This publication explores strategies Governors and state leaders employed to address the long-standing issues associated with equity in MCH populations alongside considerations to continue improving MCH outcomes.

(Download)

This is the fifth in a series of five publications focused on COVID-19’s impact on maternal and child health (MCH) programs and populations in the U.S. Each publication focuses on a facet of MCH, including COVID-19 response and recovery, health and human services workforce, childcare, behavioral health, and community supports. The information contained in this series comes from a culmination of interviews and research conducted between early 2022 and January 2024, including an expert roundtable held in the summer of 2022.

Whether defined by geography, race/ethnicity, income or education, communities with different characteristics experienced the pandemic differently. Given the variety of experiences faced by different groups, engaging the wide range of impacted communities creates successful policies and programs, especially when those with decision-making power have backgrounds different from those they are engaging with. Ensuring policies and programs are adaptable is paramount to creating and sustaining equitable support services.

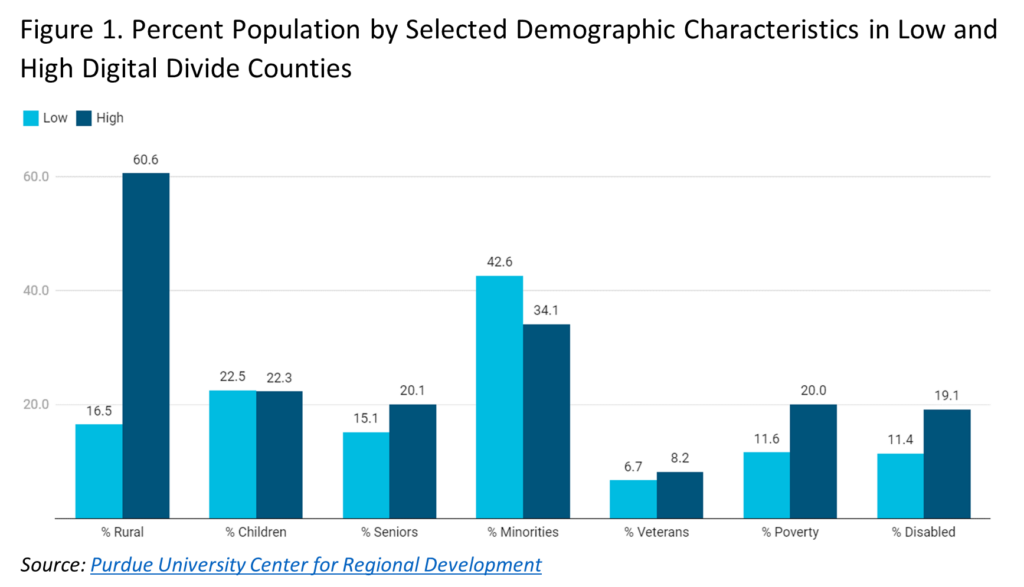

The maternal and child health population had challenges in accessing adequate care long before the pandemic—and states had challenges in the collection and reporting of data on this group—but COVID19 made these challenges more difficult. For example, the digital divide affecting access to telehealth impacted 30 percent of rural residents compared to only 2 percent of urban residents in 2019. Three years and a global pandemic later, 24 million Americans still do not have access to high-speed internet, and more lack access to the internet due to absence of broadband in their area or inability to afford services. Additionally, maternal mortality across all racial categories worsened during the pandemic, continuing decades of declining outcomes, especially among Black and American Indian and Alaskan Native (AIAN) women. In 2017, a study controlling for household incomes found broadband access across 905 major US cities in majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods was 10-15 percent lower than in majority White or Asian neighborhoods. These findings were reinforced as broadband access increased, but racial and income disparities in access persisted.[v] State leaders inherited these long-standing issues that were only heightened through the pandemic.

Governors’ Strategies

This publication explores strategies Governors and state leaders employed to address the long-standing issues associated with equity in MCH populations alongside considerations to continue improving MCH outcomes. Some of these efforts include:

Elevating equity as a primary goal in all policies through meaningful community engagement, improved data collection and culturally appropriate service options.

Leveraging existing MCH services and community-based organizations to provide outreach and education and serve as a link to additional health or social services.

- Applying for the Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grant where HRSA partners with states and judications to improve public health infrastructure to improve MCH outcomes.

