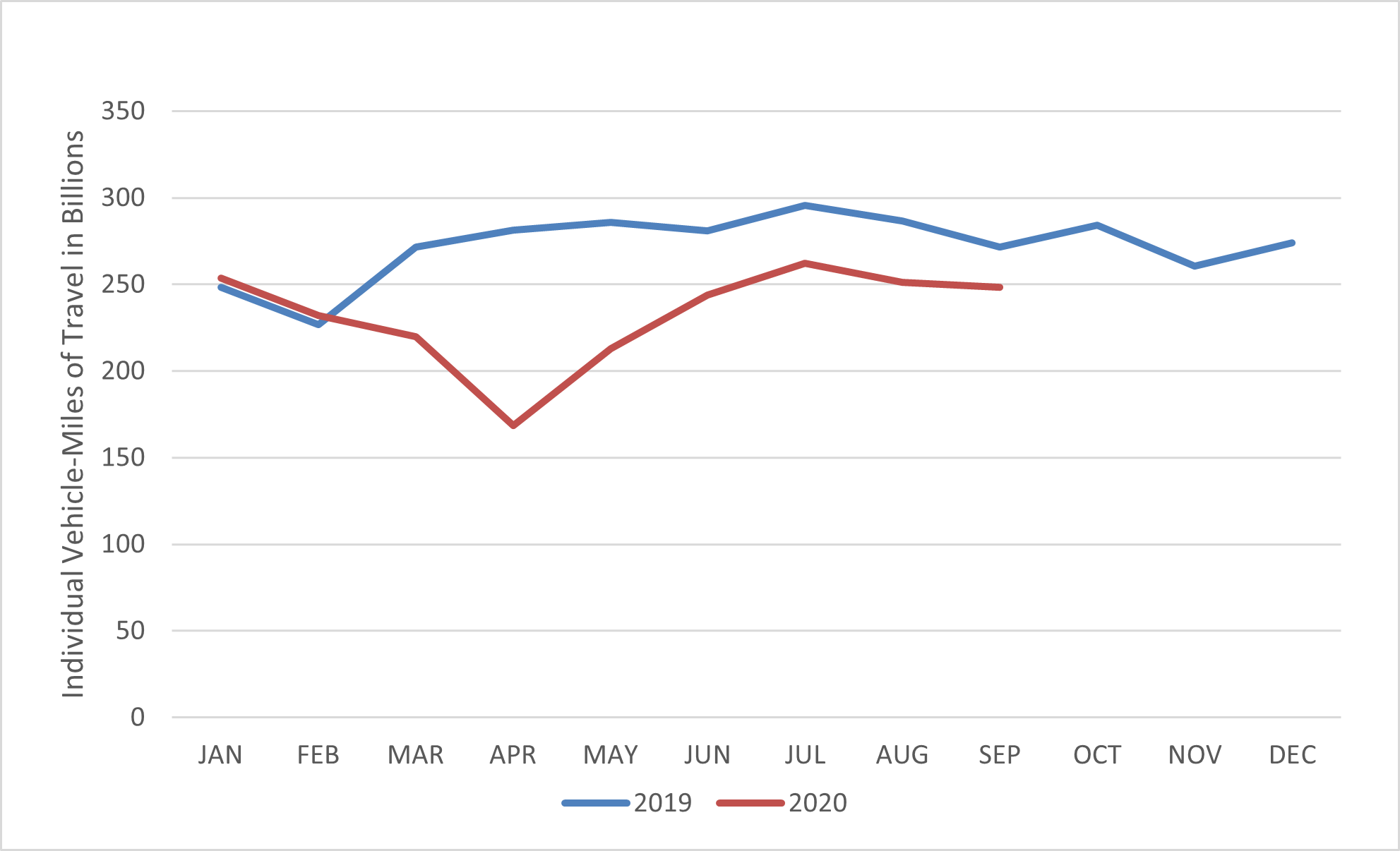

At the end of March and beginning of April 2020, Governors issued stay-at-home and closure orders to suppress the spread of COVID-19. The pandemic’s effect on travel behaviors has been steep, with early data showing an estimated 1 billion fewer miles driven each day, or an 11.4 percent decrease when compared to 2019. As a significant portion of state transportation funding comes from user fees, such as motor fuel taxes, declines in travel have had a direct impact on state transportation budgets. Density-reliant user fee revenue sources, such as transit fares, variable toll rates and congestion pricing, have been particularly hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. While gas tax revenue sharply declined during the first two months of the pandemic, these receipts have appeared to recover faster than other revenue sources, particularly when compared to user fees that rely on specific commuter patterns. Early estimates from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials project that state departments of transportation will see $16 billion in revenue declines in 2020, and $37 billion in losses over the next five years.

