Maternal and Infant Health

While the United States is a high-income country with advanced medical facilities, the state of maternal health in the US is a matter of concern.

Tackling the Maternal and Infant Health Crisis: A Governor’s Playbook

Dear Partners,

Over the past year, many of us have traveled across the country to learn more about our national maternal health crisis, a journey that we in New Jersey began in 2018 as a first step to face our home state’s unacceptable racial disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes.

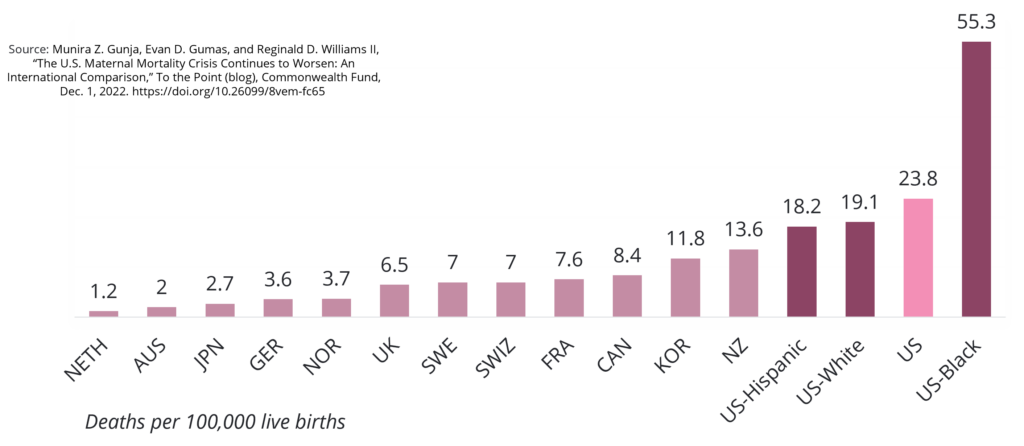

As the wealthiest country in the world, the United States should be at the cutting-edge of maternal health care. Every mother and baby across our nation should begin their life together in health, wellness and joy. But tragically – and astonishingly–that is not the case. In fact, the United States has a maternal mortality rate more than double that of other high-income countries like Norway and Germany.

In stark contrast to these disturbing statistics is our shared resolve to end this crisis. In visiting communities across the nation – from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles to Detroit to Philadelphia – we have not only learned more about the causes and consequences of our maternal and infant health crisis, but we have also seen an overwhelming and universal commitment to protecting our mothers and babies. No matter what state we visited or the political, socio-economic, racial, or religious makeup of the community, we saw again and again that ensuring our families begin their lives together intact and healthy is a responsibility in which we all share and to which we are innately connected.

In that spirit, we are thrilled to release the National Governors Association Maternal and Infant Health Initiative Playbook, a guide designed to make transformational change in a system that has historically failed our mothers and babies, especially our Black, Hispanic and American Indian and Alaskan Native mothers and babies. Of course, no one knows the unique challenges of a community better than the members of that community. Therefore, as you utilize this Playbook, we challenge you to start by sitting and listening to those most impacted, the moms and families across your state. And, as you progress in this work, we hope you will continue to collaborate with us to share your successes and amendments such that all of us might move forward together.

Communication and partnership are truly the linchpins of our strategy to improve our maternal and infant health outcomes on a national scale. Ultimately, it will be all of our voices, resources and commitment that together make the United States the safest nation on earth to deliver and raise a baby.

So, I thank you for your shared commitment to every mother and baby across the United States, and I look forward to continuing this work together.

My very best,

Tammy Snyder Murphy

First Lady of New Jersey

2022-2023 Chair of the National Governors Association Spouses Program

Executive Summary

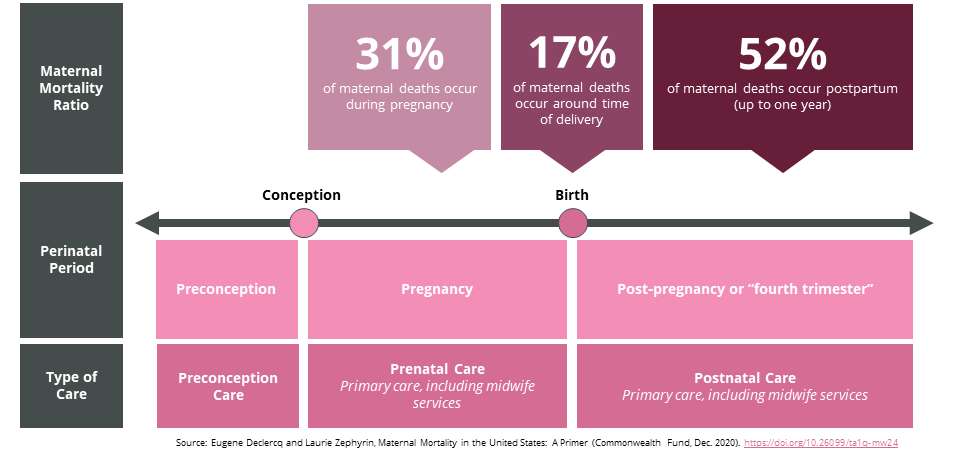

The United States has the worst rates of maternal mortality among developed countries, and the gap between rates in the U.S. and other high-income countries is widening. Despite federal and state funding and attention targeting the issue, poor adverse outcomes persist. Traditionally, interventions to address maternal mortality have focused on supporting labor and delivery; however, maternal risk extends beyond birth with 31 percent of maternal deaths occurring during pregnancy and a staggering 52 percent of maternal deaths occurring post-partum, up to one-year post-birth.

Racial disparities are especially evident for Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native mothers, who are two to three times more likely than white mothers to die from childbirth, even when holding economic and education levels constant. Maternal care in rural communities is also limited as almost 2 million rural women of childbearing age live in maternal care deserts, where there are no obstetric services within a county of residence. There are also heavy financial costs associated with high rates of maternal mortality and untreated perinatal mental health conditions with some estimates of the associated costs as high as $32.3 billion per year from conception through the child’s fifth birthday.

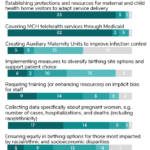

Despite the prevalence of these poor outcomes, the majority of maternal deaths are preventable. Many states are already taking action to build more cohesive and aligned approaches to reducing poor birth outcomes. States can play a vital role in advancing and bolstering these efforts, and this report outlines 32 policy recommendations that are already in practice and feasible for state governments to implement.

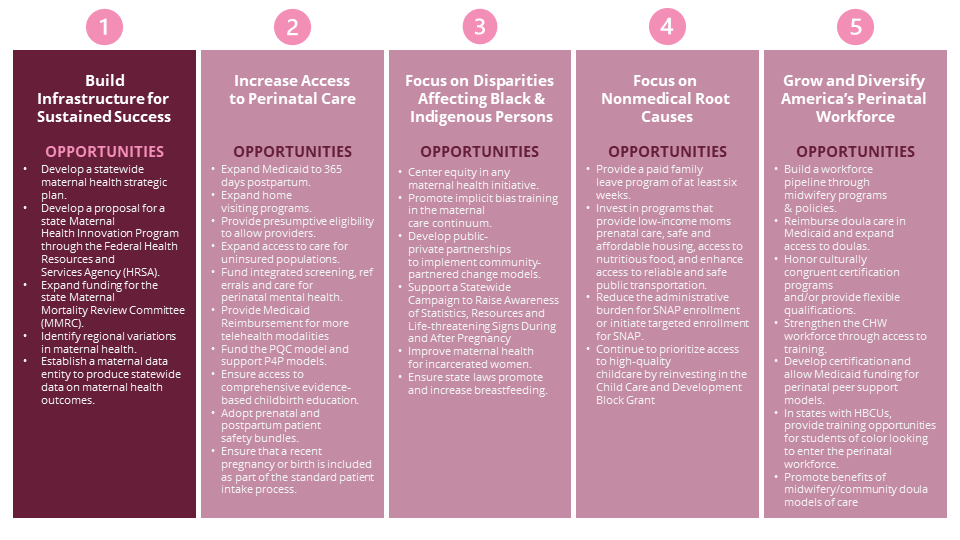

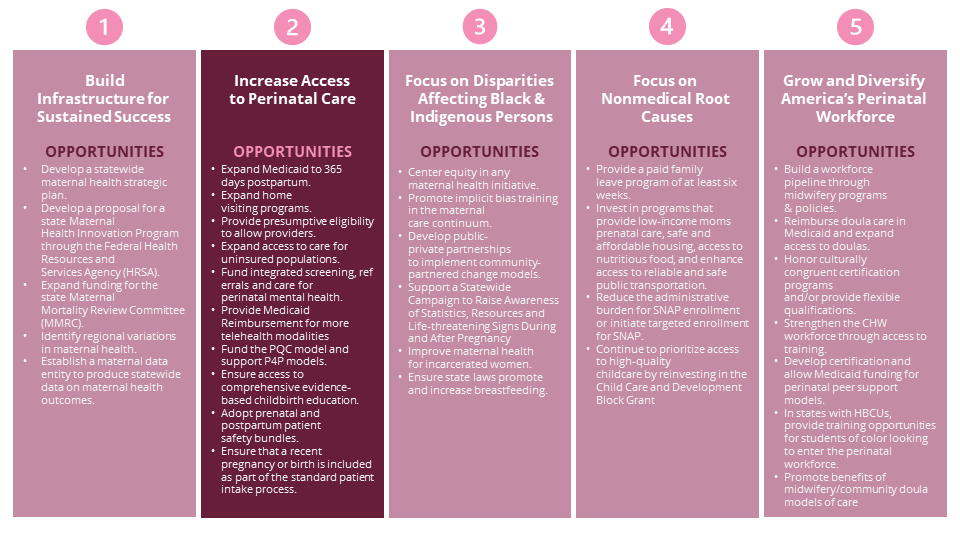

Build Infrastructure for Sustained Success

- Develop a statewide maternal health strategic plan.

