State Health Workforce Toolkit

Data and Planning

Introduction

With more than two million new healthcare jobs projected by 2031, the health sector is expected to experience the greatest new job growth of any employment sector. These new jobs, in addition to the approximately 2 million replacement jobs annually, will require intentional state, health sector, and health system planning to ensure a sufficient supply of workers in these high-demand jobs. Labor data are important, but states are also looking for additional health workforce data sources to better understand current supply and demand, support prioritization of enhancement strategies, and evaluate effectiveness of related initiatives. The information and resources in this section of the toolkit outline considerations for additional health workforce data sources and how those data may be used alone or with other data sources to better understand certain aspects of the health workforce, such as identifying shortages and assessing a state’s health workforce pipeline. Additionally, there are numerous options for how states may consider establishing a mechanism for coordinated state health workforce planning.

Inventory of Health Workforce Stakeholders

Purpose

As states take an organized approach to healthcare workforce planning, a helpful early step is generating a list of the various stakeholder perspectives. The following template can be used to identify and organize stakeholders by perspective and assist in developing a strategic stakeholder engagement strategy. Such an initiative could support coordination of related initiatives, whether informal or formalized.

Common Healthcare Workforce Stakeholder Perspectives by Role

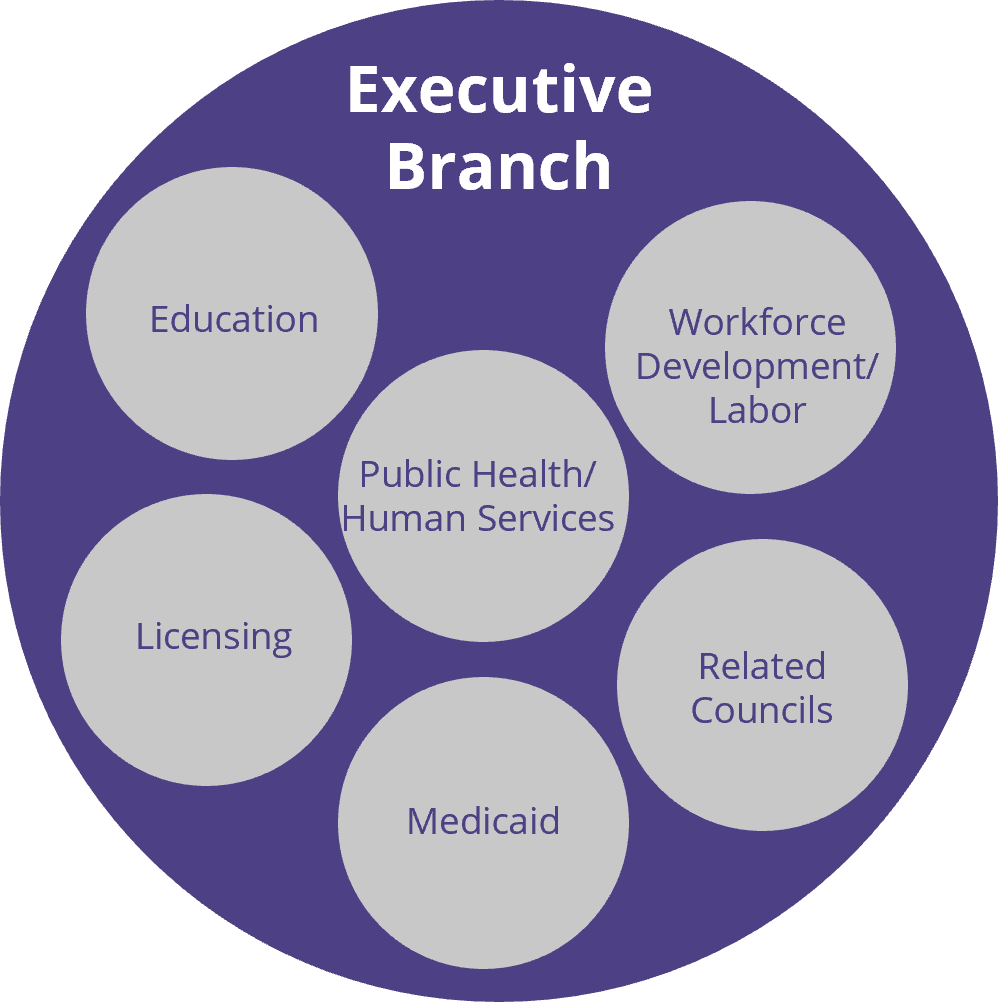

State Government - Executive Branch

| Perspective | Common Role Related to Health Workforce |

|---|---|

| Licensure boards or other entities that regulate or have jurisdiction over direct care workers |

|

| Workforce development or labor agencies and any relevant boards or committees |

|

| Departments of education, higher education, career and technical education |

|

| Public health and human services agency |

|

| Medicaid Agencies |

|

| State-based councils or forums | Some states have councils or forums related to the DCW overall or focused on special populations (such as disabilities or aging) |

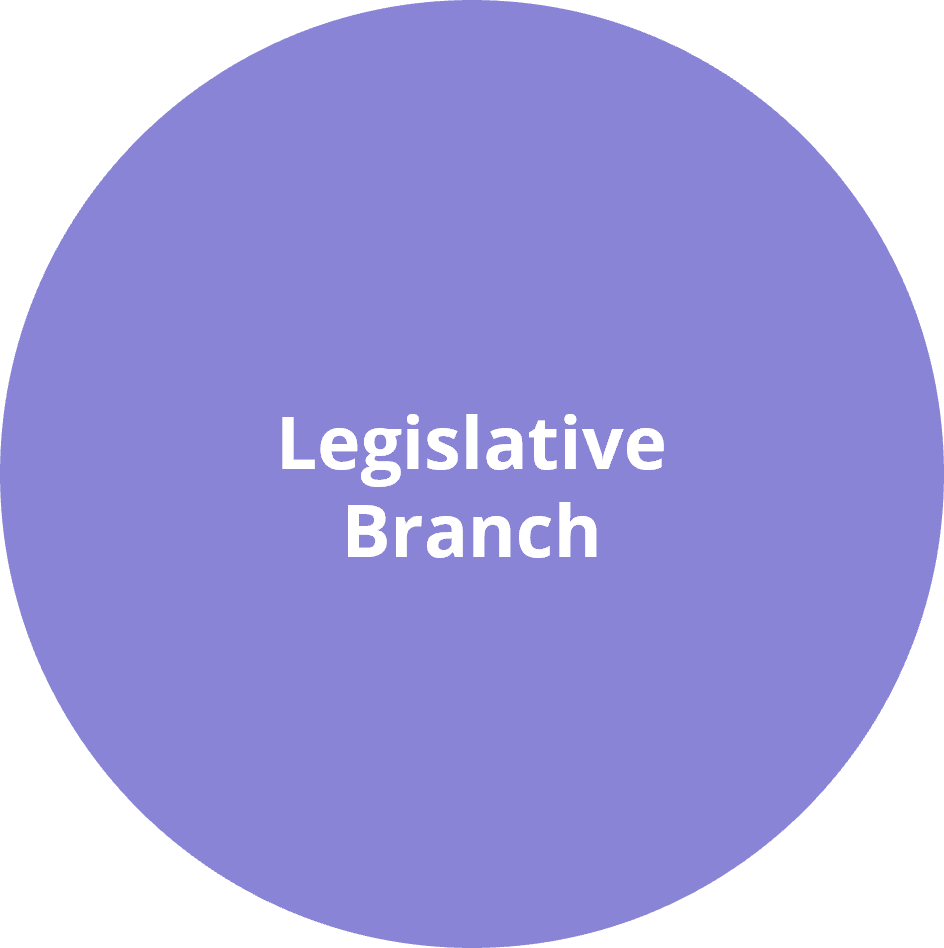

State Government - Legislative Branch

| Perspective | Common Role in DCW Conversations |

|---|---|

| Health | Legislation and oversight related to a number of areas of health care, generally including direct care occupational regulation and Medicaid. |