Figure 1: Estimated Individual Monthly Motor Vehicle Travel in the United States

As the scope and length of the pandemic continues to grow, states are revising budget projections for both FY20 and future years. For example, the Maryland Department of Transportation released a draft six-year capital budget with $2.9 billion in reductions—$1.9 billion of which is specifically as a result of COVID-19 associated revenue declines—including $500 million in delayed issuance of airport revenue bonds. California, which has recorded a 30 to 40 percent decrease in monthly passenger vehicle traffic, and a 5 to 10 percent decrease in freight traffic, forecasts a revenue loss of $1.2 billion this year and a combined $2.6 billion over the next five fiscal years. At the current trajectory, the state predicts it will take 4 to 5 years before transportation revenues return to levels experienced prior to the pandemic. Oregon reports collecting $27 million less in gas tax revenue between January and August 2020, and estimates the State Highway Fund will collect $170 million less in in 2020 and 2021. In September, Virginia predicted $870 million in lost revenue over the next two years as a result of reduced sales and vehicle taxes. Pennsylvania’s Department of Transportation reported in November that it has already lost nearly $400 million in revenue as a result of reduced travel, and expects to lose a total of $500 to $600 million in 2020.

Transit agencies have also been particularly hard hit by the impact COVID-19 has had on travel. The Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA), spanning Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia, reports the combined ridership on Metrorail and Metrobus in September 2020 is down by nearly 80 percent from pre-pandemic levels and is facing a budget shortfall of $200 million in 2020 and projections of $560 million in reduced revenue in 2021. Without additional aid, the agency has projected it would need to eliminate weekend service, reduce train frequency to every 30 minutes, cutting more than half of all bus routes, closing 19 of the 91 stations, and cutting 2,400 jobs. New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the largest transit agency in North America, has drafted an updated budget projecting a deficit of $12.4 billion between 2021 and 2024, and without additional federal aid, has projected it would need to consider reducing $1.2 billion in bus and subway services, through reduced routes and frequency, and reduce the agency’s workforce by nearly 9,400 jobs.

While many states were able to take advantage of reduced congestion to speed up active construction projects, COVID-19 also kept many projects from moving forward. As of August 2020, 28 states have announced at least one transportation project has been delayed or postponed as a result of COVID-19, either due to revenue shortfalls, delays in response to public health guidance, or disruptions in the supply chain. Transportation agencies have also incurred additional costs and delays as they have transitioned to virtual workplaces. Motor Vehicle and Licensure agencies, i.e. DMVs, face substantial backlogs and Governors have issued a variety of exemptions for expired licenses and testing requirements.

Beyond the financial implications, COVID-19 has had a direct impact on transportation operations and personnel. As of October, more than 200 transit agency employees have died from COVID-19. A recent pilot study in New York City found an estimated 24 percent of bus and subway workers had contracted the virus, though the MTA notes only 7.3 percent of the agency’s transit workers had taken leave due to the virus. Despite reduced congestion on the roadways, several states have also reported an increase in reckless driving with increased rates of speeding, crashes and fatalities, including in work zones, endangering road construction personnel.

Transportation Funding and Financing Mechanisms

Federal sources, including grants and the federal highway trust fund, account for nearly 27 percent of state transportation funding. Outside of federal funds, states raise transportation funds through a combination of motor fuel taxes, sales taxes, vehicle registration fees, tolls and other mechanisms. Most states deposit all or a portion of collected transportation revenue into a separate transportation fund. Notably, 32 states have constitutional restrictions prohibiting the use of transportation funds for non-transportation purposes.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic derailing most legislative priorities, Governors passed changes to their transportation funding and financing mechanisms, raising billions of dollars for maintenance and new projects. Below are descriptions of the various types of funding and financing mechanisms and a few of the key policy changes and Governor-led initiatives that have gone into effect, as well as information on some initiatives that emerged in response to the pandemic. Notably, several local and statewide ballot measures for transportation funding were cancelled or postponed in light of the pandemic, including in Oregon, New Jersey, and Colorado.

Funding and Revenue Sources

User Fees and Transportation Taxes

A significant portion of transportation funding sources are considered “user fees,” which consist of an excise on the use of transportation through either individual trips, reoccurring costs connected to transportation, or a fee tied to the purchase and registration of a vehicle. These fees and taxes are described below. Across the various user fee mechanisms, states often set separate rates for passenger vehicles and commercial trucks.