- Develop a proposal for a state Maternal Health Innovation Program through the Federal Health Resources and Services Agency (HRSA).

- Expand funding for the state Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC).

- Identify regional variations in maternal health.

- Establish a maternal data entity to produce statewide data on maternal health outcomes.

Increase Access to Perinatal Care

- Expand Medicaid to 365 days postpartum. Expand home visiting programs.

- Provide presumptive eligibility to allow providers to treat pregnant people when they first seek prenatal care rather than waiting until after Medicaid eligibility is reviewed and determined.

- Expand access to maternal and infant care for uninsured populations.

- Fund integrated screening, referrals and care for perinatal mental health.

- Provide Medicaid Reimbursement for more telehealth modalities.

- Fund the PQC model and support P4P models.

- Ensure access to comprehensive evidence-based childbirth education.

- Adopt prenatal and postpartum patient safety bundles.

- Ensure that a recent pregnancy or birth is included as part of the standard patient intake process.

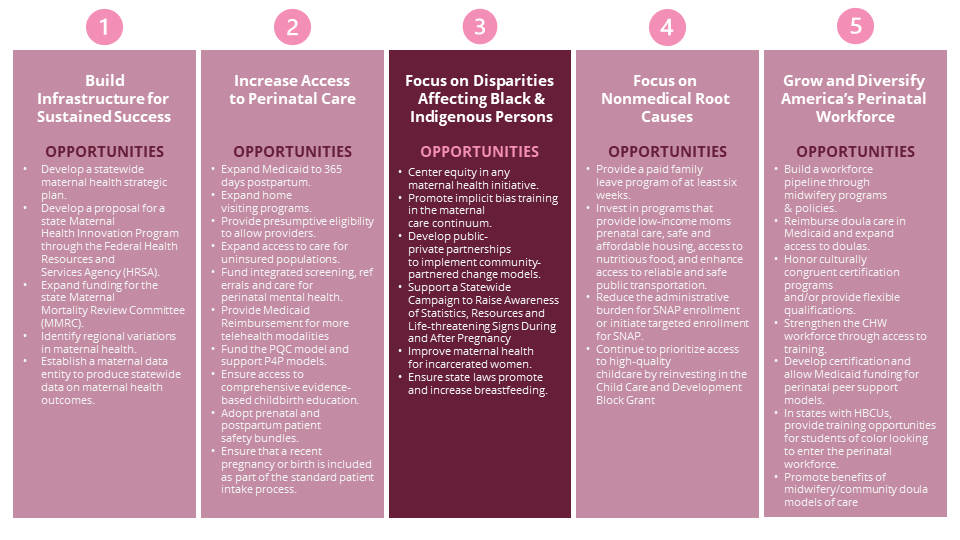

Focus on Disparities in Affecting Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native Persons

- Center equity in any maternal health initiative.

- Promote implicit bias training in the maternal care continuum.

- Develop public-private partnerships to implement community-partnered change models.

- Support a statewide campaign to raise awareness of statistics, resources and life-threatening signs during and after pregnancy.

- Improve maternal health for incarcerated women.

- Ensure state laws promote and increase breastfeeding.

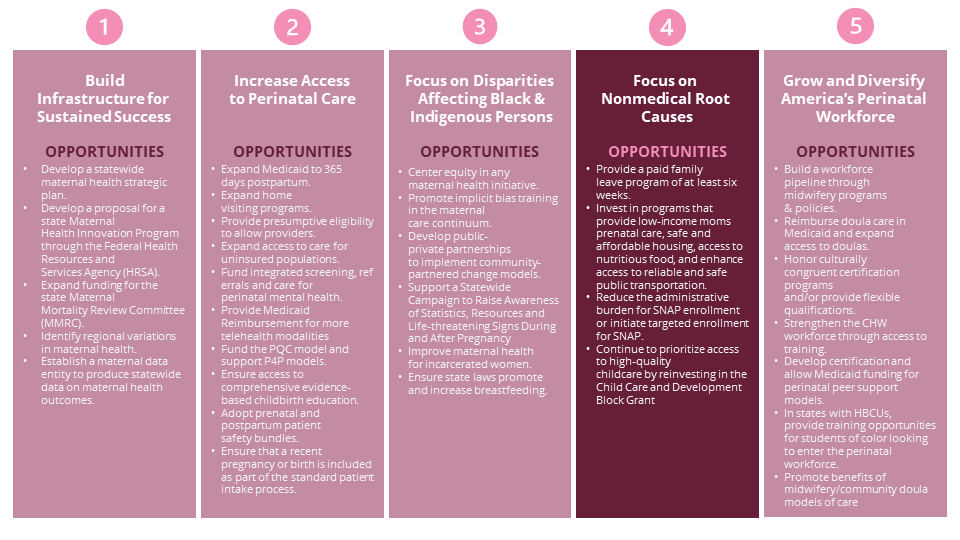

Focus On Non-Medical Root Causes

- Provide a paid family leave program of at least six weeks.

- Invest in programs that provide low-income moms prenatal care, safe and affordable housing, access to nutritious food, and enhance access to reliable and safe public transportation.

- Reduce the administrative burden for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) enrollment or initiate targeted enrollment for SNAP.

- Continue to prioritize access to high-quality childcare by reinvesting in the Child Care and Development Block Grant.

Grow and Diversify America’s Perinatal Workforce

- Build a workforce pipeline through accredited midwifery programs and policies that promote midwives.

- Reimburse doula care in Medicaid and expand access to doulas.

- Honor culturally congruent certification programs and/or provide flexible qualifications.

- Strengthen the community health worker workforce through certification and increased access to training.

- Develop certification and allow Medicaid funding for perinatal peer support models.

- In states with Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), provide training opportunities for students of color looking to enter the perinatal workforce.

- Promote benefits of midwifery and community doula models of care.

While these recommendations are feasible to implement, they will require careful planning, resourcing and coordination, where relevant, across state agencies, territories and communities, alongside non-profits, philanthropy and the corporate sector. State-level leadership and action is vital to the success of reducing adverse outcomes in maternal health; however, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. In addition, the relationship amongst sovereign Tribal Nations, states and the federal U.S. government underscores the importance of collaborative policy development to address maternal and infant health.

While these recommendations are feasible to implement, they will require careful planning, resourcing and coordination, where relevant, across state agencies, territories and communities, alongside non-profits, philanthropy and the corporate sector. State-level leadership and action is vital to the success of reducing adverse outcomes in maternal health; however, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. In addition, the relationship amongst sovereign Tribal Nations, states and the federal U.S. government underscores the importance of collaborative policy development to address maternal and infant health.

This Playbook presents pathways to consider. States are encouraged to use this toolkit as a guide and ultimately take actions that fit within individual state context and respond to the needs of their communities.

Introduction

Every year, the National Governors Association (NGA) hosts initiatives to inform Governors, spouses and state policymakers on best practices to holistically address critical social and environmental issues across the country. The hosts of the 2022–23 Chair’s and Spouse’s initiatives, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy and First Lady Tammy Snyder Murphy, focused on youth mental health and maternal and infant health respectively. These two issues pose enduring, national challenges and have been exacerbated due to the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

This Playbook is a toolkit for immediate action to improve maternal and infant health. Many of the highlighted policies work to address the significant discriminatory policies and practices embedded in organizational structures that lead to disparities in maternal health outcomes, as poor maternal health is a key driver of poor infant health.