| Labor | Legislation and oversight related to labor, employment, workforce, economic development, etc. |

| Appropriations/Budget/Ways and Means | Considers legislation involving expenditure of state and federal funds, including developing the state’s budget with appropriations for state agencies, departments, and organizations. This likely includes any strategies related to direct care wage. |

| Education | Legislation and oversight related to education (primary, secondary and post-secondary). In some states, it oversees education related appropriations |

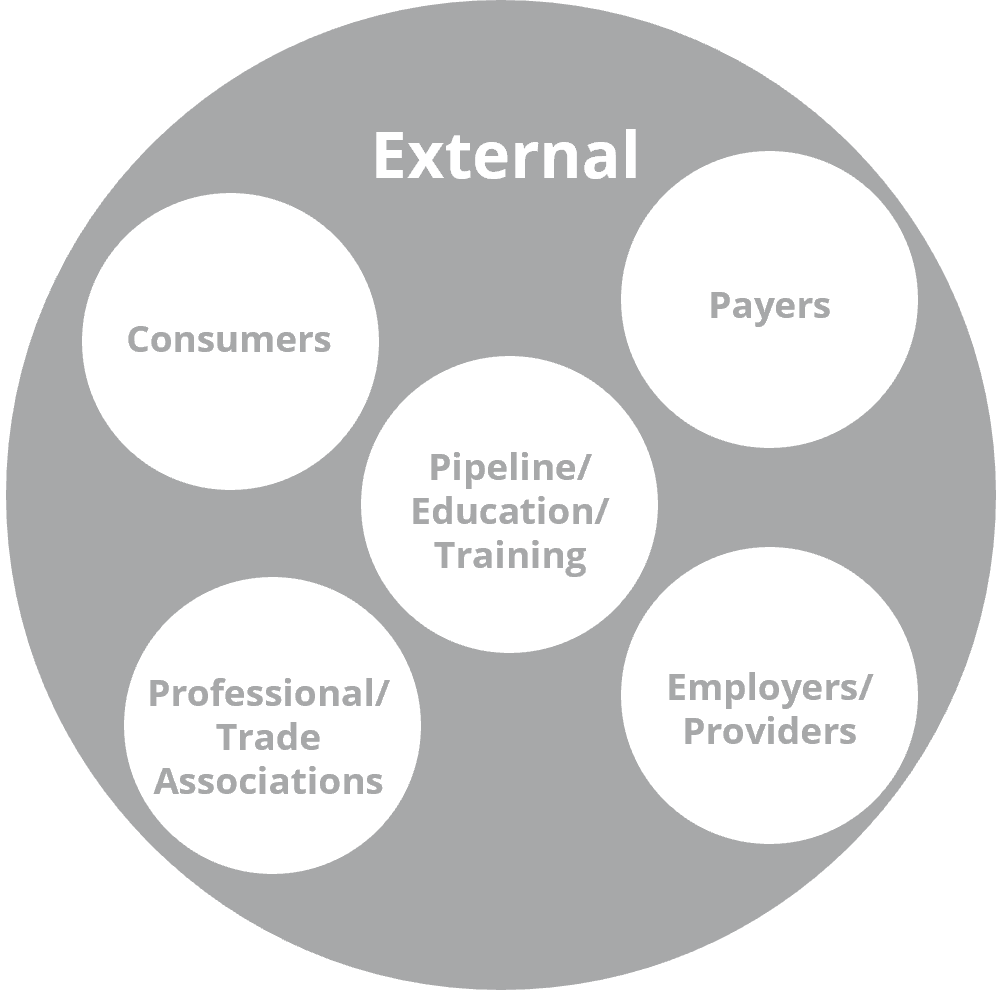

External - Key stakeholder perspectives outside of state government

| Perspective | Common Role Related to Health Workforce |

|---|---|

| Employers/Provider Organizations | Representatives of organizations/entities that directly employ or contract health care workers |