Supporting data-sharing across agencies to determine actual need vs. perceived need of MCH services in areas with a disproportionate need.

Exploring options to provide broad access to telehealth and virtual social services, especially for populations living in disproportionately affected communities and in areas with limited in-person service options.

Elevating Equity as a Primary Goal in Developing Policies and Implementing Programs

The pandemic only further illustrated the need for equity and inclusion in all policies. The goal of health equity is to create opportunities for all people to attain optimal health regardless of their circumstances, including race, ethnicity, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geography, preferred language or other social factors.

Funding, diverse leadership and broad community engagement are all elements to weigh in creating equitable programs and policies. Equity considerations, especially meaningful community engagement, are vital to successful development and implementation of any policy. For example, government COVID-19 websites at all levels included details for groups requiring special considerations, whether due to their occupation, disability, age or comorbidities. Most websites had options to translate information or read it aloud; however, the information was not always translated by a native speaker or compatible with screen-reading technology. Without understanding language nuances, the text did not always translate appropriately or connect with technology designed for people who are visually impaired.

State leaders can evaluate their policies through a variety of lenses to better ascertain potential consequences. Vermont Governor Phil Scott created a Racial Equity Task Force through executive order in 2020 to promote racial, ethnic and cultural equity. This group, alongside the Vermont Office of Racial Equity and Racial Equity Advisory Panel, formed policies with the communities served. The Office of Racial Equity also produced the Equity Impact Assessment Tool to help program creators incorporate equity throughout. The Office of Racial Equity also produced the Equity Impact Assessment Tool to help program creators incorporate equity throughout. Similarly, the North Carolina Division of Public Health Women’s Health Branch and the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities partnered with NC Child, a nonprofit organization, to create the state’s Health Equity Impact Assessment Implementation Guide.

A lack of race and ethnicity data collection emerged as a long-standing issue during the COVID-19 pandemic. In July 2020, 56 percent of COVID-19 cases were not linked to race or ethnicity data. A dearth in data like this can negatively impact research initially aimed to better inform solutions and reduce disparities persisting beyond COVID-19. Race and ethnicity data is notably relevant in the ongoing efforts to improve maternal and infant mortality and morbidity as most of these deaths are incurred by Black and AIAN mothers and babies. AIAN data gaps in mortality data need to be addressed as AIAN people are classified as other racial groups between 30 to 70 percent of the time. Without proper demographic data, baseline measures are impossible to establish, affecting policies made to reduce disparities.13 States have made progress in ensuring the use of race and ethnicity data in their policies and programs. For example, former Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak signed legislation in 2021 requiring maternal mortality review committees (MMRCs) to collect and analyze race, ethnicity, age and geographic data related to the case under assessment.

In addition to the strategies outlined above, Governors may also consider:

- Prioritizing culturally appropriate messaging during outreach, implementation, operation and evaluation of new and existing programs to ensure communications resonate with the intended audience & mitigate institutional distrust.

- Involving trusted messengers and individuals that look like the community when creating and disseminating public health information, e.g., materials on safe sleep and/or tobacco cessation for pregnant women.

- Supporting and promoting caregiver engagement, including parents, mothers, fathers, foster parents, grandparents and other primary caregivers.

- Including caregivers in development and decision-making of policies and programs affecting children.

- Incentivizing providers to offer clinical or social services during non-traditional hours so both parents can attend birthing classes, ultrasounds, counseling and other services.

- Investigating the factors that contribute to health disparities among Black and Latino mothers and children and prioritizing policies and programs that enhance improved access and quality of care in such communities.

- Bringing families and community members to the table at the beginning of any program or policy-making process that would affect them by holding listening sessions, town halls, and focus groups that include voices of those with lived experience, including caregivers for children and youth with special health care needs, women of color, fathers, home visitors, doulas, community-health workers, OBGYNs and pediatricians.

Leverage Existing MCH Services and Community-Based Organizations

Pregnant and postnatal Black, Hispanic and AIAN people were more likely to experience disproportionate COVID-19 effects than other racial and ethnic groups. Community-based organizations (CBOs) are public or private not-for-profit resource hubs, trusted by their clients and their communities to provide services within that community or targeted population. Federal agencies recommend, and research has proven, that CBO partnerships with existing programs allow for essential contributions to the effective and equitable delivery of healthcare services. By integrating individualized, care-based approaches informed by CBOs, states can reduce disparities among historically marginalized communities.15 As grassroots organizations, many CBOs design their programs around their community’s needs, and local health workers provide culturally and community specific care and serve as trusted resources for their neighbors.