First Lady Murphy’s NGA maternal and infant health initiative focused on four key pillars:

- Centering Women’s Voices in Maternal Health Policy

- Improving and Utilizing Maternal Health Data

- Expanding Access to Quality of Care

- Elevating Innovative Maternal Health Policies, Programs and Technologies

The initiative included four stakeholder roundtables focused on each pillar, bringing together Governors and their staffs, experts, individuals with lived experience, philanthropic funders, advocates, nonprofit organizations and companies to identify recommendations. In addition to the roundtable discussions, the NGA maternal health team conducted site visits, extensive research and dozens of interviews to identify promising recommendations and tangible examples from across states with a bipartisan lens.

This Playbook outlines problems and offers evidence-based policy considerations with state-level examples. The 32 recommendations in this report fall into five priority areas and may be implemented in concert with critical stakeholders, such as industry and community leaders, community-based organizations, faith-based organizations and — critically — people with lived experience.

- Build Infrastructure for Sustained Success: State-level strategic planning, reporting, supportive platforms, collaboratives and centers contribute to improved, sustained outcomes for mothers, infants and their families, as well as to increased accountability.

- Increase Access to Perinatal Care: Innovative policies focused on expanding coverage, extending care (including behavioral health services) and integrating technological supports are effectively increasing access to quality and culturally responsive care.

- Focus on Disparities Affecting Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native Persons: Policies, initiatives and implementation plans that intentionally raise awareness of racial disparities in maternal and infant health causes and outcomes are necessary to ensure that mothers and families have access to respectful care.

- Focus on Nonmedical Root Causes: Outside the clinical birthing experience, policies that support paid leave, expand coverage for child care and consider the needs of families with low incomes related to food, housing and transportation significantly contribute to improved health outcomes.

- Grow and Diversify America’s Perinatal Workforce: The current perinatal workforce lacks the capacity and training to meet the needs of all mothers, infants and families, especially historically underrepresented and at-risk communities. Emerging evidence shows that expanding the workforce to professionals who serve patients in nonclinical settings and attend to needs beyond six weeks postpartum can reduce adverse maternal and infant birth outcomes.

NGA MATERNAL HEALTH INITIATIVE SITE VISITS

The year-long NGA Maternal Health Initiative was informed by four roundtables held in Salt Lake City, Utah (October 2022); Santa Monica, California (January 2023); Detroit, Michigan (March 2023); and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (May 2023). Each roundtable incorporated the lived experience and diversity of participants and had a focus on health equity, illustrating how discussions of policy look and feel in communities across the country. Site visits to local organizations in the cities where the roundtables took place highlighted how policy impacts communities. The following four organizations hosted site visits providing depth and informing policy recommendations.

Sacred Circle Healthcare, Salt Lake City, Utah

Started in 2012 as an entity of the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Sacred Circle Healthcare (SCHC) is owned and operated by the Goshutes and aims to preserve the Goshute heritage of protecting and caring for family through their work with underserved populations in their local communities. SCHC’s Circle of Care™ philosophy centers patient relationships and the Goshute tribe’s tradition of healing. With diverse providers and specialties working together in a single location, Sacred Circle Healthcare provides everything from substance use disorder treatment to pharmacy and dental services, physical therapy, primary care, radiology, mental health and more. The centers serve a broad group of populations that are underserved, including anyone eligible for Medicaid, those without insurance and people of different ethnicities, not just Native Americans.

Black Women for Wellness, Los Angeles, California

Black Women for Wellness (BWW) started as a group of six women who were concerned with the health and well-being of Black babies and, in 1994, teamed up with the Birthing Project as “sisterfriends.” This grassroots program dedicated its time and mission to matching pregnant women with “sisterfriends” — mentors who coached expecting mothers throughout their pregnancy and until the child was at least a year old. These mentorship experiences provided support systems to combat infant and maternal mortality rates. Today, BWW works in Los Angeles County and in Stockton and the San Joaquin Valley in Northern California across a range of program areas, including reproductive justice, civic engagement, environmental justice and wellness.

Birth Detroit, Detroit, Michigan

Birth Detroit is a Black-led birthing center for every birthing person experiencing a pregnancy with no active complications or increased risk for complications — also known as a low-risk pregnancy. Birth Detroit focuses on community-based maternal care by providing prenatal and postpartum care by midwives, as well as childbirth education and postpartum support. Birth Detroit was formed after a 2018-2019 survey found that the community wanted a birthing center that provided prenatal visits, education and full-spectrum support for birthing persons, respecting race, culture, language, gender identities and life experiences.

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) is one of the oldest hospitals in the country and has set up systems and practices that have been replicated in children’s hospitals across the country. The Richard D. Wood Jr. Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment was founded in 1995 to specialize in fetal diagnosis, surgery and care. Since its founding, the center has cared for more than 30,426 expectant parents from all 50 states and more than 70 countries. They use a family-centered approach that includes counseling and support services, both throughout the experience and through connections to postnatal care. They diagnose and treat myelomeningocele (spina bifida), congenital heart disease and neurologic abnormalities, among other rare conditions.

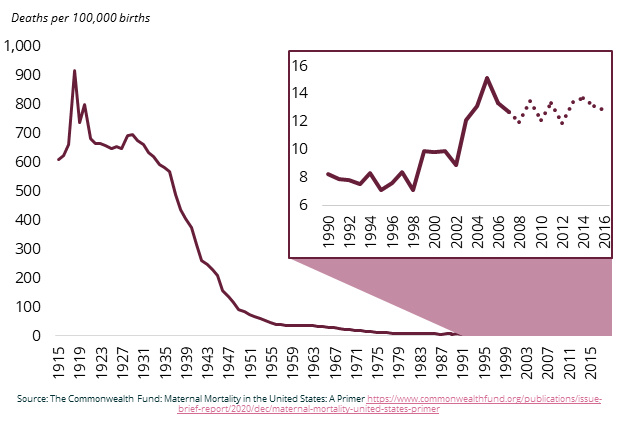

America’s Maternal Health Crisis

The United States has the worst rates of maternal mortality among developed countries, and the gap between rates in the U.S. and other high income countries is widening. The National Vital Statistics System of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the maternal mortality rate in the U.S. increased from 23.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020 to 32.9 per 100,000 live births in 2021.6F[ii] Despite federal and state funding and attention put toward the issue, adverse outcomes are disproportionately represented among Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native mothers. Traditionally, efforts have focused on supporting labor and delivery; however, maternal risk extends beyond birth and requires a more comprehensive approach to reduce poor outcomes.

Racial and geographical disparities underly these statistics. Racial disparities are especially evident for Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native mothers who are two to three times more likely than white mothers to die from childbirth, even when holding economic and education levels constant. In some states, the disparities are significantly higher. Black infants experience similar disparities in death rates as well. Maternal mortality rates for Hispanic and Latina mothers were previously on par with rates for white mothers but dramatically increased during the pandemic. Maternal care in rural communities is also limited as almost 2 million rural women of childbearing age live in maternal care deserts where there are no obstetric facilities within their county of residence. Further, only seven percent of all obstetric care providers serve rural communities.

Women who are American Indian and Alaskan Native are 4.5 times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to die during pregnancy. Between 2005 and 2014, all Americans experienced a decline in infant mortality except for American Indian and Alaskan Natives who had infant mortality rates 1.6 times higher than the non-Hispanic white population and 1.3 times the national average.

There are heavy financial costs associated with high rates of maternal morbidity and untreated perinatal mental health conditions. Maternal morbidity encompasses physical and psychological conditions resulting from, or influenced by, pregnancy. These conditions do not necessarily lead to death, but they can have a negative impact on quality of life that lasts for months, even years. A 2019 Commonwealth Fund study found evidence among nine maternal morbidity conditions, such as hypertensive disorders, and 24 maternal and child outcomes, such as cesarean section delivery and preterm birth. In 2019, these maternal morbidities and negative maternal and child outcomes resulted in an estimated total for all U.S. births of $32.3 billion from conception through the child’s fifth birthday. This amounts to $8,624 in additional costs to society for each mother-child pair annually.

The majority of maternal deaths are preventable. According to the CDC, 84 percent of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable (based on 2017-2019 data from 36 U.S. states). Mental health conditions, including deaths from suicide and overdose from substance use, are the leading cause of death during pregnancy and up to one year postpartum. Anxiety, perinatal and postpartum depression and birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder affect one in five women. Furthermore, 75 percent of women affected by mental health conditions one year postpartum do not receive treatment.

Homicide is also a leading cause of death for pregnant women in the U.S. pregnant and postpartum women are more likely to die from intimate partner violence (IPV) than the three leading obstetric causes of death, which include hypertensive disorders, hemorrhage or sepsis. In 2020, women who are pregnant or postpartum had a 35 percent higher risk of homicide compared with their peers, and 55 percent of victims were non-Hispanic, Black women. Non-Hispanic Black or African American individuals are more likely to experience adverse neonatal outcomes resulting from IPV and are more likely to be murdered during pregnancy or shortly after childbirth. Mental health and hemorrhages are now the leading causes of American Indian and Alaskan Native maternal deaths. Despite these poor outcomes, Maternal Mortality Review Committees found that between 2017 and 2019, 93 percent of pregnancy related deaths among American Indian and Alaskan Natives were preventable.

