Harm reduction approaches are focused on minimizing the health, social and economic effects of drug use, including infectious disease spread and overdose with humility and compassion toward people who use drugs.

(Download)

States and communities have been working to prevent, detect and manage the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and tuberculosis (TB) for decades. In recent years, challenges have exacerbated and deterred progress toward reducing the spread of these infectious diseases. The second wave of the opioid crisis began in 2010, exacerbating substance use disorder (SUD), especially injection drug use. People who inject drugs (PWID) without access to sterile supplies have a disproportionate incidence and prevalence of HIV, viral hepatitis, STDs and TB. For example, acute hepatitis C cases rose 3.5 times between 2010 and 2016 and over 2,500 new HIV infections occur annually among PWID. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic stalled progress to improve prevention and treatment access for individuals with or at risk of contracting these diseases. Governors, state health officials and their staffs can continue their predecessors’ and constituents’ work to reduce the spread of infectious diseases while saving money and resources by investing in sustainable, accessible harm reduction programs, such as syringe services programs (SSPs).

Harm reduction approaches are focused on minimizing the health, social and economic effects of drug use, including infectious disease spread and overdose with humility and compassion toward people who use drugs. With a stigma-free aim, harm reduction often serves as a bridge for individuals to receive education about SUDs, connect with the health care system, screen for infectious diseases, obtain counseling and seek SUD treatment if they so choose. There are a wide variety of harm reduction strategies for individuals with SUD. A few common methods are highlighted in Phase 1 section and more detail is provided in the Phase 3 section. Syringe services programs (SSPs) are tailored harm reduction strategies to help PWID by meeting them in a stigma-free environment and by providing safe, sterile supplies and linkages to other health and socials services as needed.

National Harm Reduction Technical Assistance Center

The CDC and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) National Harm Reduction Technical Assistance Center (Harm Reduction TA Center) offers free help to anyone in the country providing or planning to provide harm reduction services to their community. States can access the Harm Reduction TA Center to obtain assistance from national experts in a variety of policy areas affecting harm reduction programs.

To support states and territories as they develop strategies to promote health equity and improve public health capacity to, the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) created this resource, separated into the three phases of establishing, sustaining and enhancing SSPs and other harm reduction strategies. This web page also includes a resources page, broken down by topic areas.

Phase 1: Understanding Harm Reduction

Laying the groundwork for syringe service programs

Harm reduction strategies meet people where they are mentally (and sometimes physically) by accepting people with SUD may not be ready or currently capable of stopping substance use. The purpose of harm reduction is to help individuals with SUD by preventing other health risks associated with drug use, including HIV, viral hepatitis, STD and TB transmission. Several harm reduction measures are highlighted to the right, including Syringe Service Programs (SSPs), which are tailored to persons who inject drugs (PWID). Although SSPs are evidence-based practices, many states are not set up to provide this service, whether that be for legal, funding and/or misconception of SPPs. Contrary to popular belief, SSPs do not increase crime or drug use and have evidence-based benefits, including:

- Increasing likelihood to seek treatment for SUD for new SSP clients, which might be due to increased awareness of available services

- Improving access to social programs and medication to reverse effects of opioid drugs (Naloxone)

- Providing cost-effective prevention compared to the cost of treating diseases like HIV

- Reducing HIV, hepatitis and other infection cases

Governors and state leaders interested in establishing SSPs will first need to consider barriers in their state legislation and policies and work to address those directly. State leaders should also consider conducting a vulnerability assessment to determine need and to identify potential geographic locations for services to help garner community support.

LEGAL COMPONENTS

When thinking about the legal components, state leaders interested in implementing these programs should first look to their drug paraphernalia laws. In some states, it is illegal to use, sell or deliver drug paraphernalia, which may include syringes, pipes, fentanyl test strips or other items. States have used a variety of different methods to allow SSP operation, including decriminalization of syringe possession, explicit authorization of programs in law or regulation, or completing some other approval process. Included below is a snapshot of different methods some states have used to permit SSPs. Information on other states approaches and more detailed information to be found through the Network for Public Health Law and the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

| State Law or Policy | Alaska | Georgia | Louisiana | New Mexico | Oregon | Tennessee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syringes included in state’s drug paraphernalia law | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Syringe exemption for SSP participants included in law | - | No | Yes | Yes | - | Yes |

| Prosecution protection for drug residue on returned syringes | - | No | Yes | No | No | Yes [1] |

| SSPs are allowed to operate in this state | No | Yes | Yes | Yes [2] | - | Yes |

| SSPs are not prevented from operating* | Yes | - | - | - | Yes | - |

| SSPs subject to local requirements | Yes [3] | No | Yes | - | - | Yes |

| SSPs subject to referral, service, and/or data requirements | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | Yes |

*State law does not explicitly prohibit SSP operation

[1] Participants are only able to possess syringes or other supplies while they are engaged in the exchange or going to or from the program.