States and territories have MCH programs in addition to CBOs that can forge partnerships to advance equity. Through an initiative with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs, Missouri’s Department of Health and Senior Services (MoDHSS) worked to improve behavioral health outcomes for pregnant people, recently pregnant people, and infants. The state partnered with the University of Missouri-Kansas City to form the Missouri Maternal Health Multisector Action Network to promote a multidisciplinary system of care and develop a sustainable, statewide infrastructure for mothers, children and families affected by mental health conditions and substance use disorders. These efforts were a catalyst to extend postpartum Medicaid access to one year and work with Governor Mike Parson to pass an additional $4.35 million in funding to improve MCH behavioral health programs. The funding supports transformation through five domains of action:

- Standardized, evidence-based protocols for maternal-fetal health care.

- A Perinatal Health Access Collaborative to provide specialized expertise and consultation for providers to improve care for mothers and babies, particularly those at high risk.

- Strengthening the maternal health care workforce through standardized provider training on trauma-informed/responsive and culturally congruent/linguistically appropriate care and screening, referral, and treatment of mental health conditions and SUD during and after pregnancy and cardiovascular and endocrinology disorders associated with pregnancy.

- A standardized Postpartum Plan of Care to optimize comprehensive postpartum care.

- An MCH Dashboard to advance data collection, standardization, harmonization, and transparency and empower data-driven decision-making to reduce maternal and infant morbidity and mortality.

Like Missouri’s programming, other states and territories use data to inform existing MCH services and identify CBOs to implement strategies that reduce maternal morbidity or mortality. For example, in 2019 former Oregon Governor Kate Brown signed legislation to form a state-based universal home visiting program. The initiative, formalized through Oregon Health Authority administrative rules, created Family Connects Oregon to link families to existing community resources and provide free services for up to six months postpartum for all families in the state. In 2021, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed legislation providing registered nurse home visits for all mothers and newborns within two weeks of birth at no cost to the family.

In addition to the strategies outlined above, Governors may also consider:

- Leveraging wrap-around services, community-based supports and community relationships that have been utilized in other COVID-19 prevention and mitigation efforts, e.g., trusted community leaders that assisted in vaccination messaging.

- Improving access to and availability of quality home visiting services, especially for historically marginalized populations, by braiding federal, state, local and philanthropic funding.

- Partnering with community-based organizations in funding and planning to develop and operate evidence-based home visiting services.

- Exploring opportunities to pilot universally available opt-in services for home visiting.

- Addressing access and participation issues associated with government assistance programs for families.

- Encouraging WIC outreach and participation for eligible families.

- Removing administrative and other barriers to WIC, SNAP and TANF, including long wait times, poor training of grocery store clerks, availability of approved products and miscommunications.

- Supporting access to culturally responsive promising models such as family resource centers, midwifery, doula care, group prenatal care and breastfeeding support.

- Allocating Community-Based Child Abuse Prevention funds, including American Rescue Plan funds, to expand approaches such as Family Resource Centers or other family strengthening systems-building.

CBOs in Action

In Alaska, the Alaska Native Birthworkers Community offers culturally matched care to AIAN people who otherwise would not have access to services centered in Native practices and traditions. The volunteer-based program offers free services, including full circle birth helpers (doulas), childbirth educators, breastfeeding counselors, healers, caregivers, public health researchers, scholars and more alongside training and redistribution of pregnancy support items.

In Texas, Mama Sana Vibrant Woman provides culturally resonant, quality prenatal and postnatal care to Black and Hispanic mothers and families. The organization, run by a circle of care coordinators, offers services in English and Spanish to the community regardless of the ability for a patient to pay and consistently produces birth outcomes better than the national average.

In Alabama, Women’s Hope Medical Clinic partnered with Vitamin Angels in 2021 to provide women with access to prenatal vitamins at no cost. The clinic offers free supplies, single parent support groups, prenatal care and prenatal counseling. Vitamin Angels, a global organization, manufactures prenatal vitamins and offers in-kind grants to through partnerships with health care facilities serving women experiencing poverty.