Underlying Causes Of America’s Maternal Health Crisis

Class, Culture, Sovereignty and Interpersonal and Institutional Discrimination

The direct and indirect effects of class, culture, sovereignty, interpersonal and institutional discrimination and poor social supports create compounding effects. Disparities occur across socioeconomic status, race, culture, age, geography, gender and disability status. The impacts of discrimination arise in the types of care available during pregnancy, the way care is delivered during childbirth and the systems and supports accessible to mothers, infants and families postpartum. Women who are Black, American Indian and Alaskan Native, rural or uninsured are at greater risk of experiencing these types of discrimination during the perinatal period.

As of the 2020 Census, American Indian and Alaskan Native population includes roughly 9.7 million people either identifying as American Indian and Alaskan Native alone or another racial group. Although this number represents just under three percent of the total U.S. population, it includes hundreds of distinct Tribal Nations with their own governments and cultures which requires a different set of approaches and solutions from states to address poor birth outcomes. Understanding the complex landscape of tribal jurisdiction is critical to unpacking the drivers behind these disparities in birth outcomes for American Indian and Alaskan Native outcomes. Further, tribal citizens are governed under layers of overlapping and adjacent government jurisdictions including state, federal and even country jurisdictions (for those bordering Mexico and Canada) which bifurcate the healthcare landscape. In December 2018, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights’ Broken Promises report found that Tribal Nations face a decades-long funding crisis that is a direct result of chronic underfunding of Indian health care, which contributes to vast health disparities between American Indian and Alaskan Natives and other U.S. population groups.

Black persons are also burdened by disjointed systems of care for maternal health. Having a health care workforce that is representative of the community it serves is imperative to improving access to respectful care. As an example, as of 2021 there were fewer than 15 birth centers led by and serving people of color — out of more than 380 birth centers in the U.S. There are not enough supportive resources for and protections from intimate partner violence for mothers and infants, especially Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native women. Pregnant and new mothers, along with their babies, need better access to safe situations that secure their physical and mental health, employment and the well-being of their family.

The missing village. There has been a long-standing societal focus on babies, while mothers, their partners and others who make up the “village of child care” are often deprioritized in policy discussions. When a baby is born, millions of mothers do not have adequate paid time off to heal, care for their infant or bond as a family without jeopardizing their employment. Only 21 percent of U.S. workers have access to paid family leave through their employers. Further, there is not an accessible and affordable child care system to enable families to maintain steady employment and income. In 2021, one in three working families in the U.S. struggled to find needed child care. In the last five years, funding to increase access to childcare increased by 47 percent nationally. Further, there are no supports, universal education or health care services for fathers and partners in the perinatal health care system, yet one in ten fathers and adoptive parents experience postpartum depression, and they are often critical caregivers for both mothers and infants.

Insufficient coverage and a medical birth orientation. The approach to supporting pregnancy and childbirth in the U.S. has been clinically focused since the early 20th century, and there are few options for women and families to access culturally competent, community-based care. Peer countries to the U.S. have better maternal and infant health outcomes because their health care systems integrate community-based options for families, including access to doulas, lactation consultants and community health workers. Incorporating this expanded workforce into the maternal and infant system of care has also proven to lower costs.

Coverage for maternal health care has also been limited, though there have been recent efforts to expand coverage. In the U.S., perinatal care was established as an essential health benefit and required in health insurance coverage as recently as 2010. Extending Medicaid coverage beyond 60 days postpartum only began within the last two years, and even now this policy is only in select states. Additionally, Medicaid provided ten standard pediatric visits for infants within the first two years of life, but only provided mothers with one or two.

Leading institutes and associations are now calling for expanded coverage. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recently changed their guidance to call for more emphasis on the postpartum period, and Bright Futures, the guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics, now includes maternal depression screening at four visits within the first year. Finally, despite the aforementioned evidence connecting maternal mortality and morbidity to mental health, there is no standard comprehensive mental health benefit integrated into federal Medicaid benefits and few maternal quality or equity measures.

ROADMAP LEXICON

Below are technical terms used frequently throughout the Roadmap.

Maternal mortality ratio: Death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes. Used by the World Health Organization in international comparisons, this measure is reported as a ratio per 100,000 live births. When we examine historical trends, we use maternal mortality as our index.

Pregnancy-associated mortality: Death while pregnant or within one year of the end of the pregnancy, irrespective of cause. This is the starting point for analyses of maternal deaths.

Pregnancy-related mortality: Death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from: a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy. Used by the CDC to report U.S. trends, this measure is typically reported as a ratio per 100,000 live births. In this brief, when we discuss causes of maternal deaths and current rates, we generally use pregnancy-related mortality as our index.

Perinatal: Broadly, perinatal means occurring in, concerned with, or being in the period around the time of birth. The maternal and infant health field has more recently considered the time between conception through the first year postpartum as the perinatal period.

Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (PQCs): State or multistate networks of multidisciplinary teams, working to improve outcomes for maternal and infant health. There are currently 47 PQCs across the country that aim to advance evidence-informed clinical practices and processes using quality improvement principles to address gaps in care. PCQs work with clinical teams, experts and stakeholders, including patients and families, to spread best practices, reduce variation and optimize resources to improve perinatal care and outcomes.

Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs): Multidisciplinary committees that convene at the state or local level to comprehensively review deaths that occur during or within a year of pregnancy (pregnancy-associated deaths). They include representatives from public health, obstetrics and gynecology, maternal-fetal medicine, nursing, midwifery, forensic pathology, mental and behavioral health, patient advocacy groups and community-based organizations. The CDC works with MMRCs to improve review processes that inform recommendations for preventing future deaths and has funded MMRCs in 39 states and one U.S. territory.

At-risk populations: Women who live in the U.S. South, Midwest and rural counties or are Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native or uninsured face the greatest vulnerabilities to poor maternal health outcomes.

In The Face Of Crisis, Momentum On Reversing The Tide

U.S. states and territories have significant influence over women’s access to high-quality care during the perinatal period. Despite increased funding and attention toward the issue, rates of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality have seen minimal reductions, and inequities have, in some cases, increased. However, this is changing. Fueled by new data, increased focus from government leaders at the state and federal levels (see the 2022 White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis), growing media attention and thoughtful state-level planning, trends are starting to reverse.

At a national level, media attention and improved data and research are contributing to increased attention and guidance for states and territories. The March of Dimes Report Card, which reports on the condition of maternal and infant health across 53 states and territories, is released annually and serves as an important resource for states to identify the problems specific to key geographies and populations within individual states. National media outlets, such as the New York Times, are now frequently increasing mainstream attention to the issue.

States, including New Jersey and North Carolina, are developing state-level plans that engage diverse actors including state agencies, private philanthropy, community leaders and corporate partners in their design and execution. Private philanthropy is playing a critical role in facilitating connections across these actors by supporting infrastructure for collaboration, building databases (such as in California), investing in research and closing the divide between state government and community. See: Philanthropy’s Role in Advancing Maternal Health Equity: Collaborative Action and Funder Alignment for more detail on philanthropy’s role in advancing maternal health across states.

PHILANTHROPY’S ROLE IN ADVANCING MATERNAL HEALTH EQUITY: COLLABORATIVE ACTION AND FUNDER ALIGNMENT

Philanthropy plays a crucial role in partnering with state governments to address the urgent issue of maternal mortality and improve maternal health outcomes, particularly for marginalized communities. There are already several initiatives that showcase how collaborative action between philanthropy and state governments can achieve significant progress in policy design, awareness building, data systems improvement, policy implementation support and funder coordination.

Funding for Comprehensive State-Level Plan Design:

- The Perinatal Health Equity Collective in North Carolina, convened by the Department of Health and Human Services, developed the statewide Perinatal Health Strategic Plan, focusing on enhancing maternal and infant health.

- The Nicholson Foundation and the Community Health Acceleration Partnership (CHAP) funded in partnership with the Office of the New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy’s and First Lady Tammy Snyder Murphy’s offices, the creation of the Nurture New Jersey 2021 Strategic Plan which outlines goals for policy reform and provides actionable recommendations to improve maternal health outcomes.

Improving Data Systems:

- The California Health Care Foundation (CHCF) has worked on enhancing maternal health data systems to better understand and address health care disparities, including the publication of the Maternity Care in California report, which provides an overview of maternal care and health outcomes in the state.

- The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative built a birth equity dashboard across partner hospitals, facilitating data-driven quality improvement initiatives.