[2] SSPs are explicitly authorized to operate in this state.

[3] There are no state laws prohibiting the possession or distribution of syringes, but some local communities have made it a crime.

Some states operate under “Home Rule” that adds an additional layer to the legality of SSPs. Granted through a state’s constitution or statute, Home Rule allocates autonomy to local governments. States with home rule may require approval from local government to operate a SSP in their jurisdiction, such as those outlined in the chart above. There are 32 states with Home Rule policies, many with specific requirements for SSPs operating within a city or county. For example, Florida SSPs are subject to an approval process from the county, require the county commission to authorize the program under county ordinance, have an agreement with the Department of Health, enlist the local health department to consult on the program and contract with specified entities to operate the program, such as, a health clinic or 501(c)(3) HIV organization.

FINANCING SSPs

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) allows federal funds to support SSPs under certain circumstances and does not authorize purchase of needles or syringes. HHS funding requires states to go through a determination of need process with the CDC to illustrate the state’s risk for increased HIV or hepatitis C cases. If the CDC approves the funding, states can also apply for federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grants. States use this funding along with a patchwork of other sources to support programs. In many cases, funding is from foundations, donations and merchandise sales, none of which allow for programs to operate with sustainable resources.

Buying Partnerships

In an effort to save money on supplies, some harm reduction organizations have joined together to form buyers’ clubs. A popular program is the North American Syringe Exchange Buyers Club that uses co-operative buying power to acquire the lowest harm reduction supply prices for SSPs. Similarly, the Remedy Alliance for the People has over 150 member programs to purchase bulk orders of injectable naloxone. In California, SSPs can receive supplies through the Syringe Exchange Supply Clearinghouse, which offers baseline supplies to authorized programs and create stability in program efforts.

Some states have acted to provide more reliable funding sources, including:

- California – The 2019 budget committed $15.2 million over four years to support staffing and program administration for SSPs.

- Massachusetts – Governor Charlie Baker allocated over $6.4 million for harm reduction services, including sterile and safe consumption equipment and syringe disposal services for fiscal year 2022.

- North Carolina – The state allows local funds to be used to purchase syringes, needs and other injection supplies.

Governors and state leaders may consider the following when thinking about the groundwork for setting up state SSPs:

- Legal components

- – Review existing drug paraphernalia laws and policies that impact SSP operations and consider revising to decriminalize possession and authorize access to clean supplies.

- – Revise or establish state and local laws and regulations to either explicitly or implicitly authorize SSPs.

- Funding and sustainable financing

- – Repeal funding bans or restrictions that create resource barriers to SSP operations, such as those prohibiting the use of state or local government funds to purchase syringes/needles.

- – Utilize federal funding sources to set up infrastructure for SSPs and other harm reduction programs, e.g., staff salaries, renting space, mobile vans, etc.

- – Establish specific funding streams for SSPs, such as allocating funding in the state budget as a line item.

- – Create or join a supply clearing house to bulk purchase syringes and other supplies.

- – Apply for CDC determination of need for SSPs.

NEED ASSESSMENTS

Needs assessments can help states analyze and understand the overall social and political environment as well as decide where and how SSPs can operate within a community. Health departments and other stakeholders can collect data on trends, needs and program effectiveness through initial and follow-up assessments. States should consider how they will collect data so the information they gather is meaningful and does not become a barrier to care for participants or for SSP staff. By collecting data periodically instead of daily, needs assessments can determine changing needs without burdening those who are on the ground. There are national databases that states can use, such as the CDC Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), to create their vulnerability assessment.

In 2019, the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention released the “Vulnerability Assessment for Opioid Overdoses and Bloodborne Infections Associated with Non-Sterile Injection Drug Use in Maine.” This report showed the geographic need for SSPs and led to public funding for SSP sites through the legislature and Governor.