Motor Fuel Taxes

Fuel taxes are a fixed or indexed tax collected at the point of sale of vehicle fuel, primarily diesel and unleaded gasoline. In addition to the federal motor fuel tax, all states collect their own separate motor fuel taxes. Motor fuel taxes are the single largest source of state transportation funding, accounting for nearly 40% of all revenue. The degree of reliance on motor fuel tax revenue varies from state to state, ranging from 29 – 60 percent of state transportation funding. In 2019, states collected at least a combined $44 billion in motor fuel taxes.

Twenty states index or adjust the motor fuel tax rate based on inflation or other metrics, such as the price of gasoline. Since 2013, 30 states have increased the fuel tax rate. States typically set different rates for gasoline and diesel, with the average state gasoline tax being 25.6 cents per gallon and 26.25 cents per gallon for diesel. Further, several states have begun piloting or implementing Road Usage Charge programs or mileage-based user fees to replace or supplement the state motor fuel tax.

Key 2019 and 2020 State Funding Initiatives

In 2019, five states (Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Ohio and Utah) passed increases to their gasoline or diesel taxes. Four of the states (Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, and Ohio), included a variable-rate component to adjust the motor fuel tax over time to keep pace with inflation. In 2020, Virginia passed a gas tax increase and linked the rate to the Consumer Price Index, which prior to the pandemic was projected to raise $1 billion over the next four years.

- Alabama passed the Rebuild Alabama Act of 2019, which included a 10 cent per gallon fuel tax increase, with a phased-in adjustment to track with the National Highway Construction Cost Index over the next three years. The state also introduced an annual electric vehicle and hybrid vehicle registration fee.

- California’s SB1, originally passed in 2017 and reaffirmed by a ballot initiative, continues to provide approximately $5.2 billion per year in increased transportation revenue through a 12 cents per gallon increase in gasoline excise taxes, a 20 cents per gallon increase in diesel excise taxes, a 4 percent increase in the diesel state sales tax, and additional registration fees (highlighted below). Notably, each of these revenue sources include an annual inflationary adjustment, and the revenue funds a “Fix it First” program for deferred maintenance projects on state highways, while providing funding to enhance trade corridors, transit, and active transportation facilities, in addition to repairing local streets and roads throughout California.

- In 2019, Delaware levied a 5 cent per gallon tax on certain types of jet fuel and passed a bond bill, raising an additional $57 million in transportation funding.

- Illinois passed the Rebuild Illinois initiative, a six-year capital plan beginning in 2019, totaling $45 billion. The state created a Transportation Renewal Fund, funded by an increase to the state gas tax from 19 cents per gallon to 38 cents, which will also be indexed to inflation via the Consumer Price Index. Eighty percent of the fund will be dedicated to surface transportation and aviation facilities, and 20 percent will be dedicated to rail and mass transit facilities. Illinois also raised vehicle registration fees and introduced an annual electric vehicle registration fee.

- In 2019, New Mexico passed legislation to begin piloting a Road Usage Charge system.

- Ohio increased the state’s motor fuel tax by 18 cents per gallon and tied the per gallon rate to the Consumer Price Index, with incremental adjustments occurring from 2019 to 2023.

- At the beginning of 2020, Oregon expanded the state’s Road Usage Charge program, OReGO, indexing the per mile rate to adjust to fuel taxes and increasing registration fees. Participants in the program pay a set rate for each mile they drive on Oregon roads.

- As of 2020, Utah implemented a new Road Usage Charge program for electric and hybrid vehicles.

- In 2019, Virginia introduced a regional gas tax for the corridor around I-81 and, in early 2020, also increased the gasoline and diesel taxes statewide, indexed for inflation.

Sales or Other Taxes

Several states raise a significant portion of their transportation revenue from general sales taxes and taxes on individual items such as alcohol and tobacco. In 2019, voters in 20 states passed over 100 transportation ballot measures, totaling $8 billion in investments. Of these passed measures, 18 were new or increased state or local sales taxes. In 2020, 12 additional local sales tax and 36 property tax measures passed on ballot initiatives, with proceeds dedicated to transportation.

Most states levy a specific sales tax on the purchase of new or used vehicles, typically ranging between 4 and 8 percent.[iii] States also have a wide variety of other transportation-specific taxes, including fuel storage and fuel delivery fees, tire fees, car rental fees and taxes specific to ride-hailing companies. The application of general sales taxes, in addition to taxes on the sale of gasoline or other transportation commodities such as vehicle rentals or tires, varies across states.

Key 2019 and 2020 State Funding Initiatives

- In November 2020, voters in Arkansas have opted to continue a 0.5 percent sales tax with revenue dedicated to state and local highways, roads and bridges that would have otherwise expired in 2023.

- In April 2020, Kansas passed a 10-year transportation plan, dedicating a portion of the state sales tax to transportation and enabling tolls on three select projects.

- At the end of 2019, Utah passed legislation making gasoline purchases subject to sales taxes and increased the diesel tax and taxes on natural gas.

- In 2020, Virginia raised a local transportation tax in northern parts of the state on hotel rooms and increased the real estate transfer tax, with proceeds dedicated to transportation.[vii]

Vehicle Registration Fees and Taxes

Every state charges a vehicle registration fee. In 2018, license and registration fees accounted for nearly 20 percent of state transportation revenue. Twenty-eight states have also introduced an additional annual registration fee on electric vehicles, ranging from $50 to $225 per year. States also levy a number of fees on the documentation process of vehicles, including:

- License Plate Fees: The license plate cost might be included in the vehicle registration fee, or billed separately, though some states allow residents to transfer license plates from an old car to a new one.

- Title Transfer Fees: Nearly every state charges a nominal fee for the process of changing the title on a vehicle, ranging between $5 and $165.

- Lien Recording Fees: Several states charge a fee for the process of recording any lien that has been taken out on the title of a vehicle.

- Emissions/Inspection Fees: Several states charge a fee for the inspection of vehicles during either the point of sale or on an annual basis, and several states also charge a fee for emissions testing.

Key 2019 and 2020 State Funding Initiatives

For electric and hybrid vehicles, Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, North Dakota and Ohio imposed new electric vehicle annual registration fees, and Wyoming adjusted an existing fee.

- In 2019, Arizona implemented a new registration fee based on the value of the vehicle.

- California’s SB1 included a new registration fee for zero emission vehicles ($100 annually) and a transportation improvement fee (between $25-175 annually) depending on the value of the vehicle, which went into effect in 2020 and 2018, respectively.

- Florida reallocated revenue from the collection of motor vehicle license taxes ($132.5 million) away from the general fund and to the Transportation Trust Fund beginning in 2019.

- At the beginning of 2020, Nevada added new registration fees for a new tier of vehicle weighing 80,001 to 131,550 lbs.

- In 2019, Virginia increased truck registration fees and, in 2020, implemented a new annual highway use fee.

Tolls, Congestion and Cordon Pricing

In 2018, states reported collecting $14.5 billion in road and crossing tolls. Notably, tolls are typically dedicated to the maintenance or repayment of the specific road or highway that it is levied on or to a specific project; as such, only an estimated $1.5 billion in national toll revenue went to state transportation funds in 2018, or 1.4 percent of all state transportation fund revenue. As of 2018, 27 states operate tolls on roads or bridges.

States and local governments are also exploring congestion pricing or cordon pricing systems, focused on charging for vehicle travel within a specific travel lane or larger area (such as the downtown Central Business District in Manhattan) or during a specific period of time (such as rush hour). Congestion pricing systems often include a variable rate depending on the level of congestion, and can include surcharges or exemptions on different vehicle types.

Key 2019 and 2020 State Funding Initiatives

- New York established a congestion pricing program, tolling vehicles in the Central Business District of New York City. Set to begin collection in 2022, $15 billion in expected revenue will be dedicated to public transit projects and improvements.

- In 2019, Washington designated the Puget Sound Gateway project and a portion of Interstate 405 as eligible toll facilities.

General Funds

Importantly, states and territories also fund a significant portion of transportation operations and projects via allocations from their general funds. In 2018, general fund transfers accounted for 6 percent of state highway funding, and at least 18 percent of state transit funding.[i],[ii] States have also leveraged settlement payouts for transportation funds, notable cases being the Volkswagen settlement of $14.7 billion with a portion of the trust dedicated to states and Puerto Rico, and the Deepwater Horizon settlement with Gulf Coast states following the BP oil spill.

Key 2019 and 2020 State Funding Initiatives

- In 2019, Colorado increased the allocation of general fund transfers to the state’s highway funds by $100 million.

- Louisiana dedicated proceeds from the Deepwater Horizon, BP Oil Spill settlement to transportation projects, securitizing $50 million in annual payments to finance $700 million in projects, beginning in 2020.

- In 2019, Massachusetts appropriated an additional $200 million for a local road projects fund, $1.5 billion in federal funds for highway projects, and $200 million for transit projects.

- In 2019, New Mexico appropriated an additional $256 million for transportation projects.

- Oklahoma appropriated $30 million from the state’s FY2020 general fund to a County Improvements for Roads and Bridges Fund.