| Payers | Non-public health insurance agencies, including managed care entities |

| Consumers | Consumer advocacy organizations or public members representing the interest of patients (health care consumers). Consumer representation may vary based on sector (example: AARP may serve as a consumer representative for long-term care workforce discussions, whereas child and family organizations may serve as a representative in primary care workforce discussions) |

| Pipeline/Educators/Trainers | State level entities focused on health workforce pipeline and training, such as Area Health Education Centers, Health Occupations Students of America, career and technical education, community colleges and higher education institutions, would all fall into this category. There are opportunities for targeted engagement of external representatives from education and training entities based on the specific professions/occupations of interest (example: policy discussions regarding graduate medical education may include the perspective of residency program, while those related to direct care workers would include the career and technical education training vendors) |

| Provider Associations | Represents the perspective/interests of specific professionals/workers. Likely varies based on specific topic |

State Sources of Health Workforce Data

| Regulatory Data | Supplemental Data | Medicaid Data | Statewide Longitudinal Data System* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is it? | Information collected and maintained as part of the state regulatory processes | Additional information on personal and professional characteristics | Information collected as part Medicaid provider enrollment or reimbursement | A state data repository that links education data and workforce data. |

| How is the data collected? | Information collected in initial licensure application or renewal | Generally collected using survey tool which may be administered:

| Information collected as part of provider enrollment with health coverage programs and through claims submission process | Data are coordinated between data sets that commonly live at different executive branch agencies (such as early education, K-12, higher education, and workforce). |

| What type of information is included? | Varies by state but generally includes:

| May include:

| May include:

| SLDS generally contain aggregate and individual-level data on education metrics, outcomes, and workforce participation. |

| Benefits |

| Enables determination of workforce employed/practicing in the state and supports workforce evaluations; needs assessments and federal shortage designations |

|

|

| Limitations | Limited data. No information about employment/practice characteristics. (Not everyone who holds a license in a state practices in the state) | Requires resources to develop and implement survey | Providers may bill under group NPI numbers. Street address may be billing address as opposed to actual location where clinical service was provided | Is not generally linked to licensing or regulatory datasets. |

| Considerations | Interagency data sharing agreements should be established to meet the data needs of the state | Embedding surveys into the renewal process is optimal to maximize data and minimize cost. Structure of occupational regulation may impact how data are collected and what data can be available (ex. Census vs. sample, electronic vs. paper). Centralized administration for boards can streamline implementation and reduce costs | Interagency data sharing agreements should be established to meet the data needs of the state | Every state SLDS approach is different. Learn more about your state’s SLDS |

*SLDS or known in some states as a P-20W+

National Sources of State Health Workforce Data

| Profession | Data Source | Data Elements | How to Use | Data Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians, Dentists, Nurses | Professional Associations

| Depends on specific source | Can be accessed from respective websites | Depends on specific source, but can be found in the data methodology for each source |

| All | HRSA Health Workforce Research Centers:

| Contains various health workforce reports with analyses using secondary or primary data | Can be used to investigate a certain issue (ex: rural communities or dentists providing care to special populations) | N/A |

| Physicians, Dentists, Mental Health Professionals | State or county level information on health professional shortage areas, including HPSA score (degree of shortage) and how many FTE would be needed to relieve shortage | Can be used for geographic assessments of workforce contributions | Contains information on HPSA FTE Shortage (i.e., total number of provider FTE needed to be at sufficient capacity) | |

| Many professions | Depends on profession selected, but generally includes counts and population-to-provider rates | Can be used for comparison of similar data variables across many health professions; Includes visualization tool and downloadable files | Sourced from various secondary sources | |