ENGAGING PEOPLE WITH LIVED EXPERIENCE

Lived experience refers to a myriad of factors that give an individual first-hand knowledge of a specific environment or condition, such as SUD, rather than from representations constructed by others. People with lived experience can inform policies, offer new ways of looking at an issue and teach colleagues what it is like to be a beneficiary of services provided. These individuals also create a trusted environment for beneficiaries while demonstrating that recovery is possible and sustainable. Stigma and hiring practices often prevent individuals with lived experience from obtaining jobs or limit individuals to roles such as peer educators or peer recovery support services, which are vital services but not roles traditionally involved in policymaking. In addition to breaking down barriers to hiring, organizations can actively work to build culturally competent support that does not stigmatize or tokenize individuals with lived experience.

In 2010, New Mexico removed criminal history checks as screening measure for public employers to hire individuals with lived experience. Fourteen other states have similar laws, commonly referred to as fair chance hiring laws, which prohibit blanket exclusions, reduce recidivism and expand opportunities for justice-involved individuals.

Governors and state leaders may consider the following to increase understanding of the importance of harm reduction and establishing a strong framework for their state’s SSPs:

- Engage key stakeholders to develop strategies and create a safe and supportive environment for SSPs.

- Convene representatives from state and local health departments, community-based organizations, harm-reduction organizations, existing SSPs, faith communities, people with lived experience, HIV service organizations, law enforcement and others.

- Establish a messaging campaign that answers questions about the program, ensures safety and educates the community about harm reduction programs and SSPs.

- Work with stakeholders to create meaningful engagement opportunities

- – Committee/Board Membership

- – Paid Distribution Programs

- – Long-term employment

- Initiate pathways for people with lived experience to work in state and local government, especially harm reduction programs, by reviewing background check requirements for hiring.

- Provide funding for SSPs and harm reduction clinics to test for infectious diseases, such as HIV, viral hepatitis and other STDs.

- Partner with community organizations or health systems to refer clients to infectious disease care, mental health care and substance use disorder services.

- Involve PWID and people with lived experience in all aspects of program design, implementation and service delivery

- Include SSPs in public health emergency response planning to aid outbreak response activities.

Phase 2: Implementing Harm Reduction Services

Linking to care, removing barriers and increasing access

Some states and jurisdictions have policies that may impede streamlining care and creating wrap around services for people who use drugs. Governors can work with existing SSPs or other harm reduction programs focused to ensure PWID have access to linkage to care and comprehensive services by supporting policies that remove structural barriers. In doing so, harm reduction programs can prevent overdoses, mitigate infectious disease spread and improve the health of PWID. SSPs can establish other harm reduction services, including:

- HIV, viral hepatis, STD and TB testing

- Linkage to treatment for infectious diseases, mental health services or other programs (e.g., housing)

- Education about overdose and safer injection practices

- Referral and access to drug treatment programs

- Tools to prevent HIV and other infectious disease

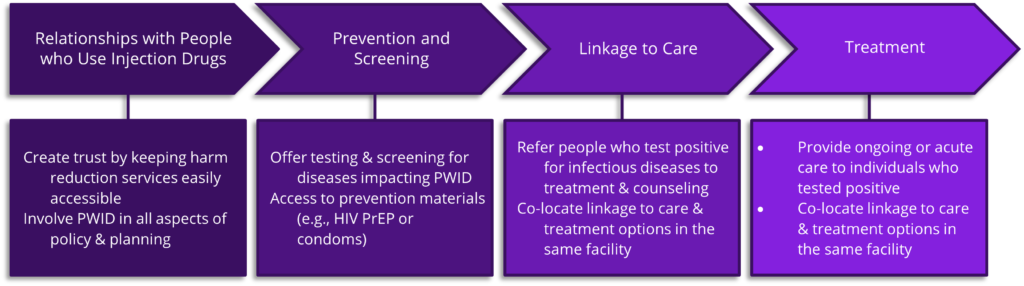

About 40 percent of new HIV infections are transmitted by people unaware of their status, and 15 percent of people with HIV have not been diagnosed. Even with awareness of their HIV status, evidence has shown that people who use drugs with HIV are six times more likely to be co-infected with hepatitis C than their HIV negative counterparts. The CDC recommends disproportionately affected individuals screen for infectious diseases such as HIV once a year; however, many PWID lack access to testing and face stigma at healthcare facilities. Harm reduction clinics can serve as a bridge for healthcare services for PWID. For example, SSPs are ideal sites for infectious disease testing and outbreak prevention as they primarily serve PWID and can repeatedly test their clients. The figure below is an adaptation of the HIV Care Continuum to reflect how harm reduction efforts can provide PWID access to medical services. SSPs can expand into other health services such as health promotion and education. Some SSPs such as Outside In in Portland, Oregon, provide linkage to primary care through a Federally Qualified Health Center. Other states, like Indiana, provide linkage to services through their local health departments. Indiana houses their division of HIV/STD and Viral Hepatitis all in one office to streamline referrals and allow for easier linkage to care.