Collaborative Policy Design and Implementation Processes:

- The National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), supported by philanthropic funds such as the Pritzker Children’s Initiative, provides resources and toolkits to help states improve maternal and infant health, including promoting Black maternal health and equity.

- The New Jersey Department of Health supported HealthConnect One to establish the New Jersey Doula Learning Collaborative, enhancing the number of trained community doulas and advocating for equitable compensation and reimbursement.vi Funders also supported the involvement of community doulas in the development of the state’s Medicaid reimbursement.

Supporting Narrative Change and Awareness Building:

- Every Mother Counts funded the film Giving Birth in America: Arkansas to raise awareness about the high maternal mortality rate in Arkansas.

- Narrative Nation’s podcast series Birthright, funded by CHCF and the Commonwealth Fund, amplifies positive birth stories of Black mothers and educates communities and health care providers.

Funding for Government Secondment Positions

- The New Jersey Birth Equity Funders Alliance is funding a two-year position for the director of the Nurture NJ effort, which will later transition into a permanent role within the Maternal and Health Innovation Center, an independent entity that works alongside state government and the first-of-its-kind maternal and infant health innovation center for excellence.

- Funders in North Carolina supported a philanthropy liaison position to build, strengthen and institutionalize relationships between state government and the philanthropic sector across a range of issues, including maternal and child health.

Funder Coordination and Alignment at the State and National Level

State-Level Alliances:

- The Birth Equity Catalyst Project (BECP), funded by CHAP, the Pritzker Children’s Initiative and Cambia Health, in partnership with Afton Bloom and Boldly Go, aims to address birth equity disparities through collaboration and collective action. Inspired by the New Jersey Birth Equity Funders Alliance, BECP aims to share effective models of philanthropic practice with other state funders looking to drive resources towards addressing inequities in birth outcomes.

National Funder Alignment:

- The Funders for Birth Justice and Equity is a national alliance of funders that works towards aligning and coordinating funders’ efforts to reduce racial disparities in birth outcomes.

- The inaugural Birth Equity Funders Summit (BEFS) in November 2022 brought together over 100 funders to reflect on philanthropy’s role and identify opportunities for collaboration and alignment, with a recently published BEFS report that outlines recommendations for philanthropy to advance birth justice and equity.

Priority 1: Build Infrastructure For Sustained Success

Maternal and infant health is a multifaceted issue that cuts across a vast array of domains in state government and stakeholder groups. State level planning, coordinated implementation and investment in infrastructure are necessary to drive concerted policy shifts. It is also critical to include lived experience voices and to center health equity in this work.

Most states have basic infrastructure in place to address maternal and infant health, such as a Maternal Mortality Review Committee (MMRC) and a state Perinatal Quality Collaborative (PQC), as well as a public health department or others that administer programs to target maternal and infant health issues. But few jurisdictions have articulated comprehensive strategies that are data informed and community inspired, identifying the unique needs within the state and laying out the full set of actions required to reverse disparities.

The collection, analysis and use of data is critical in ensuring continuous improvement and enhanced accountability. In states where there are many small, diverse populations, incomplete data practices can limit the insights into disparities and thus bar states’ ability to create solutions that meet the unique needs of different communities. For example, relatively small populations, like American Indian and Alaskan Native residents, are often overlooked, underfunded and left out of policy agendas, resulting in harm, despite having great health disparities. National reports and public data sets often fail to provide detailed information on American Indian and Alaskan Native people. Limited infrastructure to adequately support the relationships between state governments and leadership of sovereign Tribal Nations can also inhibit comprehensive solutions and resources that target specific groups. Further, creating and funding public awareness campaigns to reach families is another important role the state can play. This requires working with community leaders on tailored messaging to reach mothers and parents. Ensuring women’s voices are at the center of all this work is critical and will enable the development and funding of culturally competent programs.

OPPORTUNITY 1: DEVELOP A STATEWIDE MATERNAL HEALTH STRATEGIC PLAN AND ENSURE THAT BROAD REPRESENTATION IS AT ITS CENTER.

Governors can improve their state’s maternal health outcomes by creating and carrying out a comprehensive plan that engages multi-sector and community leaders in its design and execution. Many state departments and agencies intersect with and impact maternal and infant health, such as departments of health and human services, corrections, transportation and workforce development. It is helpful if a single agency or the Governor’s office champions the work and coordinates data sharing for holistic evaluations with relevant stakeholders, including community members and those directly impacted, to create a data-informed and community-inspired plan. Concerning community member outreach, a key step in developing a statewide strategic plan with broad representation may involve state governments convening with the Tribal Nation(s) in their state to identify the representatives to inform the plans and programs that aim to address maternal mortality and morbidity.

State Spotlight: The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) launched its 2020-2023 Mother Infant Health & Equity Improvement Plan after “collaborating with communities to overcome barriers and build trust.” MDHHS is working alongside nine local and national maternal-infant health stakeholders to work toward zero health disparities, including Regional Perinatal Quality Collaboratives (RPQCs); Birth Detroit; Focus: HOPE; STRONG Beginnings; Michigan Maternal Mortality Surveillance (MMMS), Fetal Infant Mortality Review (FIMR); Women, Infants & Children (WIC); Michigan Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health (MI AIM) and the Obstetrics Initiative (OBI). The New Jersey Nurture NJ plan, developed in partnership with 19 state departments and agencies and hundreds of partners including moms and families, outlines over 70 recommendations that target access to care, equitable systems of care and providing community environments that ensure women have the opportunity to be healthy. The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, with philanthropic partners, developed the statewide Perinatal Health Strategic Plan, focusing on enhancing maternal and infant health. The Attorney General’s office in the State of Washington established a new state policy that requires Tribal consent and consultation prior to the initiation of a program or project that directly and tangibly affects Tribes, Tribal rights, Tribal lands and sacred sites.

Opportunity 2: DEVELOP A PROPOSAL FOR A STATE MATERNAL HEALTH INNOVATION (MHI) PROGRAM THROUGH THE FEDERAL HEALTH RESOURCES & SERVICES ADMINISTRATION (HRSA) TO SUPPORT STATE PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE.

The purpose of the State Maternal Health Innovation (MHI) program is to support state-led demonstrations focused on improving maternal health through quality services, a skilled workforce, enhanced data quality and capacity and innovative programming. This program also engages public health professionals, providers, payors and consumers through state-led Maternal Health Task Forces. These task forces review state-specific maternal health data and implement evidence-based interventions and innovations that address critical gaps.54F[i]

State Spotlight: Two cohorts of nine states each received MHI grants for a five-year period. Iowa was awarded a grant in 2019 to develop an Iowa Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. The Collaborative aimed to improve state-level maternal health data and surveillance, implement initiatives to address workforce shortages for obstetrical care, expand existing telemedicine initiatives to increase access to maternal-fetal medicine specialists and mental health professionals, and address health disparities in maternal health outcomes and access to care.55F[ii]

Opportunity 3: EXPAND FUNDING FOR THE STATE MATERNAL MORTALITY REVIEW COMMITTEE TO IMPROVE MATERNAL HEALTH DATA COLLECTION AND SHARING TO REDUCE PREVENTABLE PREGNANCY-RELATED DEATHS.

Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) identify medical and social factors that contribute to maternal deaths and inform priorities for states to better prevent maternal mortality. In the past, MMRCs have identified complications such as maternal depression, the need for safe transport, specific risk disparities for those experiencing domestic violence, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and hemorrhage as significant risk factors. Two best practices include (1) standardizing data collection between states to ensure that no maternal death is missed and (2) including community perspectives to have a more comprehensive understanding of the factors contributing to maternal deaths. The inputs and findings elevated by the MMRCs should inform the state-level goals and strategies, specifically informing perinatal quality collaboratives regarding which health areas can be improved.57F[ii] Finally, there is a specific need to mobilize state agencies alongside Tribal Nation representatives to improve racial and ethnic data to accurately represent American Indian and Alaskan Native people, including oversampling of American Indian and Alaskan Native persons to address small sample size concerns.

State Spotlight: Thirty-nine states have obtained funding from the CDC through the Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality (ERASE MM) Program to improve data collection on maternal morbidities in their states. Through these mechanisms, policymakers can identify maternal and infant health risks and recommend data-informed policies to address these needs. For example, the Mississippi Department of Health recommends that preconception counseling is available to women with high mortality medical conditions and that state agencies provide information on location and operating hours of emergency care in rural areas. The Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Section in Nevada recommends educating providers on Nevada’s substance use disorder treatment options, which already exist for pregnant women, and removing barriers to care. The Maternal Mortality Review Committees in Texas and Oklahoma have added seats to include people with lived experience to identity gaps in maternal healthcare. Ohio implemented a data-sharing arrangement between the Department of Health and Department of Administrative Services to link longitudinal data on maternal engagement with state systems in support of identifying health risks while expanding and evaluating the home visiting program for at-risk mothers. States may also include Tribal Epidemiology Centers, which are also legally recognized Public Health Authorities, in MMRCs to promote better data quality, collection, collaboration and security.