| Many professions | HRSA–Bureau of Health Workforce Field Strength Dashboards | Data related HRSA health workforce development program participants. Available by year, state, program type, profession type and many other categories | Can be used to assess state program participation and compare across states | N/A |

| Many professions | HRSA–Bureau of Health Workforce Clinician Dashboards | Retention and location data of NHSC, Nurse Corps, THCGME, and CHGME alumni | Can be used to assess health professions program outcomes | N/A |

| Many professions | HRSA–Health Workforce Connector | Interactive tool allows users to search and locate open job opportunities, service sites, and training sites by a range of criteria (geography, HPSA score, clinician type) and post profiles | Access via search tool and can export files with open jobs | Includes only designated sites (Currently includes only designated NHSC, Nurse Corps, and STAR LRP sites |

| Registered Nurses, Nurse Practitioners (depending on year) | HRSA Nursing Workforce Survey Data | Demographic, education, employment and practice data | Can be downloaded from website in various formats, including forthcoming visualizations. Can be used to obtain a cross-sectional analysis of nurses in a select year or for longitudinal analyses. Some state-level information is also available | Sample survey, but represents the largest sample of RNs and NPs in the US |

| Many professions | HRSA–National Practitioner Data Bank | Includes information regarding adverse actions or medical malpractice | Can be queried via website | A practitioner may be counted in many states. Sources include: state licensure and certification actions, clinical privileges/panel membership and professional society membership actions and HHS/OIG and DEA actions |

| Many professions | HRSA–Workforce Projections Dashboard & Workforce Projections Reports | Supply and demand projections at the state and national levels | Accessible via dashboard, includes analytic supports | Methodology can be accessed via HRSA website |

| Providers with an NPI | NPI–NPPES | Includes NPI, Type, Mailing and Practice addresses, Taxonomy | Download a full dissemination file from CMS.gov | Includes NPI data for all professions, requiring extensive verification and formatting; easiest using a coding software Files are replaced monthly with updated information on NPI activation status |

| All | Bureau of Labor Statistics | Employment estimates, outlook and wage for all occupations, including oral health workers. Depending on counts, may be available by lower geographies (such as regional or county). Can be used for inter- or intra-state estimates | Can be downloaded from website | Sourced from employer surveys and as such may not be representative of solo practitioners |

| All | The NPDB’s data tool include aggregate and deidentified information regarding adverse actions and medical malpractice payments | Data tools accessible via website (https://www.npdb.hrsa.gov/). Eligible entities may query the NPDB for information about specific practitioners, providers, and suppliers. | The NPDB only includes information regarding the practitioners, providers, suppliers, and organizations that have been the subject of NPDB reports; Before downloading the PUF, requesters must agree to abide by a Data Use Agreement via the website; Sources include: state licensure and certification actions, clinical privileges/panel membership and professional society membership actions and HHS/OIG and DEA actions, as well as medical malpractice payments made on behalf of individuals. |

State Strategies for Health Workforce Assessments

Pipeline Assessments

What:

The health workforce pipeline includes training programs, both career and technical education and higher education, and other strategies (such as Health Occupation Students of America, Area Health Education Centers, Centers of Excellences, and Health Careers Opportunity Programs) that prepare people with the skills to enter the health workforce. Because many jobs in healthcare require specialized training and skills, the number of people in the health workforce pipeline has a direct impact on the number of workers who will be available. As such, states have a vested interest in monitoring the size of their health workforce pipeline (how many students are in training) and evaluating associated outcomes (how many students stay in the state and become part of the health workforce). This type of information is helpful to inform state policy and programming related to the health workforce pipeline. The following is a state strategy for assessing the health workforce pipeline.

Strategy:

Work with state career and technical, higher education or state longitudinal data systems to obtain information on pipeline size. This can be done by mapping Classification of Institutional Programming (CIP) codes to standard occupation codes (SOC) to determine the current pipeline size and/or distribution through the state. When this data is coupled with demand data (ex: Bureau of Labor Statistics or real-time posting data sources such as Burning Glass), it can be powerful to identify potential pipeline insufficiencies.

- State Example: Tennessee recently published a report, Improving the Pipeline for Tennessee’s Workforce Academic Supply for Occupational Demand Report, which includes an analysis of graduates from programs (CIP), mapped to corresponding occupations (SOC), and examines demand in context of Bureau of Labor Statistics job opening data. This report demonstrates how this could be done in many industries, including health and human services occupations (p. 47-56).

Supply Assessments

What:

Assessing the supply of health workers within a state is critical to determining workforce capacity and identifying shortages. This tool examines state strategies for health workforce supply assessment.

Strategies:

Strategy 1: Health Professional Shortage Areas and Medically Underserved Areas/Populations Designations

Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Medically Underserved Areas/Populations Designations are geographic areas/communities federally designated as having a shortage of certain health workers. HPSAs and MUA/P identified through partnership between federal and state governments. The state role involves collecting individual level data (name, profession/specialty, hours in direct patient care, practice address, etc.) on health professionals, and then using this data to either validate or update information in a federal platform used to calculate population to provider ratios and identify shortage areas. States collect individual provider data through multiple mechanisms. Some states have put strategies to collect this information from professionals at the time of their state license renewal [see "State Sources of Health Workforce Data"].

- State example: Indiana has statutory authority to collect information required for updating provider data associated with HPSAs and MUA/Ps designations at the time of license renewal for selected health professions. This strategy significantly enhances the efficiency with which Indiana can collect workforce data and identify communities with shortages of certain professionals.

Strategy 2: Population to professional/provider ratios and beyond

In order to assess health workforce supply across the state and within certain geographies, some states collect supplemental information [see "State Sources of Health Workforce Data"], including labor market/employment characteristics, practice location, specialty/roles and average weekly hours worked from licensed health professionals at the time of their license renewal.

- Population to provider ratio: Practice location information can be used to calculate population to provider ratios at the state level and within certain geographic regions (e.g., counties or catchment areas). This provides enhanced information on workforce capacity across a state but does not account for variations in hours worked or other factors that contribute to workforce capacity.

- Population to full-time equivalent (FTE) of provider ratio: Average weekly hours worked can be aggregated to a geographic unit of interest and used to estimate the full-time equivalents within a geographic area. This data can be used to calculate population to provider FTE, which may be a better indicator of workforce capacity to service the population. Population to provider FTE may provide a more accurate picture of workforce capacity. Note: In some instances, states collect supplemental information on the demographic characteristics (e.g. race, ethnicity, gender); practice setting (e.g., hospital, nursing home, etc.); services (e.g., Medication Assisted Treatment, labor and delivery, etc.) and populations served (e.g. 12-15 yrs, 65+ yrs), by a healthcare professional. When combined with the appropriate population data, this additional workforce information can support customized assessments.

Strategy 3: Medicaid provider capacity

Assuring provider capacity for enrollees is an important part of state Medicaid programming. States are required to complete a Access Review Monitoring Plan (ARMP) every three years which includes an analysis of state Medicaid provider capacity for certain services: primary care; specialty care; behavioral health, including mental health and substance use disorder; pre- and post-natal obstetric services, including labor and delivery and home health services. Provider enrollment and provider level claims may be used to assess utilization and historical capacity; however, workforce data on providers not currently enrolled in Medicaid are needed to identify and target recruitment initiatives in communities with insufficient workforce capacity for certain services (e.g., recruiting obstetric providers to enroll in Medicaid in region with shortage of obstetric service for Medicaid recipients). In addition to serving as a supply assessment, Medicaid population benchmarks (as provided by the Health Resources and Services Administration as a part of special population designations) can be used to enumerate the number of Medicaid providers necessary to satisfy unmet demand.

Demand Assessments

Strategy 1: Workforce Development Data

Monitoring workforce demand is an important function of state-level executive branch agencies for workforce development or labor. These agencies frequently collect, analyze and report data on job postings, using applications such as burning glass, to monitor trends in demand by industry and within job classifications.

Strategy 2: Health Sector Approach to Monitoring Demand

Demand for health workers changes based on the healthcare needs of the population. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that, in some instances, demand can change within a period of days/weeks. In some instances, common workforce demand monitoring tools may not provide all of the information that a state may want/need to “keep a finger on the pulse” of health workforce demand. Routinely collecting demand information from employers through structured surveys or reporting mechanisms is one way states can collect timely information on workforce demand.

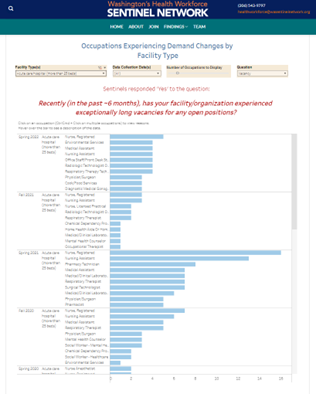

- State example: The Sentinel Network in Washington is a collaborative initiative between the Health Workforce Council of the Washington State Workforce Board and the University of Washington Center for Health Workforce Studies. This network includes a group of health sector employers that communicate their workforce needs with decision makers. The information they provide is used by the state to understand demand signals, identify skill needs and inform health workforce policy and programming.

State Health Workforce Policy Coordination Strategies

Common Leading Perspectives for State Policy Coordination

About state health workforce policy coordination: Many states have strategies in place to support state health workforce policy coordination. The way in which states formalize these strategies varies but may include: a dedicated state health workforce entity (such a center, office, commission or council); funding to support coordination activities or a formal charge through state statute or rules. States that have developed this capacity generally have supported such activities through leadership of a state agency, which is done by the agency directly or in partnership with an external entity.

Note: All information captured for the state examples were sourced from publicly available sources which are linked within the text below.

Health & Human Services

Definition: States have a significant role in health and human service functions, such as administration of Medicaid and other public sector programs, public health activities, health facility regulation, and more. States vary significantly in how health and human service activities are distributed into executive branch agencies (ex: one agency that offers all health/human service activities, or two or more agencies that fulfill distinct services). Among the states with formalized health workforce policy coordination strategies, health or human service agencies most frequently lead coordination efforts.

Benefits to this Approach:

- Under this strategy, population health is front and center.

- These agencies are commonly responsible for supporting state Health Workforce Shortage Area designation activities, which may ensure that any policy work done within this agency has a natural connection and foundation of health workforce data.

- If a state has state-based health workforce incentive programming, such as scholarships or loan repayment, , these activities are generally housed under health and human services or public health agencies. As such, broader policy coordination activities established through formal mechanisms is a natural alignment.

- Many healthcare delivery and regulatory activities are within the purview of health and human services or public health agencies, including Medicaid programming, public health activities, health facility/provider licensing, and population- or program-specific initiatives such as behavioral health or long-term care.

Considerations:

- Health and human services agencies are frequently responsible for administration of a number of policies and programs. Care must be taken to ensure the coordination is properly valued and resourced and not lost in other initiatives.

State Example:

- Georgia Board of Health Care Workforce

- Who: The Georgia Board of Health Care Workforce (Board) is a 15-member body appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the state Senate. The Board includes practitioners, health system representatives, and consumer members.

- What: The Board meets quarterly to identify health workforce needs (through production of health workforce data reports) and support development of programming to meet those needs (such as loan repayment programming or directing medical education funding).

- Mechanism of Formalization: The Board receives an appropriation from the General Assembly to execute its functions (including separate appropriations for administrative activities and funding for programming). The Board is outlined in statute and has associated rules and regulations.

- Example of Outcome: The Board produces an annual report which outlines activities completed that year, with financial reporting how funds were directed.

Occupational Regulation/Licensing

Definition: States serve a major role in occupational regulation of the health workforce. State entities responsible for health workforce occupational regulation may serve a leading role in a state’s coordination of health workforce policy and programming.