CREATE CLEAR-CUT ACCESS TO STERILE SYRINGES

To maximize participation, states can review barriers to access, such as registration and ID requirements, literacy requirements, wait times, language barriers, and others. One way that Governors have sought to remove barriers is to allow all SSPs to have a needs-based model over a one for one exchange model (explained below). For example, during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency, Maine Governor Janet Mills signed an Executive Order removing the state’s one-for-one syringe restrictions and allowing mail-based services. Restrictions will continue to be lifted after the Public Health Emergency is over due to an amended version of legislation that allows the Maine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to engage in rule-making which would permit a syringe service provider to provide more than the number of syringes returned, subject to an overall limit to be established in the rule. The amended legislation was signed by Governor Mills and takes effect on August 8, 2022, and rule-making will proceed at that time. North Carolina, on the other hand, strictly prohibits one-for-one exchange through the state’s General Statute.

Governors and state leaders may also consider the following ideas some states have implemented:

- Prioritizing client privacy by removing government ID requirements and only requiring first names, initials or individually assigned codes such as New York’s program that creates a unique identifier during enrollment with no link to personal information

- Minimizing data collection burden on SSPs and PWID, including barcoding of syringes or collecting unnecessary participant data, which the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services advises against

- Finding unique opportunities to provide easy and efficient needle exchange such as the public health vending machines in Nevada

Needs-Based Model

- Provides individuals access to the number of syringes needed to ensure a new, sterile syringe is available for each injection

- Builds a culture of support and trust between PWID and SSP and supports secondary exchange

- Associated with lower HIV and hepatitis C cases

Mail-Based Syringe Access

Online and mail-based syringe services can be a tool to distribute supplies to populations that do not live near an SSP, as the services can remove geographic barriers and provide privacy to protect PWID against stigma. Mailing syringes is legal in the United States, but federal and state paraphernalia laws can make it difficult. By removing these legal hurdles, SSPs and harm reduction organizations can provide more people with safe sterile syringes and reduce incidence of infectious disease. The first formal mail-based harm reduction delivery program in the United States, NEXT Distro, provides free sterile injection equipment and proper disposal of syringes. NEXT Distro operates from New York and partners with SSPs across the country to provide mail in syringes in California, Louisiana, Michigan, Nevada, New York and Oklahoma.

Secondary Exchange

Secondary exchange or secondary distribution is when someone visiting an SSP obtains syringes and then distributes sterile syringes to other PWID. Some jurisdictions have discouraged or outlawed secondary exchange; however, allowing secondary exchange may help states reach a wider group of people and create peer educator opportunities. If programs do decide to engage in this model secondary distribution, there must be a minimum amount of training for PWID distributing syringes to their peers and documentation to keep the programs at a low threshold.

STABLISH PARTNERSHIPS WITH SSPS AND HEALTH DEPARTMENTS AS A MEANS OF OUTBREAK RESPONSE

Health departments play an important role in working with harm reduction services and ensuring that PWID are linked to care. Many state health departments, like in Kentucky, operate their SSPs through local health departments, but even for SSPs that are operated by community-based organizations, it is still important to have a partnership with the state health department. Additionally, SSPs can aid with infectious disease outbreak response. Through screening for infectious disease, SSPs can make health departments aware of potential outbreaks in the community. When an outbreak is detected, SPPs can provide a safe environment for delivery of prevention and care. Through cross-sector collaboration and partnerships, health departments can establish and improve statewide surveillance, coordinate funding streams and increase community awareness.

The Indiana State Department of Health created 8 short films titled “Indiana Stories in Harm Reduction” as a means to champion the important and lifesaving work from SSPs across the state. These films serve as education tools for community members.

In Kentucky, public health departments can operate SSPs after approval from relevant county boards of health, county fiscal courts and city councils. Through championing SSP policies via town hall meeting and educating officials and community members, SSP support increased in many counties. Currently, Kentucky has the highest number of SSPs in their state.

Governors and state leaders may consider the following steps states have taken to link PWID to care, remove barriers and increase access to health services:

- Advance policies that recognize the validity of syringe access and use for medical purposes, such as preventing HIV, STD and viral hepatitis infections, such as:

- – Authorizing broad syringe and needle possession;

- – Removing drug residue laws;

- – Exempting sterile injection equipment from paraphernalia policies and

- – Decriminalizing drug paraphernalia.

- – Authorizing broad syringe and needle possession;

- Create low-threshold access to sterile syringes by:

- – Providing need-based access to syringes and other injection equipment;

- – Revising policies to legalize sale of syringes through a pharmacy without a prescription;

- – Allowing for secondary distribution of syringes and

- – Continuing public health emergency-era policies to allow for needs-based access, mail-based access or home delivery.

- Collaborate with existing programs to scale up services, add additional locations or allow mobile units to access hard-to-reach areas.

- Coordinate health and social services within harm reduction programs, such as:

- – Connecting participants to nearby primary care services;

- – Providing HIV, viral hepatis, and other STD testing and linkage to care if individuals test positive;

- – Distributing harm reduction supplies such as naloxone or fentanyl test strips and

- – Integrating SUD treatment like medication for opioid use disorder.

- Develop partnerships and effective communication with the medical community, law enforcement, elected officials, business leaders, public health officials, PWID and family/friends, and the faith community to understand local needs and identify barriers and opportunities.

- Implement SSPs in established federally qualified health centers and community health centers to streamline linkage to care.

- Establish pathways for people with lived experience to work in state and local government, especially harm reduction programs.

- – Revise background check requirements for hiring.

- Partner with the state’s health department(s) and regularly conduct community and/or needs assessments or monitor epidemiological data to stay up to date on infectious disease trends or potential outbreak areas.

- Remove requirements for identifying documents to ensure anonymity of participants.

- Streamline SSP certification and registration process to remove any barriers to entry and address potential gaps in care.

Phase 3: Expanding Care

Even states with longstanding harm reduction programs can expand their scope of services to meet current needs and prevent future outbreaks. While the previous two phases focused on traditional syringe service programs, there are other innovative practices Governors can utilize to prevent the spread of infectious disease and reduce harm for both injection and non-injection drug use.

Governors can explore more upstream solutions, such as preventing the initiation of injection drug use in the first place, as well as champion a wide range of harm reduction methods to reflect current drug use trends and disease trends in the community. Governors can use their power as conveners to maintain awareness of community trends and designate actionable prevention mechanisms.

Upstream Prevention

Governors can prevent the spread of infectious diseases via injection drug use through an upstream approach by addressing underlying behavioral health factors.

- Treatment as Prevention (TasP)

- Housing First model

- Allocate resources to prevent injection initiation

- Invest in children’s mental health

- Address underlying behavioral issues

- Link people to social support before they enter SSPs

- Substance use disorder treatment as a form of HIV prevention

LAW ENFORCEMENT

Because the premise of harm reduction includes illegal drug use, successful programs require buy-in and support from public safety and law enforcement officials. Obtaining buy-in can be difficult due to stigma against PWID, poor planning on Good Samaritan Law implementation and general misunderstanding on state possession and paraphernalia laws. The variety of syringe possession and home rules give way to various type of relationships between SSPs and law enforcement. Governors can encourage law enforcement to have a more active role in promoting public health and assist in support for harm reduction and SSPs.

Positive relationships between PWID and law enforcement are critical for successful harm reduction programs. Individuals with SUD and PWID often have negative interactions with law enforcement, deterring them from engaging in SSPs or other public health and social services. Some law enforcement officials fear providing free supplies to drug users will enable drug use and worsen public safety, although research has not shown this occurring.

Governors can use their authority to address these concerns and align law enforcement agency culture with the state’s department of public health and Governor’s office. One way to address these issues and build support is for SSPs to provide or encourage regular training for law enforcement personnel on harm reduction models. For example, New Mexico partners with an outside organization to provide training for all law enforcement regarding the New Mexico Harm Reduction Act, the benefits of syringe service programs and other overdose prevention education. In addition, Good Samaritan Laws are important for preventing overdose and injury.

Although, law enforcement officials should be involved in planning and design of the implementation of Good Samaritan laws, simple training and informational tools can quickly increase law enforcement familiarity and comfort with overdose response.

Good Samaritan Laws

Some states have drug overdose Good Samaritan laws. These are intended to offer limited protections to individuals helping someone in distress or the person themselves, depending on the state’s law.