OPPORTUNITY 4: IDENTIFY REGIONAL VARIATIONS IN MATERNAL HEALTH.

A landscape analysis of the maternal and infant health variations can identify the communities that are most susceptible to maternal health disparities and better inform interventions. Under the federal Data Mapping to Save Moms’ Lives Act, states should soon have access to maps from the Federal Communications Commission that overlay broadband access with maternal health data.

State Spotlight: The New York State Department of Health analyzes 18 maternal and infant health outcomes such as infant mortality, preterm birth and low birthweight to determine maternal and infant health hot spots across the state.

OPPORTUNITY 5: ESTABLISH A DATA ENTITY THAT PRODUCES STATEWIDE DATA ON MATERNAL HEALTH OUTCOMES AND PARTNERS WITH HOSPITALS TO IMPLEMENT BETTER PRACTICES.

Data can inform states on the scope of disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes. There are commonly used population-based information sources that may have maternal and infant data, but data utility can significantly improve under an established entity tasked with and committed to implementing better collection and evaluation practices. It is also important to rely on existing and available data where possible to avoid further burdening people with lived experiences by relying solely on their voices to demonstrate maternal and infant health disparities.

State Spotlight: Since 2006, the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) has worked to improve maternal outcomes by gathering data on maternal mortality and analyzing maternal morbidities and disparities through the CMQCC Maternal Data Center. CMQCC has produced four publications on quality improvement measures for the state of California and authored more than 70 research publications on maternal health.

Priority 2: Increase Access To Perinatal Care

A 2020 report by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) notes that in an ideal maternal health system, all people would have access to comprehensive, seamless medical and behavioral health care as well as economic and social supports. Additionally, they would be engaged with this system before, during and after pregnancy, and care would be available in places more proximate than a hospital. The majority of women in the U.S. do not receive this type of care.

For most Americans, access to health care starts with health insurance. Health care coverage before and after pregnancy is associated with better health outcomes for both mother and infant. One example is coverage for prenatal care. Babies of mothers who do not get prenatal care are three times more likely to have a low birth weight and five times more likely to die than those born to mothers who do get care. With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), health insurance coverage expanded dramatically for most citizens of the U.S. However, there is more that states can do to ensure that prenatal, delivery and postpartum care are available to women through a comprehensive insurance coverage plan.

Health insurance coverage should include support for perinatal mental health and substance use disorders, from screening through treatment, to address the leading causes of maternal mortality. Coverage could also include postpartum care that extends beyond the traditional single visit six weeks postpartum. Slightly more than half (52 percent) of all deaths occur after the day of delivery through one year postpartum, while almost one-third (31 percent) occur during pregnancy.

Ultimately, it is critically important for both commercial and public health insurance to include robust perinatal coverage, especially behavioral health services and longer-term postpartum care. The ACA greatly improved coverage of maternity health services. In particular, 20 million people have gained coverage, financial assistance has become available to purchase coverage and the quality of coverage offered has been improved. But there are still significant differences among states in the prenatal, labor and delivery, and postpartum services covered. Specifically, the ACA requires small group and individual market plans to cover maternity and newborn care among the required essential health benefits (EHBs), but states are able to select a benchmark plan to define the specific services covered under each category which can serve to limit coverage. Similarly, there is a great deal of variation in services and outcomes offered through Medicaid. In 2021, 41 percent of births in the U.S. were financed by Medicaid. However, compared to women with private health insurance, women with Medicaid coverage were more likely to report: no postpartum visit, returning to work within two months of birth, less postpartum emotional and practical support at home, lack of decision autonomy during labor and delivery, being unfairly treated and disrespected by providers because of their insurance status and not exclusively breastfeeding at one week and six months.

Opportunity 6: EXPAND MEDICAID TO 365 DAYS POSTPARTUM.

Extending Medicaid coverage through 12 months postpartum is crucial to addressing the current maternal health crisis. The first year after birth is a significant period, as more than half of pregnancy-related deaths happen during this time. Extending coverage can help new mothers overcome barriers to physical and mental health care, improve health outcomes and potentially reduce disparities. Approximately 65 percent of births by Black mothers are covered by Medicaid, so extending the postpartum coverage would positively impact outcomes and reduce disparities.

Currently, the default for Medicaid coverage ends 60 days after birth, but through Section 9812 of the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act states have the option of extending Medicaid 12 months postpartum through a less cumbersome administrative processes, as well as drawing on more federal matching funds.79F[iii] The American College of Gynecology guidance notes that the postpartum period should be an ongoing process “with services and support tailored to each woman’s individual needs.” This may include physical recovery from birth, an assessment of social and psychological well-being, chronic disease management and initiation of contraception, among other services. Under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, the extension option for Medicaid postpartum coverage has been made permanent. Therefore, once states choose to extend, they will continue to receive federal matching funds.

State Spotlight: As of June 2023, 35 states have extended their postpartum coverage through a full year postpartum. Louisiana was a national leader in extending postpartum coverage. The Centers for Medicare Services approved the state’s plan amendment in April 2022. States have approached this through combinations of federal action, state plan amendments or waivers, and laws or bills.

Opportunity 7: EXPAND EVIDENCE-BASED HOME VISITING PROGRAMS.

Home visiting is a prevention strategy designed to support pregnant families, promote infant and child health, foster child development and school readiness, and help prevent child abuse and neglect. Home visiting programs are voluntary and offer vital support to parents as they manage the challenges of raising babies and young children.

States are covering these evidence-based services, such as home visiting during the perinatal period, to improve continuity of care for pregnant and postpartum people enrolled in the Medicaid Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). States leverage other federal, state, local and private funding sources to finance these services and in some cases use existing Medicaid services to cover components of home visiting.

One example of a robust universal home visiting model is Family Connects, which is part of a clearinghouse of highly effective approaches. Family Connects demonstrates improvements in child health, linkages and referrals, maternal health and positive parenting practices. It consists of one to three nurse home visits, typically when the infant is two to 12 weeks old, and follow-up contacts with families and community agencies to confirm families’ successful linkages with community resources. During the initial home visit, a nurse conducts a physical health assessment of the mother and newborn, screens families for potential risk factors and may offer direct assistance, such as guidance on infant feeding and sleeping. If a family has a significant risk or need, the nurse connects the family to community resources. Family Connects is currently implemented in 12 states.

State Spotlight: In 2019, Kansas served an estimated 23.8 percent of children under age three in families with incomes of less than 150 percent of the Federal Poverty Level in the state’s home visiting programs. As of 2021, families in the state have access to five out of a possible seven evidence-based program models that have a demonstrated impact on parenting and are designed for families with young children. In 2021, Maryland launched a maternal and child health care transformation initiative to fund the expansion of current maternal health-focused programs, which includes home visiting services. In Michigan, the statewide Maternal Infant Health Program serves over 20,000 Medicaid-eligible families, with prenatal and postnatal home visiting covered. Michigan is creating more awareness of their Home Visiting Program and other state maternal health programs by developing a mobile pregnancy app to connect users to state maternal health programs. In 2021, New Jersey joined Oregon in enacting Universal Newborn Nurse Home Visiting enabling all new moms, including those that experience a stillbirth and those that adopt, to receive up to three visits by a registered nurse in their home. Additional states with robust home visiting programs include Iowa and Maine.

Opportunity 8: PROVIDE PRESUMPTIVE ELIGIBILITY TO ALLOW PROVIDERS TO TREAT PREGNANT PEOPLE WHEN THEY FIRST SEEK PRENATAL CARE RATHER THAN WAITING UNTIL AFTER MEDICAID ELIGIBILITY IS REVIEWED AND DETERMINED.

Despite being eligible for Medicaid coverage, it often takes pregnant women days or sometimes weeks to acquire Medicaid, delaying their prenatal care and treatment. Presumptive eligibility is a policy that allows health care providers to provide temporary Medicaid or CHIP coverage to individuals who are likely to qualify for these programs but have not yet completed the application process.

State Spotlight: As of 2020, 30 states, offer presumptive eligibility for pregnant women. Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) is another policy that could increase access to Medicaid services for eligible women while also streamlining the application process. ELE allows state Medicaid or CHIP programs to rely on the application findings from other state programs, such as Head Start or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to offer health care services. As of 2021, ELE is offered in Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, South Carolina and South Dakota.

Opportunity 9: EXPAND ACCESS TO MATERNAL AND INFANT CARE FOR UNINSURED POPULATIONS.

Lawfully present immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to certain eligibility restrictions. In general, lawfully present immigrants, including most lawful permanent residents or green-card holders, must have a “qualified” immigration status to be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP and must wait five years after obtaining qualified status before they may enroll. Noncitizens, including lawfully present and undocumented immigrants, are significantly more likely to be uninsured than citizens. Medicaid expansion to households with 200 percent of the federal poverty level, allowing Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) eligible immigrants to receive CHIP prenatal services and reducing the five-year Medicaid eligibility waiting period for immigrants can cover these gaps in care during the perinatal period.

State Spotlight: In 2021, Oregon implemented the Cover All People legislation as part of House Bill 3352 to include low-income, undocumented adults in the Oregon Health Plan. As of July 2022, there is $100 million in state funding for the expansion. In July 2022, Illinois lowered the age for Medicaid eligibility for residents regardless of citizenship to 42 years old through authorization from the Illinois General Assembly.

Opportunity 10: FUND AND PRIORITIZE INTEGRATED SCREENING, REFERRALS AND CARE FOR PERINATAL MOOD AND ANXIETY DISORDERS (PMADS), PERINATAL SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS (SUDS) AND INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE (IPV).

As the most common complications in pregnancy, PMADs, SUDs and IPV are distinct yet often intertwined, and associated with a range of adverse outcomes for pregnant persons and their families. Some estimates indicate that 15.9 percent of pregnant people in the United States smoked cigarettes, while 8.5 percent consumed alcohol and 5.9 percent used illicit drugs. IPV can result in insufficient or inconsistent prenatal care, poor nutrition, inadequate weight gain, substance use and increased prevalence of depression, as well as adverse neonatal outcomes, such as low birth weight and preterm birth and maternal and neonatal death.

Routine screenings, interventions and referrals through an integrated care model for mothers and their families are essential. Markers of strong, integrated care include: training health care providers to identify mental health, substance use and IPV issues for pregnant and postpartum women, early and periodic screening that supports both identification and stigma reduction through frequent conversations with families, accessing treatment across the continuum of mild to severe issues, and working with pediatric providers to screen and support mothers and families with mental health and substance use disorders throughout the first year of well-child visits.

State Spotlight: Alabama expanded Medicaid to include screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment for early intervention and treatment of SUDs. In 2021, Louisiana began allowing separate Medicaid reimbursement for perinatal depression screenings of an enrolled caregiver during a well-child visit from birth to 365 days postpartum. In New Mexico, pregnant women of color reported receiving discriminatory substance use treatment and screening, so the New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department (CYFD) and the Department of Health (DOH) created systemic training for hospital staff to provide less stigmatizing treatment. Further, the Children’s Code was amended through House Bill 230 so that substance use during pregnancy is not singular grounds for a mandatory child abuse report. New Mexico’s amendment to the Children’s Code included a Plan of Safe Care in which families affected by substance use make a plan during pregnancy with a multidisciplinary team to ensure the health of infants and mothers. Plans of Safe Care include the following four components for care and support during the perinatal period: physical health, behavioral health to address substance use, infant health and development and parenting/family support to connect the family with social services. Currently, 33 states have Plans of Safe Care to address the needs of infants and mothers.

Opportunity 11: PROVIDE MEDICAID REIMBURSEMENT FOR MORE TELEHEALTH MODALITIES, INCLUDING LIVE VIDEO, STORE-AND-FORWARD, REMOTE PATIENT MONITORING, TELE-ULTRASOUND, REMOTE NONSTRESS TEST AND EMAIL/PHONE/FAX.

With the national increase in maternal care deserts, people across the country are being forced to travel further for perinatal care. Adoption of Medicaid reimbursement policies and ensuring that codes for these procedures allow, or even specify, that the activity can take place in the home is important because it allows patients to be monitored and cared for without the cost and burden of frequent prenatal visits.

Two U.S.-based studies investigated a combination of telehealth visits and reduced in-person visits for prenatal care to determine the feasibility of telehealth maternal care. The two studies demonstrated that telehealth resulted in higher satisfaction and lower prenatal stress for patients compared with those receiving in-person care. It is necessary to note that telehealth can only be effective if access to technology is universal.

State Spotlight: The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes, Project ECHO, is a tele- mentoring approach that brings expertise to patients in medically underserved areas by connecting specialty physicians to primary care physicians. Project ECHO, which began in New Mexico, is now one of the many maternal telehealth policies in Virginia aimed at improving health coverage and supporting the alignment of reimbursement for telehealth services across patients. In Georgia, the Healthy Babies Act was passed in 2023 to pilot a two-year maternal telehealth program for Medicaid enrollees that provides access to remote patient monitoring, remote fetal nonstress tests and tele-ultrasound. In Missouri, the Medicaid Department issued guidance clarifying that the home can be a place of service for the fetal non-stress test. In Oklahoma, expanding telehealth services for birthing women and infants is part of the Oklahoma Maternal Health Task Force 2020-2024 Strategy.

Opportunity 12: FUND THE STATE’S PERINATAL QUALITY COLLABORATIVE (PQC) TO INCREASE CAPACITY AND SUPPORT PAY-FOR-PERFORMANCE MODELS.

Nearly every state already has or is developing a PQC, which supports hospitals and clinicians to engage with quality improvement tools. PQCs have made population health improvements by improving breastfeeding rates, reducing elective deliveries without a medical indication before 39 weeks’ gestation, reducing unnecessary cesarean births among low-risk pregnant women, reducing health care setting-associated infections in newborns, bringing down rates of hemorrhage and hypertension and reducing rates of preterm births.

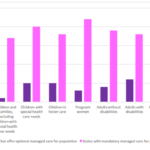

About half of states monitor or report state-level metrics related to maternal health. While most states require managed care organizations to report maternity-related quality measures to the state, few use performance improvement measures. Quality improvement tools may be more widely used by incorporating pay-for-performance models or by adopting existing perinatal risk assessment tools. There is a need to invest more resources into PQCs and provide capacity support to expand the impact of their work.

State Spotlight: To address rising maternal deaths associated with preeclampsia, Illinois’ PQC conducted a program to improve care for pregnant and postpartum women with severe preeclampsia and eclampsia in 112 hospitals. The number of women receiving medication within 60 minutes increased from 42 percent to 85 percent during the program, and the rate of severe pregnancy complications among pregnant women experiencing hypertension at delivery decreased by 41 percent.

Opportunity 13: ENSURE ACCESS TO COMPREHENSIVE EVIDENCE-BASED CHILDBIRTH EDUCATION FOR ALL MEDICAID BENEFICIARIES AS PART OF STANDARD PRENATAL CARE.

Childbirth education (CBE) is designed to help pregnant women and their support unit manage the physical, emotional and psychological changes during the perinatal period, increase their knowledge and access to community resources, improve their ability to advocate for care and increase the likelihood of positive birth outcomes. CBE is also a recommended strategy for cesarean rate reduction.

States can work with their perinatal quality collaborative to align hospital practices and philosophies with evidence-based childbirth education; assess and mitigate barriers to childbirth education; include flexible educational formats, such as interactive web-based learning; and implement prenatal care models that efficiently integrate comprehensive pregnancy and childbirth education into routine visits, such as group prenatal care.

State Spotlight: Washington’s Medicaid program offers pregnant women a series of educational group sessions with at least six hours of instruction, led by a trained educator who has both a certification or credentials from a training organization that meets the Childbirth Educator training standards set by the International Childbirth Education Association (ICEA) and a current Core Provider Agreement and National Provider Identifier (NPI), to prepare each pregnant woman and her support person(s) for labor and delivery. In Wisconsin, CBE is covered through Medicaid if a pregnant person is both at higher risk for adverse outcomes and are also enrolled in the state’s Prenatal Care Coordination program.

Opportunity 14: IMPLEMENT PRENATAL AND POSTPARTUM PATIENT SAFETY BUNDLES TO ADDRESS ONGOING QUALITY IMPROVEMENT.

Patient safety bundles are a structured way of improving the processes of patient care.108F[i] The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) is a quality improvement initiative to support best practices that make birth safer, improve maternal health outcomes and save lives by implementing best practices in hospitals. AIM developed eight bundles that include actionable steps that can be adapted to a variety of facilities and resource levels to address the leading causes of preventable maternal mortality.

State Spotlight: In Texas, the Department of State Health Services (DSHS) teamed up with AIM and the Texas Hospital Association to create the TexasAIM initiative to help hospitals and clinics carry out maternal safety projects. Currently, TexasAIM supports three AIM bundles such as the Obstetric Hemorrhage Bundle, the Obstetric Care for Women with Opioid Use Disorder Bundle and the Severe Hypertension in Pregnancy Bundle. The Texas DSHS connects any interested hospitals and clinics to resources, tools and the AIM data portal.

Opportunity 15: HOLD PROVIDERS ACCOUNTABLE FOR ENSURING THAT A RECENT PREGNANCY OR BIRTH IS INCLUDED AS PART OF THE STANDARD PATIENT INTAKE PROCESS.