- West Virginia dedicated $54 million from a 2019 budget surplus to the State Road Fund, dedicated to highway maintenance funding.[v]

Financing Mechanisms

In addition to the revenue sources discussed above for transportation funding, states and territories rely on a variety of financing options to complete projects, typically with low-cost or tax-exempt interest rates. Every state issues tax-exempt municipal bonds to finance capital for transportation projects, fund day-to-day operations, or both. There are a variety of bond structures used for transportation, including general obligation bonds, revenue bonds, and federal debt financing tools, such as private activity bonds and GARVEE bonds. Additionally, federal credit assistance is available through the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program, which provides credit assistance for qualified projects. In FY2019 and FY2020, the TIFIA program was authorized at $300 million dollars per year, which can support approximately $4 billion in loans.

Read more…

States also have access to loans and various types of credit through state infrastructure banks and revolving loan funds capitalized by a combination of federal and state funds. Authorized in 1995 and expanded in 2005, at least 33 states and territories have established state infrastructure banks that have issued some form of financial assistance.

Public-private partnerships give states the option to finance transportation projects by entering into agreements with private entities to design, build, finance, operate and maintain the project for a set period, with payment often largely based on either an availability payment structure (availability payments are based on the performance of the private partners rather than based on demand) or project-specific revenue.[ii]

To finance projects across a region, a few states have implemented special purpose districts (ex. Transportation Improvement Districts) that rely on a variety of revenue sources such as special sales taxes, user fees, tolls, or property taxes. Missouri, Ohio and Virginia actively utilize transportation districts to fund and finance projects.

Key 2019 and 2020 State Financing Initiatives

- In 2020, Connecticut authorized up to $1.6 billion in special tax obligation bonds (over FY2020 and 2021) for transportation projects.

- Idaho issued a $15 million bond in 2019 for a congestion-related project against the 1 percent annual sales tax collections from sales taxes dedicated to road work.

- Maine passed a $105 million bond for transportation projects, with $90 million set aside for surface transportation construction and maintenance and $15 million for pedestrian, bicycle, port, rail and aviation facilities. In July 2020, voters authorized the general obligation bonds in a ballot initiative. Maine also passed legislation to allow for the creation of multijurisdictional transportation districts, with the authority to issue infrastructure bonds, raise funds for operations and capital projects, and support financing initiatives.

- At the beginning of 2020, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer requested $3.5 billion in revenue bonds for 122 surface transportation projects.

- Minnesota passed a $6.7 billion transportation finance bill, with $100 million in new appropriations for transportation funding in 2019. In 2020, the state passed a $1.9 billion construction bond package, with $627 million for transportation projects, including local grant programs.

- Missouri issued a $300 million bond in 2019 to repair more than 200 bridges.

- Montana issued infrastructure bonds for nearly $33 million in projects in April 2020, as a part of an $80 million infrastructure package passed in 2019, including $3 million for seven bridge projects across the state.

- The North Carolina Council of State approved a $700 million bond sale for the Department of Transportation in October 2020 as a part of the $3 billion “Build NC Bonds” initiative, which originally passed in 2018. This money will be repaid by a combination of highway use taxes, motor fuel taxes, and title and registration fees.

- In October 2020, the Oklahoma Department of Transportation issued $193 million in revenue bonds through the Oklahoma Capitol Improvement Authority, headed by Governor Kevin Stitt.

- Washington approved the issuance of $1.5 billion in transportation bonds over the next ten years, beginning in 2019, first paid from toll revenue and then backed by a pledge of fuel tax and vehicle-related fee revenues and the full faith and credit of the state.

Conclusion

In both 2019 and 2020, Governors implemented significant changes to the funding and financing mechanisms for maintenance and expansion of state transportation infrastructure. Due to the traditional reliance on user-fee revenue sources, the reduced travel behaviors due to COVID-19 have had a tremendous impact on the transportation budgets of nearly every state and territory. Governors have responded with new initiatives to raise needed funds, including deploying innovative programs, such as Road Usage Charging and Congestion Pricing, and expanding borrowing by issuing new bonds. However, without additional federal aid, states and territories are projecting the need to make significant cuts, including canceling future projects, reducing staff, and delaying maintenance.

Throughout the next year, NGA will continue to work with state experts and stakeholders to share the latest information and best practices for Governors to leverage innovative financing mechanisms as states and territories recover from the coronavirus pandemic and invest in modernizing their infrastructure.

For questions or requests related to the contents of this memo, please contact NGA staff: Jake Varn (jvarn@nga.org; 202-920-7453)

All NGA COVID-19 memos can be found here, or visit COVID-19: What You Need To Know for current information on actions States/Territories are taking to address the COVID-19 pandemic; as well as advocacy, policy, and guidance documents for protecting public health and the economy.