For example, Virginia’s law provides immunity for criminal prosecution to a person in possession of paraphernalia if they identity themselves, remain on the scene and offer help in good faith. In Connecticut, a person calling for help for an overdose would receive immunity for possession if there is evidence that the person was helping in good faith.

Once rapport has been built between harm reduction entities and law enforcement, law enforcement can have a more active partnership in ensuring people who use drugs do not enter the criminal justice system and instead receive social support. For example, Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), also known as Let Everyone Advance with Dignity, is a criminal justice reform approach allowing law enforcement officers to be a point of contact to divert individuals into harm reduction interventions, rather than into the cycle of the criminal justice system. In Hawai‘i, LEAD identifies people who are in high contact with law enforcement for issues related to public health and offers them services. In addition, LEAD Honolulu’s 2-year evaluation found that clients’ greatest need is permanent housing, and clients reported a 53 percent decrease in emergency shelters and a 46 percent increase in transitional shelters as a result of receiving housing through the program. While the program only saw a slight decrease in substance use, the state expects that meeting other social needs such as housing and behavioral health will trickle down to decreasing harm from substance use, including overdose and infectious disease. Success with this program required close collaboration with the local police department and the prosecutor’s office. However, when those two entities were unable to align their support for the program, Hawai‘i Health & Harm Reduction Center (HHHRC) found that social contact referrals and working closely with the Community Outreach Court have been effective. Harm reduction entities in Hawai‘i continue efforts to collaborate with law enforcement. Hawai‘i law recommends that law enforcement representatives are part of the syringe exchange oversight committee. In addition, police officers can also have a more active role in promoting public health by carrying naloxone. An observational study in Ohio found that in areas where more law enforcement officers are trained and carrying naloxone, there is an associated reduction of opioid overdose deaths.

OTHER FORMS OF HARM REDUCTION

There are many ways states can reduce harm for people who use drugs based on the current needs of their residents. Drug use trends are subject to change, and the definition of harm reduction may have to adapt. For example, San Francisco, California saw a transition from injecting opioids to smoking fentanyl, and Washington state saw an uptick in cocaine between 2018 and 2020. Though SSPs focus on preventing blood-borne infectious disease, some jurisdictions are also seeking to provide safer supplies for drug ingestion with a goal of preventing infectious disease by reducing the number of injection incidents and increasing personal protective behaviors. Additionally, providing safer supplies for ingestion may get more drug users into the doors of SSPs and increase access to the behavioral interventions they offer. For example, one study found that SSP participants are more likely to use a condom than non-participant drug users. Exploring other harm reduction mechanisms may require states to overcome legal barriers. While there are numerous resources available on SSP laws and possession laws, there are little to no resources available about other forms of harm reduction. The chart below summarizes relevant harm reduction tools and policy levers states have explored.

Overdose Prevention Centers

Overdose prevention centers (OPC), also known as supervised consumption sites or supervised injection sites, are a sanctioned, safe space for people to consume pre-obtained drugs in a controlled setting under the supervision of trained staff with access to sterile injection equipment and tools to check drugs for fentanyl. Many OPC operate in Europe and Canada, but U.S. jurisdictions are also implementing centers in their communities. Currently, the only publicly recognized OPCs are located in New York City, co-located within OnPoint’s existing SSP. In the first three weeks of operation, OnPoint NYC averted at least 59 overdoses to prevent injury, and death and the center has been used more than 2000 times.

The Controlled Substances Act “crack-house” statute created legal barriers to implementing OPCs. States and governments can introduce legislation to implement OPCs as pilot programs, such as was done in Rhode Island. Other jurisdictions are also working to sanction their own OPC, such as in Philadelphia and San Francisco, but have been facing legal challenges.

STATE HARM REDUCTION TOOL EXAMPLES

| Harm Reduction Tool | Description | Policy Levers | States Using This Tool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fentanyl Test Strips (FTS) or Drug Checking |

|

|

|

| Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) | A combination of medications (buprenorphine, methadone and naltrexone) that target the brain aimed to improve treatment outcomes |

|

|

| Naloxone | A medicine that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose. It should be given to any person who shows signs of an overdose or when an overdose is suspected |

|

|

| Overdose Prevention Centers (OPC) |

|

|

|

| Safer Inhalation Supplies | Sometimes called "safer smoking kits," these can provide people who inject drugs an alternative to injecting to reduce the spread of infectious diseases. Kits may include glass stems and pipes used to inhale smoke or vapors, plastic mouthpieces to prevent lip burns, and items to insert or hold the drug in place such as screens, wire, and wooden push stick. | Legislation or guidance authorizing the distribution of supplies by public health authorities |

|

| Syringe Services Program (SSPs) | CDC defines SPPs as community-based prevention programs that can provide a range of services, including linkage to substance use disorder treatment; access to and disposal of sterile syringes and injection equipment and vaccination, testing, and linkage to care and treatment for infectious diseases |

| As of January 2022, 43 states, DC and Puerto Rico have a SSP |

| Wound care |

| Legislation or guidance providing these supplies (no policy barriers to implementing wound care) | All states and territories |