Maternal and infant health outcome improvement is challenged by the number of fragmented touchpoints in a health care system that exist from conception through one year postpartum. For example, a woman may shift from a midwife-led clinic to a hospital delivery with an OB-GYN provider, then go back to a primary care provider in the postpartum period, followed by another shift to having the majority of interactions with their child’s pediatrician. Encouraging connection and communication among this system of providers is another approach to ensuring accountability for high-quality care and outcomes.

State Spotlight: In 2020, New Jersey enacted bill A5031/S3455, which requires hospital emergency departments to ask people of childbearing age about any pregnancy in the past 365 days. This simple approach could lead to catching health issues exacerbated by a pregnancy-related condition a full year postpartum.

Priority 3: Focus On Disparities Affecting Black And American Indian And Alaskan Native Persons

Stark racial disparities in maternal and infant health in the U.S. have persisted for decades despite continued advancements in medical care. It is not enough to focus on addressing gaps within the formal health care system without specifically, deliberately and inclusively putting resources toward the factors that contribute to these disparities. Notably, disparities in maternal and infant health persist even when controlling for certain underlying social and economic factors, such as education and income, pointing to the roles that interpersonal and institutional discrimination play in driving disparities.

The Kaiser Family Foundation highlights research documenting that social and economic factors, racism and chronic stress contribute to poor maternal and infant health outcomes, including higher rates of perinatal depression and preterm birth among Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native women and higher rates of mortality among Black infants. In one study, American Indian and Alaskan Native, Hispanic and Black women reported significantly higher rates of mistreatment, such as shouting and scolding or ignoring or refusing requests for help, during the course of their pregnancy. Even controlling for insurance status, income, age and severity of conditions, Black, American Indian and Alaskan Native and Hispanic people are more likely to experience a lower quality of care and less likely to receive routine medical procedures.

Governors and policy leaders can increase awareness of interpersonal and institutional discrimination and unintended biases through mechanisms like implicit bias training for all individuals that have touchpoints with mothers and children. One way to improve health outcomes and government efficiency is to break down silos across agencies, public and private institutions and providers — especially in sectors that may seem unrelated at first glance, like corrections — and to integrate care models and supports with an awareness of racism and how communities can and should lead on solutions to provide equitable care.

Opportunity 16: CENTER EQUITY IN ANY MATERNAL HEALTH INITIATIVE.

In addition to creating an equitable statewide maternal health plan, any maternal health-related initiative or policy should center equity, whether it has a clinical or community focus. States and hospital networks have centered equity in their health policies as a way to build trust and achieve optimal health for all patients. The American Medical Association offers a toolkit with five steps to embed equity into health systems to achieve optimal health for each patient.

State Spotlight: In Ohio, the Eliminating Racial Disparities in Infant Mortality Task Force published recommendations to improve maternal health as well. In Washington, University of Washington Medicine launched the Healthcare Equity Blueprint for 2022-2026 with key areas for clinical improvement to better meet the needs of marginalized communities.

Opportunity 17: PROMOTE AND PROVIDE ACCESS TO CULTURAL HUMILITY AND IMPLICIT BIAS TRAINING FOR EVERYONE IN THE MATERNAL CARE CONTINUUM.

The American Journal of Public Health published a systematic review that examined the degree to which implicit bias toward race and ethnicity exists in health care professionals and how the bias changes health care outcomes. The results revealed a significant relationship between implicit bias and four areas of patient care: patient–provider interactions, treatment decisions, treatment adherence and patient health outcomes. Implicit bias is more likely to occur in stressful situations when health care professionals are tired, busy and feeling pressured.

State Spotlight: As of 2023, the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs includes guidelines requiring nursing professionals seeking licensure or registration to complete a one-hour implicit bias course from a board-approved continuing education provider to meet this requirement within their first two years after licensure. Implicit bias training is also now incorporated into nursing training education. In 2021, New Jersey enacted a law requiring all health care professionals who provide perinatal treatment and care at a hospital or birthing center undergo explicit and implicit bias training. In North Dakota, a 20-minute implicit bias training is available on the state’s Health and Human Services website intended for professionals in healthcare, education and social services.

Opportunity 18: DEVELOP PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS TO IMPLEMENT PLACE-BASED, COMMUNITY-PARTNERED CHANGE MODELS IN AREAS WITH THE HIGHEST MATERNAL AND INFANT MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY, AND THEN EXPAND TO EVERY COMMUNITY ACROSS THE STATE.

Closing the gap between maternal and infant health disparities and reducing mortality requires engagement from stakeholders at all levels, including buy-in from the communities most impacted by these outcomes. Partnering with philanthropic groups can provide a neutral space to connect with stakeholders outside of government and support the identification of the right partners and priorities to highlight as part of this work.

State Spotlight: The Safer Childbirth Cities initiative is a nationwide effort to engage private and public stakeholders to foster local solutions and implement community-partnered change to reduce the racial inequities in maternal health outcomes. Currently, 20 cities participate in the initiative to implement strategies tailored to the needs of pregnant people in their city. A few of these strategies include community-partnered change such as incorporating integrative care, connecting women to clinics and providing doula support. In New Jersey, the Maternal Experience Survey is a community tool developed by the Atlantic City NAACP Black Infant and Maternal Mortality (BIMM) task force to improve care and reduce childbirth-related disparities for women of color. The task force is composed of health professionals, legislators, educators and community members and is responsible for building community-level action to improve the birthing outcomes for people in New Jersey. The Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona, Inc. created the Maternal Health Innovation Program and strategic plan to improve maternal health outcomes in Tribal communities. The comprehensive plan identifies seven priority areas alongside specific action items to meet their goals to improve maternal mortality and morbidity in Tribal communities in Arizona, improve access to maternal health surveillance data, and improve the maternal health partnership between Tribal communities and Arizona.

Opportunity 19: SUPPORT A STATEWIDE CAMPAIGN TO RAISE AWARENESS OF STATISTICS, RESOURCES AND LIFE-THREATENING SIGNS DURING AND AFTER PREGNANCY.

The Hear Her Campaigns are CDC public awareness campaigns to raise awareness of potentially life-threatening warning signs during and in the year after pregnancy. They encourage the people supporting pregnant and postpartum women to listen and act when concerns are expressed. Hear Her began in 2019 as a national campaign to reach Black Americans, American Indians and pregnant women and their partners in addition to healthcare providers. Community-based organizations, hospitals and many states have adopted the framework and adapted it for their state contexts.

State Spotlight: The Texas Department of Health and Human Services adapted the Hear Her Campaign to produce video PSAs, information on early warning signs and risks and stories from pregnant women. All resources are available in English and Spanish. The Arizona Department of Health and Human Services is launching a Hear Her Campaign with the following goals: increase awareness of serious pregnancy-related complications and their warning signs, empower women to speak up and raise concerns, encourage women’s support systems to have conversations with her about symptoms, and provide tools to facilitate these conversations for women and providers. In 2022, the CDC Foundation partnered with the Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health to highlight the stories of five pregnant American Indian and Alaskan Native women through the Hear Her Campaign and adapted the urgent warning signs resources to be culturally appropriate, including resources for healthcare professionals who work with American Indian and Alaskan Native populations. While the American Indian and Alaskan Native Hear Her Campaign is nationwide, Montana Obstetrics and Maternal Support includes the campaign as part of statewide maternal health resources.

Opportunity 20: IMPROVE MATERNAL HEALTH CARE FOR WOMEN WHO ARE INCARCERATED.

Up to 75 percent of women who are incarcerated are of childbearing age, and Black women are impacted at twice the rate of white women. The available estimates for the rate of pregnancy for women who are incarcerated is between three to four percent at intake. Often, incarceration is linked to higher pregnancy risk factors such as substance use, poverty and mental health conditions. Some prisons are beginning to offer perinatal support such as parenting programs, nurseries, and midwifery and doula care.

State Spotlight: In Pennsylvania, commonwealth health and corrections departments partnered with the Tuttleman Foundation and Genesis Birth Services to launch a pilot doula program for incarcerated pregnant people. The state has allocated $100,000 of American Rescue Plan Act funding as well. As part of the program, incarcerated expecting mothers have access to prenatal visits, biweekly checkups and doula support during births. The program is now expanding to include a lactation program that will allow incarcerated mothers to pump and mail milk to their babies. The 2021, Colorado Birth Equity Bill Package includes the protection of all pregnant people in their perinatal period, including incarcerated women. Protections include requirements for correctional facilities, jails and prisons to report the use of restraints on pregnant women. Similarly, Illinois has extensive laws to protect incarcerated women during the perinatal period including their right to not be shackled during birth, right to be without a correctional officer present during birth, choice in cesarean birth or epidural, right to refuse induced labor, and right to be screened for the Moms and Babies program in addition to accessing education on childbirth and pregnancy.