Supporting Data Sharing Across Agencies

Existing state and territory data infrastructure was pushed to its limits during the pandemic as states worked to update systems, capture disease data and address the more tangible aspects of COVID-19. Ordinarily, state data is collected and siloed into various buckets often with little to no sharing across agencies or at different government levels., Bifurcated data systems prevent researchers and state health leaders from understanding the real impact policies have on communities. To create a more integrated system, former Oregon Governor Kate Brown worked with the Center for Evidence-based Policy at Oregon Health & Science University to create a dataset to improve polices for children in the state. Data collected by the Oregon Health Authority, Department of Education, Department of Human Services, Youth Authority and Integrated Client Services is used to cross- reference statistics, determine linkages and explore solutions. The dataset also depicts demographic information, including race and ethnicity, sex and gender, parent’s education level and geographic area, which allows Oregon to shape programs around impacted populations.

Data systems are updated to evolve alongside technology, collect new data points and share information in a way that represents how people live their lives. For example, Massachusetts, California, and Texas have systems to link hospital discharge and birth certificate data to accurately depict maternal and infant mortality rates., These data can help document pregnancy-related complications and couple mothers and recently pregnant people to their babies in systems going forward.28 State laws, privacy considerations, data-sharing agreements, lack of standardization and the substantial resources to reshape and maintain the systems complicate efforts to tie data together. Data linkages are especially pertinent to committees and groups that assess the quality of MCH outcomes, including MMRCs, perinatal quality collaboratives and fetal and infant mortality review groups. For example, MMRC members in 47 states and Puerto Rico can cross-reference data and records pertaining to the case to holistically assess the circumstances and determine if the death was preventable.

In addition to the strategies outlined above, Governors may also consider:

- Encouraging payers, providers, health systems, and other stakeholders to collect data on race, ethnicity, disabilities, gender identity, geographic location and other self-reported data points to establish inclusive data sets that illustrate the health of specific groups and capture intersectional challenges.

- Supporting data-sharing of maternal and child health data across agencies, departments and appropriate stakeholders

- Streamlining data-sharing processes between state government entities to reduce redundancies, improve efficiency and increase opportunities for inter-governmental collaboration.

- Coordinating referral data for social services, community-based organizations and behavioral health services to capture data on barriers to improved health outcomes.

- Encouraging cross-sector data sharing at the community level to identify and address community needs and gaps in care.

- Requiring and supporting maternal mortality review committees and perinatal quality collaboratives in collecting data on social determinants and behavioral health factors associated with maternal death in addition to health conditions and obstetric complications information.

- Coordinating maternal mortality and maternal morbidity data definitions across states to determine actual rates and create a comparable data metric.

Exploring Options to Provide Broad Access to Telehealth and Virtual Social Services

The COVID-19 pandemic expanded telehealth use and coverage. Telehealth services for general check-ups and ongoing monitoring before, during and after pregnancy can improve access by providing routine prenatal and postpartum care to patients lacking transportation or living in rural areas. For example, less than half of U.S. women living in rural areas are within a 30-minute drive from a hospital with obstetric services, and more than 10 percent drive 100 miles or more. A large disparity also exists in rural Tribal Nation lands, where about 30 percent of people living on Tribal lands do not have broadband access, compared to 14 percent living in non-Tribal areas. Telehealth also provides access to sub-specialists located hours away, increases provider choice and offers entry to prenatal and postpartum mental health services. In the area of pediatric behavioral health, telehealth has aided in addressing workforce shortages in rural and other underserved areas. The use of web-based technology, including distance-learning modalities, ensures that pediatric primary care providers and other providers who cannot participate in on-site learning sessions receive ongoing education, training, and peer-to-peer exchange. Often, pediatricians and other pediatric primary care providers (e.g., family physicians, nurse practitioners/advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants), are the first ones to identify a behavioral health condition and provide services because specialty behavioral health care can be difficult to obtain in a timely fashion. Telehealth also can allow providers to identify, assess, treat, and provide referral options for children and adolescents with behavioral health conditions more quickly and efficiently.