Disclaimer: This is not an exhaustive list. Other forms of harm reduction include condoms, testing, PrEP, etc. This chart was developed in March 2022, and state legality is subject to change.

Resources

Toolkits and Resource Centers

Division of HIV & STD Programs Syringe Services Program Guidelines | Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

- Guidance for local and state health department including direction for implementation, operation and evaluation of SSPs. (2018)

A Guide to Establishing Syringe Services Programs in Rural, At-Risk Areas |Comer Family Foundation

- Resource offering background information and key recommendations specific to vulnerable areas, including state examples, FAQs and additional resources. (2019)

Harm Reduction Resource Center | National Harm Reduction Coalition

- Up-to-date resource library broken down by issue area with fact sheets, webinars, manuals, training guides and more.

The Implementation of Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) in Indiana: Benefits, Barriers, and Best Practices |Indiana University Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health

- Report outlining the public health benefits associated with SSPs, best practices of effective SSP implementation, as well as barriers associated with implementing an SSP. (2018)

Model Syringe Services Program Act | Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association

- Template for legislative act authorizing the establishment of comprehensive syringe services programs.

Overdose Response and Linkage to Care: A Roadmap for Health Departments | National Council for Mental Wellbeing

- Roadmap providing local and state health departments with information, resources and tools to implement effective strategies to support linking people who are at risk of opioid overdose to care.

SSP Nationwide Directory | North American Syringe Exchange Network (NASEN)

- Nationwide map of operational SSPs with their exchange policy and contact information.

Syringe Services Programs (SSPs) | CDC

- Website dedicated to SSPs, with links to additional resources such as an SSP fact sheet, SSP FAQs, SSP infographics and a summary of information on the safety and effectiveness of SSPs.

Funding

Buyers Club Application | NASEN

- The Buyers Club uses co-op buying power to order supplies and acquire the lowest syringe prices for large and small exchange programs alike.

Federal Funding for Syringe Services Programs | CDC

- Website including guidance, summaries and resources regarding federally financing SSPs. (2019)

Federal Funding for Syringe Services Programs | AIDS United

- Fact sheet on federal funding information for community-based organizations. (2021)

Federal Restrictions on Funding for Syringe Services Programs | Network for Public Health Law

- Provides a summary of legal barriers for states to fund SSPs. (2021)

Funding for Syringe Services Programs | Rural Community Toolbox

- Search tool to find funding opportunity to support SSPs.

SSP Grant Applications | Comer Family Foundation

- Grant application available for 501(c)(3) SSP programs. Applications are accepted on May 1 and on November 1 of each calendar year.

Technical Assistance and Training

Basics of Wound Care | National Harm Reduction Coalition

- Two-hour virtual training will cover the basics of wound care commonly needed while working at an SSP.

Guide to Developing and Managing Syringe Access Programs | National Harm Reduction Coalition

- Manual is designed to outline the process of developing and starting a Syringe Access Program. It offers practice suggestions and considerations rooted in harm reduction. (2020)

Harm Reduction is Health Care Training Guide | National Harm Reduction Coalition

- Interactive toolkit focused on understanding harm reduction practices as a component of the health care system with an emphasis on funding. Includes a 90-minute course and free workbooks and resources. (2021)

Harm Reduction is Part of the Treatment Continuum | New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports (OASAS)

- Training discusses normalizing SUD through patient-centered care to improve outcomes and reduce overdose deaths. (2021)

National Harm Reduction Technical Assistance Center | CDC and SAMHSA

- Website designed to strengthen the capacity and improve the performance of SSPs and other harm reduction efforts. Includes resources, FAQs and ability to directly request technical assistance.

Syringe Service Program (SSP) Protocol | New Mexico Department of Health

- Document providing specific protocol for implementing and incorporating syringe services into the spectrum of prevention health services for the state. (2019)

Technical Assistance & Operational Support | National Harm Reduction Coalition

- Website with direct links to ask questions about harm reduction and request assistance.

Workforce Issues

Behavioral Health Workforce Resource Center | University of Michigan School of Public Health

- Website with vast array of projects, publications, data and trainings developed specifically on building a stronger behavioral health workforce.

Guidelines for Partnering with People with Lived and Living Experience of Substance Use and Their Families and Friends | Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction

- Document provides guidance for working with people with lived and living experience of substance use and their peers. (2021)

Harm Reduction at Work | Open Society Public Health Program

- Guide outlining the benefits of hiring drug users with realistic advice on how to overcome obstacles of hiring drug users, including those with HIV or hepatitis C. (2011)

Recovery Support | HHS Overdose Prevention Strategy

- Webpage highlighting current federal activities that improve recovery support by developing different types of care throughout the lifespan, increasing the quality of services, supporting the recovery workforce and expanding access to ongoing, affordable and effective services.

State Strategies to Increase Diversity in the Behavioral Health Workforce | National Academy for State Health Policy

- Brief exploring existing state strategies that target increasing engagement of Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) across the behavioral health workforce. (2021)

Law Enforcement and Legal Components

Building Successful Partnerships between Law Enforcement and Public Health Agencies to Address Opioid Use | Police Executive Research Forum

- Resource highlighting promising models on collaborative efforts between law enforcement and public health to provide guidance to jurisdictions on how to develop and implement their programs. (2016)

Dillon Rule and Home Rule: Principles of Local Governance | Legislative Research Office – Nebraska Legislature

- Brief explaining the difference in Dillion Rule and Home Rule and the variations in which states operate both legal elements. (2020)

Engaging Law Enforcement in Harm Reduction Programs for People Who Inject Drugs | Ontario HIV Treatment Network

- Resource including evidence-based methods with specific examples, such as utilizing police discretion to redirect individuals to appropriate services and methods to support collaboration between public health and law enforcement. (2016)

Harm Reduction Laws in the United States | The Network for Public Health law

- Document containing plain language explanations of laws related to harm reduction in each state. (2020)

Police & Harm Reduction | Open Society Foundations

- Report showcasing alternatives to common punitive models for policing and recommendations for how to incorporate new, evidence-based harm reduction approaches that aim to increase public safety, public health and public confidence. (2018)

Infectious Disease Prevention and SUD

Addressing the Rise of Infectious Disease Related to Injection Drug Use |NGA

- NGA Center case study on Kentucky, highlighting the state’s approach in expanding comprehensive harm reduction. Includes considerations for other states and Governors. (2019)

Evidence-Based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States | CDC

- Document to assist community leaders, local and regional organizers, non-profit groups, law enforcement, public health and members of the

public in understanding and navigating effective strategies to prevent opioid overdose in their communities.

Have the Conversation: Caring for People Who Inject Drugs | New Hampshire Harm Reduction Coalition

- Guide for health care providers offering specific language and questions to help engage and connect PWID with care. (2017)

HIV and Substance Use | CDC

- CDC’s overview risk factors, prevention challenges and CDC initiatives to address HIV and drug use through high-impact prevention. (2021)

The Intersection of Hepatitis, HIV and the Opioid Crisis: The Need for a Comprehensive Response |NASTAD

- A NASTAD issue brief outlining best practices around harm reduction efforts, preventative efforts for hepatitis and HIV and access to care. (2018)

People Who Use or Inject Drugs and Viral Hepatitis | CDC

- Resource includes guidelines, recommendations, resources and free communication materials.

State Approaches to Addressing the Infectious Disease Consequences of the Opioid Epidemic | NGA

- NGA Center issue brief exploring insights from states engaged in an NGA Learning Lab focused on the intersection of the opioid epidemic and infectious disease. (2019)

Acknowledgements

The National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) would like to thank the state officials and other experts who offered insights that informed this publication. A special thank you goes to the participants in the NGA Center expert roundtable on Supporting and Sustaining Access to Harm Reduction Services for People with Substance Use Disorder.

The NGA Center would also like to thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for their generous support of the expert roundtable and this publication under this cooperative agreement. This web resource is part of a project funded by the CDC National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

This publication was developed by NGA Center for Best Practices Senior Policy Analyst, Michelle LeBlanc; Policy Analyst, Myra Masood; Program Director Brittney Roy. The authors would like to acknowledge contributions by CDC Public Health Associate, Eden Moore for their assistance in compiling this publication.