Benefits to this Approach:

- States have a major role in determining entry (prohibitions, education/training, examinations, etc.) and practice (services that can be provided and those that cannot, supervision or oversight, etc.) policies.

- Policy coordination strategies that include multiple perspectives (and represent multiple occupations) could neutralize challenging profession-specific policy discussions.

Considerations:

- States vary significantly on how occupational regulation is structured, from a centralized agency that oversees and implements all regulatory activities to a decentralized approach which relies on independent occupational boards to conduct regulatory activities. State structuring of health workforce occupational regulation should be taken into account when determining feasibility of this approach.

- Although significant, health professions’ occupational regulation is only one of the many policies related to the health workforce. Alignment with occupational regulatory entities may limit policy coordination in other spaces (ex: Medicaid, health professional shortage area activities, workforce development, etc.).

State Example:

- Virginia Board of Health Professions

- Who: The Board of Health Professions (Board) is an 18-member board that includes one representative from each of the 13 regulatory boards and has remaining citizen members.

- What: The Board is responsible for advising the Department of Health Professions, Secretary of Health and Human Resources, the Governor, and the General Assembly on matters relating to the regulation of healthcare providers, including the need for and appropriate level of regulation for currently regulated and unregulated health professions.

- Mechanism of Formalization: Statute (§ 54.1-2507:54.1-2510)

- Example of Outcome: https://www.dhp.virginia.gov/media/dhpweb/docs/studies/2020_Naturopathic.pdf

Labor/Workforce Development

Definition: States are responsible for state workforce development activities, including directing pass-through funding to support these activities and developing a state workforce plan. Some states have aligned their health workforce policy coordination activities with broader state workforce development activities to bring a labor-specific lens and see health as a workforce development industry.

Benefits to this Approach:

- States are responsible with creating a state workforce plan. States with a labor/workforce development perspective leading health workforce policy coordination activities are well-positioned to contribute to the health industry section of the state workforce plan.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics has well-established processes for supply and demand data by occupation and by industry classification. Alignment with labor/workforce development provides states with a solid data foundation to initiate health workforce policy coordination conversations and validate or provide contextual information on data findings.

- Labor/workforce development strategies (earn-and-learn programming, registered apprenticeships, up-skilling, industry credentials, etc.) have historically been siloed from traditional health workforce development strategies (such as loan repayment, scholarships, regulatory policy change, etc.). States with a labor/workforce development perspective leading health workforce conversations adds new strategies to historical health workforce development strategies.

Considerations:

- Generally, workforce development conversations prioritize high-wage, high-demand jobs with minimal entry requirements. Although these jobs do exist in the health sector (ex. Dental assistant, dental hygienist, registered nurses), there are a number of other health occupations that fall outside of these criteria. For example, some health occupations may be high-demand, lower-wage (but critically important to population health activities), such as certified nurse aides and home health aides. Other jobs may be high-wage, high-demand, but have significant education and training requirements, such as physicians, physician assistants, and behavioral health counselors. Alignment of health workforce policy coordination activities with labor/workforce development perspective, may be helpful to identify and meet the workforce needs of the state.

State Example:

- Who: The Washington Health Workforce Council (Council) is a workforce development council that reports to the state workforce board (Washington Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board).

- What: The Council is responsible for supporting the state strategic plan for supply of healthcare personnel, which is a part of the state’s overall workforce plan.

- Mechanism of Formalization: The state strategic plan for supply of healthcare personnel is a deliverable that is formalized in statute, and charged to the broad Workforce Training and Education Coordinating Board (Board). The Board then works with the Council as an industry-sector workforce development council to inform development of the plan. There are no references to the Council in statute or rules.

- Example of Outcome: The Council hosts the Washington Health Workforce Sentinel Network, which is a network of employers that regularly report real-time supply and demand information on a detailed level to inform state policy and planning. (link: https://wa.sentinelnetwork.org/findings/)