Recent bipartisan federal legislation, the Data Mapping to Save Moms Lives Act, seeks to identify gaps in broadband access to telehealth coverage that often results in barriers to appropriate care and correlates to negative health outcomes. States are also implementing programs to improve digital equity. In New Mexico, the Rural Obstetrics Access and Maternal Services provides telehealth to five rural counties along with home telehealth kits that automatically send medical data, like blood pressure and blood glucose levels, to the patient’s physicians. The program partners with local health and social services organizations while offering funding for patients to purchase internet service and learn to use telehealth kits. States also increased broadband access for mothers and children through reimbursement flexibilities. States have the ability to control a number of factors in regard to Medicaid eligibility, telehealth services allowed, reimbursement options, provider types, modalities to access telehealth and managed care plan governing rules. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many states implemented flexibilities in telehealth including payment and coverage parity. Many states extended policies while others made permanent changes. In Maryland, Governor Wes Moore signed legislation extending Medicaid payment parity of telehealth services through June 30, 2025. Nebraska former Governor Pete Ricketts signed the Nebraska Telehealth Act in 2021 to ensure ongoing payment parity for telehealth services.

In addition to the strategies outlined above, Governors may also consider:

- Establishing policies that allow providers to utilize telemedicine platforms for pre- and postnatal care when appropriate.

- Improving access to platforms for populations with unique needs such as non-English speakers and individuals with disabilities.

- Providing greater access to technology to provide telehealth services including clinical, home visiting, mental health and social services to more people.

- Improving broadband access to rural and under resourced areas of the state.

- Allowing telephone or “telephonic visits” to qualify as a telehealth visit and be reimbursable as such.

- Waiving the need for a pre-existing patient-provider relationship to access a provider through telehealth or receive e-prescribing of medications.

- Limiting cost-sharing for patients for telehealth visits.

- Encouraging widespread training for any provider able to see patients via telehealth to ensure the workforce can meet patient needs appropriately.

- Providing greater access to community-based and social services by providing affordable or reimbursable virtual options for behavioral health, mental health and other services.

- Allowing state and community programs to provide virtual appointment options when appropriate, such as social worker check-ins, home visiting, safe sleep training, smoking cessation programs or child passenger safety sessions.

- Providing education to non-clinical providers on legal considerations for telemedicine appointments through state agencies and departments.

STATES ACTIONS

When COVID-19 shut down normal operations in March 2020, the Louisiana Bureau of Family Health transitioned to virtual home visiting essentially overnight. The LA Bureau coordinated with the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration to develop protocols to adapt their Nurse-Family Partnership and Parents as Teachers home visiting models to deliver telehealth services through the Louisiana Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Family Support and Coaching Program (LA MIECHV).

LA MIECHV incorporated a flexible model by returning to the field in May 2022 while offering virtual services for families with less immediate critical needs. Over 70 percent of visits returned to in-person by July 2022, with home visitors and families performing a health screening to ensure the safety of both parties.

While recognizing home visiting is best conducted in-person, the virtual visits allowed flexibility for families in need of care. A 2021 Bureau survey showed 75 percent of clients agreed or strongly agreed that telehealth visits were as good as face-to-face visits.

As of May 2023, the LA Bureau provides optional virtual visits for clients, but 70 to 75 percent opt for in-person services. LA MIECHV programs require at least one in-person visit every 45 days and cannot go without an in-person visit for longer than 90 days.

Conclusion

Community engagement and equity emerged as cornerstones of policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. States and territories established partnerships to address inequities in real-time during the pandemic and set the stage for the future. Investing in data modernization and expanded broadband infrastructure became especially relevant during COVID-19 lockdowns and continue to be priorities as the country returns to more “normal” operations. With those investments and meaningful community engagement, states and territories can set forth on a path to a more modern, equitable landscape that serves residents with respect and state-of-the-art care.

Acknowledgments

The NGA Center would like to thank the state officials and experts who participated in the June 2022 expert roundtable as well as those who provided feedback to inform this publication. The NGA Center would also like to thank the Health Resources and Services Administration in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for their generous support of this project. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of HRSA or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

This publication was developed by Michelle LeBlanc, Jessica Kircher, Asia Riviere, and Brittney Roy at the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices.

Recommended citation: LeBlanc, M., Kirchner, J., Riviere, A., & Roy, B. (2024). State Strategies to Address the Impact of COVID-19 on Maternal and Child Populations: Sustaining Equitable Community Supports. Washington, D.C.: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices.