This document serves as a reference guide to demonstrate how Governors are thinking about infrastructure investments holistically, organizing their administrations to yield success, building partnerships to leverage funding and financing, navigating and improving the procurement process and building a legacy of accomplishment and customer service.

(Download)

Executive Summary

As America begins to rebuild its aging infrastructure, Governors will be responsible for investing billions of dollars into their local roads, bridges, transit, port, airport, water, sewer and broadband systems. In addition to raising and investing local revenues, states and territories are the indispensable conduit for federal funds, including coronavirus relief funds and the generational investment through the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).

America’s Governors are positioned to make massive impacts in their states and territories. State and territory administrations, benefitting from proximity to the public they serve as well as vast institutional expertise, are well suited for the task at hand.

This document serves as a reference guide to demonstrate how Governors are thinking about infrastructure investments holistically, organizing their administrations to yield success, building partnerships to leverage funding and financing, navigating and improving the procurement process and building a legacy of accomplishment and customer service.

The paper sets out multiple best practice examples from across the United States and other jurisdictions and provides best practice observations from, and for, Governors, their staff and their agencies.

Governors’ Leading on Infrastructure Initiatives and Major Projects

- Infrastructure investments are critical to the health of a state’s economy and the quality of life of its residents. Governors have shown tremendous leadership in championing the importance of investing in infrastructure projects for the benefit of the state’s economy and its communities. Many Governors have implemented statewide infrastructure programs along with system and region-shaping megaprojects while taking a holistic view of infrastructure investments and considering the broader implications of investments on the state and public.

Setting Up For Success

- Governors are establishing teams within state government dedicated to shepherding major infrastructure investments. Major infrastructure projects are herculean undertakings, which involve partnerships between multiple state agencies, the private sector, local government stakeholders, other states and the federal government. Governors have adopted a variety of approaches to achieve success with complex projects and programs.

Building Partnerships to Get the Job Done

- Delivering big infrastructure requires a comprehensive, all-hands-on-deck approach working strategically with federal and local governments, the private sector, and other key constituencies. States have implemented myriad funding, financing and partnership mechanisms that can come together to form a solid infrastructure foundation.

Navigating and Driving Procurement For Results

- Increasingly, states have been adopting innovative procurement methods to promote value for their communities. Governors are looking at the whole of “infrastructure” as a portfolio of assets to manage, maintain and invest in. As states move to incorporate new priorities and broader community renewal and enhancement goals into projects and investments, they are making these outcomes part of the procurement process and reinforcing those goals throughout the life of the project. The strategic partnerships in which Governors are investing often result in an open and clear dialogue that prioritizes the ultimate goals in the discussion. Unsurprisingly sometimes the state will have the tools and expertise at hand, other times the private partners will bring solutions to the table.

Demonstrating Value

- While infrastructure forms the essential foundation of our daily lives, most Americans do not typically pay close attention to the planning, development and operations of these crucial systems and the benefits that they provide. Many states have adopted innovative ways to tell a story about their progress in infrastructure improvements. The initiatives and examples contained in this paper ultimately call positive attention to the good work being done by state agencies that are providing exceptional services to individuals through their hard-earned tax dollars. Storytelling that calls attention to the tangible, everyday benefits of infrastructure improvements can drive support for further investment and lay the foundation for a Governor’s legacy of success.

- The best infrastructure investments are done in a way that looks easy, or that the public barely notices at all. At the same time, disinvestment or non-functioning infrastructure can have disastrous and very public consequences.

Governors, and their administrations, are making historic investments in their communities and regions. As they lead on implementation of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Governors are laying the foundation for success across America and positioning the nation for a new era of global competitiveness.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

As America begins to rebuild its aging infrastructure, Governors will be responsible for investing billions of dollars into their local roads, bridges, transit, port, airport, water, sewer and broadband systems. In addition to raising local revenues, states and territories are the indispensable conduit for federal funds, including coronavirus relief funds and the generational investment made possible by passage of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).

While many in the transportation, water and sewer sectors have seen large-scale mobilization before in the form of “shovel-ready” investment from the federal government (think about the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act), the needs, goals and priorities of today-particularly those of focus by the Biden Administration-are more complex and represent a change in direction from previous policies, along with a focus on a more resilient future.”

The imperative for today’s investments is clear: the poor condition of America’s infrastructure has been detailed for over 20 years in the American Society of Civil Engineers’ quadrennial Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, and the American public consistently supports the notion of increased investment in the infrastructure systems they use every day. The impact of deteriorating infrastructure is pervasive throughout the country, felt in both urban and rural communities alike. With the recent passage of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the potential for transformative change is equally enormous.

America’s Governors are positioned to make massive impacts in their states and territories as a result of these investments. State and territory administrations—at once benefitting from close proximity to the public they serve as well as vast institutional expertise—are well prepared for the task at hand. And partnerships with key stakeholders, federal and local governments, and the private sector, will be critical to success. In recent years, many Governors have made major infrastructure investments, from new airport terminals and transit lines to congestion-alleviating highway projects, benefitting local, regional and national economies for decades or longer.

This guide examines successful projects and initiatives from an array of major infrastructure investments demonstrating how Governors are utilizing best practices to advance major infrastructure investments quickly and efficiently. It shows how Governors have achieved successes for the near and long term, and how they have demonstrated those successes to diverse constituencies.

It also looks at the power of strategic partnerships that drive investment in key infrastructure assets, and the importance of viewing a state’s infrastructure portfolio as a strategic and indispensable state asset, which can serve to achieve larger goals and priorities.

Chapter 2 – Governors Leading on Infrastructure Initiatives and Major Projects

Governors have shown tremendous leadership in championing the importance of investing in infrastructure projects and doing so holistically. At the start of 2022, Governors set out ambitious agendas in their annual State of the State addresses, with many proposing continued investments in major infrastructure projects and initiatives to support their communities. This chapter provides just a few examples of the many ways Governors are leading on infrastructure, including through statewide infrastructure programs and system and region-shaping megaprojects.

Initiatives to Improve Statewide Infrastructure

Building Idaho’s Future is Idaho Governor Brad Little’s plan to utilize Idaho’s record budget surplus to provide tax relief and make strategic investments in transportation, education, broadband, water capital construction and other critical areas. Combining one-time and continued investments with targeted tax relief, the Building Idaho’s Future plan looks to make long-lasting impacts that benefit the lives of Idahoans. The plan invests $126 million in one-time funds for state and local highway projects and makes targeted investments in safe routes to schools, rail infrastructure and community airports. The plan allocates $80 million dollars in new ongoing transportation funding; a measure signed into law by Gov. Little on May 10, 2021. Funding is also provided in the plan towards the expansion of broadband in the state, the promotion of clean water, and investments in workforce development and education.

Alabama Governor Kay Ivey has made broadband expansion a top priority. By engaging critical internet service provider stakeholders, Alabama led on the creation of the Alabama Broadband Map. According to the Governor’s office, the map utilizes address-level data to better determine eligibility for state and federal broadband investment to connect unserved areas; facilitate ISPs expansion planning efforts; and provide a more accurate depiction of broadband, including speeds and technology, in each census block of the state. In announcing the plan as a part of Alabama’s comprehensive Alabama Connectivity Plan, Governor Ivey stated that “Expanding access to high-speed internet will help bring more jobs, improve educational opportunities and bolster our economy. I commend ADECA, the internet service providers and all others involved in this mammoth effort to create this valuable new tool that will enhance our efforts to provide broadband services to every corner of Alabama.”

On the transportation side, in 2019 Governor Ivey announced, and the legislature overwhelmingly passed, the Rebuild Alabama Infrastructure Plan, which committed to rebuilding the state’s transportation infrastructure with a 10-cent fuel tax increase phased in over three years, with an adjustment to track with the National Highway Construction Cost Index. The funds are being used for transportation infrastructure improvement, preservation and maintenance projects. A separate allocation of the revenues is dedicated to paying a bond to finance improvements to the shipping channel, which provides access to the facilities of the Alabama State Docks. The plan also sets aside $10 million annually for local projects through the Rebuild Alabama Annual Grant Program. In 2020, this program awarded $10.2 million to local projects, and in 2021, an additional $10.1 million was allocated to over 40 road and bridge projects across 35 cities and counties in the state. At the announcement of the Rebuild Alabama Plan in 2019, Gov. Ivey said, “After 27 years of stagnation, adequate funding is imperative to fixing our many roads and bridges in dire need of repair. By increasing our investment in infrastructure, we are also making a direct investment in public safety, economic development, and the prosperity of our state.”

California’s Senate Bill 1, the Road Repair and Accountability Act, was originally passed in 2017 and later reaffirmed by a ballot initiative in November 2018. This initiative provides approximately $5.2 billion per year in increased transportation revenue into a dedicated State Transportation Fund, through a 12 cents per gallon increase in gasoline excise taxes, a 20 cent per gallon increase in diesel excise taxes, a 4% increase in the diesel state sales tax, and additional registration fees. These increases were coupled with an annual inflationary adjustment, however, Governor Gavin Newsom suggested in his March 2022 state of the state address that he is considering a pause in the gas tax increase and other measures to address rising prices. About half of the revenue is allocated to a “Fix it First” program for deferred maintenance projects on state highways, bridges, culverts, and drainage. The other half is dedicated to repairing local streets and roads, improving transit, enhancing trade corridor routes and towards active transportation facilities. The state maintains the website, rebuildingca.ca.gov to provide transparency to the public on which projects are being funded by the initiative and the benefits being delivered (see Chapter 6).

Governor Newsom has built on this initiative through executive orders signed in 2019 and 2020 targeted at reducing greenhouse gas emissions in transportation, which account for more than 40% of all emissions in California, to reach the state’s ambitious climate goals. In March 2021, the California Department of Transportation (CalTrans) released the Climate Action Plan for Transportation Infrastructure. This outlined key investment strategies for investing billions of discretionary transportation dollars annually to combat and adapt to climate change, while supporting public health, safety, and equity. Former California State Transportation Agency Secretary David Kim framed the Climate Action Plan approach as a multi-agency collaborative effort “designed to be a holistic framework for aligning state transportation investments with the state’s climate, health, and social equity goals.” Indeed, the plan demonstrates the wide array of Governors’ priorities that can be addressed with a strategic and collaborative approach to investing in infrastructure.

PARTNERSHIPS WITH INDUSTRY

“With more projects moving into the pipeline, the Illinois Department of Transportation is also redoubling its efforts to boost inclusivity through the Disadvantaged Business Enterprise program. That means strengthening programs that provide opportunities to get young people started on a career in transportation and make more small businesses eligible to participate in projects. This will help create jobs, grow businesses, and ultimately make the capital bill project selection process more competitive.” — Illinois Transportation Secretary Omer Osman

In 2019, Illinois passed Governor JB Pritzker’s Rebuild Illinois initiative, a $45 billion, six-year capital plan. Rebuild Illinois makes critical investments in the areas of transportation, education, state facilities, environment/conservation, broadband deployment, healthcare, human services and economic and community development. The initiative is funded through a range of measures, including an increase in the motor fuel tax per gallon from 19 cents per gallon to 38 cents (indexed to inflation via the Consumer Price Index), a 5 cents per gallon increase in the special fuel tax (on diesel fuel, liquified natural gas or propane), increases in title registration fees and vehicle registration fees, and a redistribution of sales tax on motor fuel purchases. Under Rebuild Illinois, revenues from the increase in the state gas tax are assigned to a new Transportation Renewal Fund, which invests in local and state road, bridge and mass transit infrastructure improvements. In his 2022 State of the State address, Governor Pritzker lauded the benefits of this program in building roads and bridges across state, but suggested a freeze on the gas tax increase for the coming fiscal year to help provide relief from rising gas prices.

As Illinois Department of Transportation Secretary Omer Osman said in 2019, “Because of Gov. Pritzker’s leadership and the General Assembly’s bipartisan support of transportation, [the] Illinois Department of Transportation is back in the business of building a premier transportation network that creates jobs and improves quality of life.” This is a keen observation that sums up a simple formula for directly improving people’s lives—strong Governor support for improving the infrastructure constituents need, want and use the most.

Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer was elected to office in 2018 after running on a platform to “fix the damn roads.” Citing the state as being home to “some of the worst roads in the nation,” and making the case that without action, the system was on course for significant additional deterioration, Gov. Whitmer initially went to the Michigan legislature with a budget plan to increase the state motor fuel tax to yield $2.5 billion in revenues to invest in the system. While the Michigan legislature ultimately did not approve increasing the motor fuel tax to pay for the plan, the Governor utilized administrative actions to issue state road bonds to provide an additional $3.5 billion in road funding to add and expand 122 major new road projects and nearly double the amount available to fix roads over five years. Progress on Gov. Whitmer’s Rebuilding Michigan Program is highlighted on a public website that tracks road and bridge progress, major projects, jobs supported, and hours worked on the program.

Additionally, in October 2020, Gov. Whitmer announced the Michigan Clean Water Plan, which proposed $500 million to help local municipalities upgrade drinking water, source water and wastewater infrastructure. Capitalizing on a variety of funding sources to address diverse needs, the Michigan Clean Water Plan aligns “$500 million in federal dollars, state bonding authority, and existing/prospective state revenues into a comprehensive water infrastructure package” to create jobs, support overall public health, and improve environmental quality. Since the release of the plan in 2020, the Governor has announced several expansions to the program. This includes $200 million to replace lead service lines statewide by using federal dollars under the American Rescue Plan, and an additional $300 million to support local communities in addressing lead in drinking water; to provide technical, managerial and financial support to localities; and to transition homeowners, schools, daycares and others from contaminated wells to safe drinking water systems.

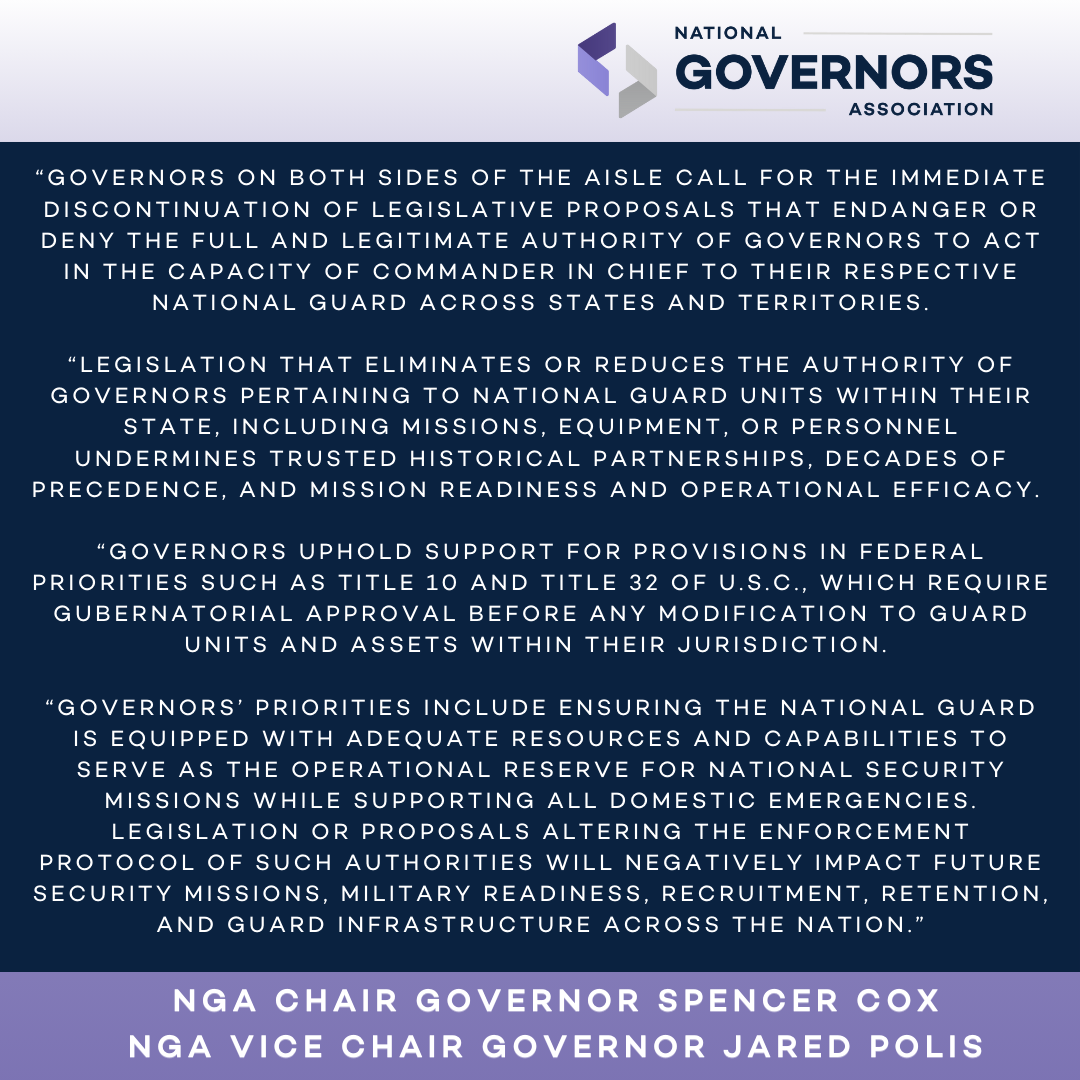

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan and Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer worked in the leadup to passage of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to advocate for passage of the law and include Governors’ priorities. The Governors testified in 2020 to the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee and led conversations with key federal officials to discuss implementing the legislation at NGA’s 2022 Winter Meeting.

Megaprojects Linking Systems and Regions

Network Improving Megaprojects in Maryland

In Maryland, Governor and 2019-2020 NGA Chair Larry Hogan has consistently emphasized infrastructure as both a catalyst for revitalizing the state’s economy and a national imperative, through his NGA 2019-2020 Chair’s Initiative Infrastructure: Foundation for Success. While initially moving forward with nearly all top priority projects proposed by Maryland’s local governments, the Governor turned attention toward advancing megaprojects that would have a direct impact on Maryland’s economy and regional competitiveness.

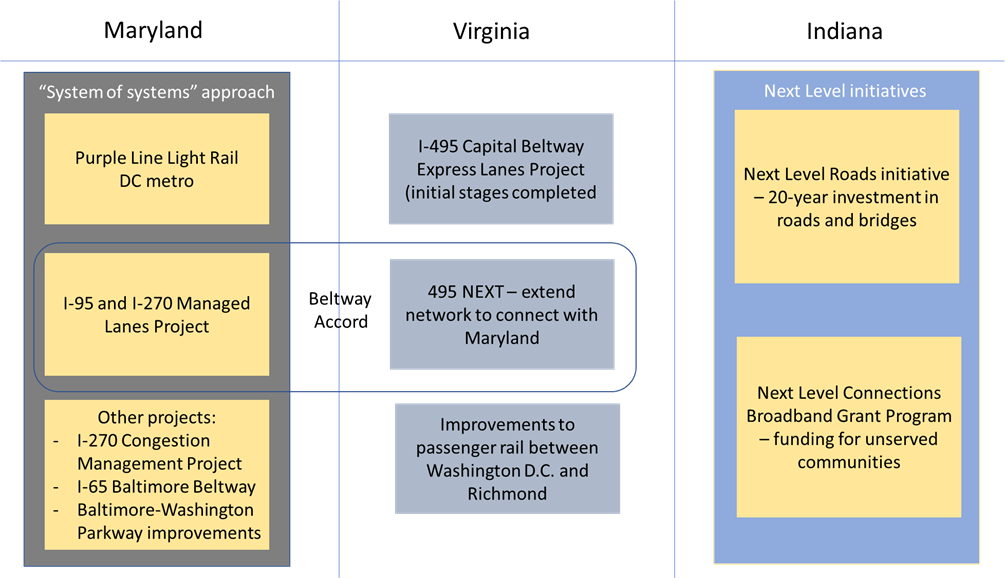

In the Washington region, Maryland has utilized a series of innovative public-private partnerships and private sector solicitations to improve the transportation network in the greater capital region. In 2015, Gov. Hogan directed the advancement of the Purple Line, a 21-station, 16-mile light rail project, through a public-private partnership. Using a variety of state, federal, private and local funding, the project is an example of engaging stakeholders to provide financial support for projects that deliver regional benefit. This remains the case even with the selection in November 2021 of a new design-build contractor to complete the project. The project will connect communities, economic centers, and major anchor institutions between two counties in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, and provide critical connections between the region’s Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Metro rail, Maryland Area Regional Commuter train, and local and regional bus network services. Gov. Hogan has also moved forward with Maryland’s complement to Virginia’s high-occupancy toll lane network, which provide dedicated voluntary lanes for high occupancy vehicles and those looking to get places faster through paying a variable fee. Anchored by the 2020 “Beltway Accord” between Gov. Hogan and former Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, Maryland’s “managed lanes” Traffic Relief Program is being undertaken with the specific goals of “reducing traffic congestion, minimizing impacts to the corridor and accelerating delivery, while pursuing shockingly innovative approaches at no net cost to the State of Maryland.” The project is being delivered through a public-private partnership and will build dedicated managed lanes on Maryland’s portion of the Capital Beltway (I-495) and along I-270, which links the beltway with Montgomery County, in addition to widening the American Legion Bridge over the Potomac River.

Maryland’s Traffic Relief Plan — A System of Systems

Gov. Hogan’s Traffic Relief Plan, along with other major projects such as the Purple Line, are best viewed as a “system of systems,” which delivers a series of innovative solutions for Maryland residents. Notably, the Purple Line and improvements to I-495/Capital Beltway and I-270 were originally part of a combined, comprehensive study in 2002. While the highway and transit components were subsequently broken up and the Purple Line was advanced as a standalone project, Gov. Hogan ultimately determined to move forward with both projects. Combined with the I-270 Innovative Congestion Management project (discussed below), as well as improvements to the I-695 Baltimore Beltway, the requested transfer of ownership and major upgrades to the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, and a state-of-the-art “Smart Signal” network along key corridors throughout the state, this “system of systems” will deliver transformational traffic congestion relief, public transportation, economic development, safety and improved quality of life for commuters in the region.

System-Wide Interstate Improvements in Virginia

Across the Potomac River, Virginia has a long tradition of undertaking megaprojects to support system-wide improvements to the transportation network. Completed and opened to traffic in November 2012, the I-495 Capital Beltway Express Lanes project built four new high occupancy traffic lanes (two in each direction) along a 14-mile stretch of the Capital Beltway in Virginia. The project replaced more than 50 aging bridges and overpasses, added pedestrian/bike access for all overpasses crossing the beltway, and tripled sound wall protection for adjacent communities. The public-private partnership relies on tolls in the new lanes to support construction, operations and maintenance over a 75-year period.

Virginia is moving forward on the I-495 Express Lanes Northern Extension (495 NEXT) project, which will extend the lanes north to the American Legion Bridge, connecting with Maryland’s planned program under the Capital Beltway Accord discussed above. On March 14, 2022, Governor Youngkin led a groundbreaking ceremony for the project, noting that “The 495 NEXT project represents the Commonwealth’s commitment to improving regional infrastructure and traffic flow for Virginians, our visitors, and the broader business community. Together with our partners from the public and private sectors, we are prioritizing investments in Virginia’s transportation network to keep people, goods, and our economy moving.” In December 2021, the Virginia Department of Transportation also launched an environmental study to determine the cost and identify financing options for an expansion of 495 Express Lanes to the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge, which would add another 11 miles to Virginia’s system of high-occupancy toll lanes.

On the rail side, in 2021 Virginia signed a partnership with CSX to deliver a $3.7 billion investment in the region’s rail network. By partnering with the railroad, as well as Amtrak and federal, state and regional stakeholders, the agreement will double Amtrak train service in Virginia. This will provide increased service between Washington D.C. and Richmond, add weekend service and bolster rush hour service for VRE along the I-95 corridor, and lay the foundation for future high-speed rail to North Carolina—all while preserving critical freight rail connections. Key infrastructure investments of the deal include building a new Virginia-owned Long Bridge across the Potomac River, with tracks dedicated exclusively to passenger rail, acquisition of more than 386 miles of railroad right-of-way and 223 miles of track.

Together, Virginia and Maryland are advancing the projects to form a congestion-free network for transit buses and carpools and enhance connectivity and competitiveness throughout the region.

Next Level Roads Initiative in Indiana

In a state known for consistently maintaining high ratings in infrastructure quality, Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb is delivering his Next Level Roads initiative, a comprehensive fully funded 20-year investment in Indiana’s roads and bridges. Utilizing a data-driven approach to maintaining, operating and improving the entire statewide system, Next Level Roads will invest $60 billion in the state’s highways. In addition to channeling 90% of the investment to improving the existing network, Next Level Roads will finish critical capacity improvement plans, such as accelerating the completion of I-69 as well as making safety and traffic flow improvements to U.S. 30 from Fort Wayne to Valparaiso and U.S. 31 between Indianapolis and South Bend.

Along the way, Indiana has taken a “best practice” approach to look at the state’s infrastructure asset portfolio as exactly that—an asset portfolio to be maintained and called upon to yield returns for residents and visitors. By viewing his team’s responsibility as more than preserving pavement, Gov. Holcomb grounds his infrastructure investments in economic opportunity and a sense of community benefit. He also places Indiana in the larger context of national and even international importance, through tying infrastructure investments to the state’s moniker as the “Crossroads of America.”

Gov. Holcomb is bolstering his Next Level infrastructure initiative by investing a combined $270 million in improving broadband access and adoption throughout the state. The Next Level Connections Broadband Grant Program will provide funding to eligible providers in areas of the state that lack quality, reliable access to broadband service, with priority to projects providing “100/100” Mbps upload and download speeds, and projects that provide connections to schools and/or rural healthcare facilities.

BEST PRACTICE

Since infrastructure investments are critical to the health of a state’s economy and the quality of life of its residents, Governors have demonstrated taking a strategic and holistic view when making these investments. This is done through developing whole-of-government infrastructure plans supported by funding and financing measures, and/or through adopting a system-wide or regional approach to infrastructure investments which consider the broader implications of specific investments on the state.

Chapter 3 – Setting Up for Success

Major infrastructure investments are herculean undertakings, with individual projects involving a diverse team of planning, engineering, design and construction firms. Supporting these efforts are teams of attorneys, procurement specialists, financial experts, communications and government relations professionals, and oversight consultants that provide direction and insight while keeping state decisionmakers informed of progress, setbacks and potential challenges on the horizon. These initiatives can be beyond business as usual at state agencies charged with delivering big infrastructure, and necessarily should be treated as such. If a state embarks on an ambitious new planning and funding mission to rebuild state infrastructure, each effort can be tied back to that mission and woven together to form one cohesive narrative. The same goes for major projects that are not necessarily associated with a larger initiative, especially those generational projects or those that utilize complex financing and funding mechanisms, such as public-private partnerships.

Major Project Divisions

An example of innovative governance arrangements for major infrastructure projects is Indiana’s Major Projects Delivery Division, which is housed within Indiana’s Department of Transportation. The unit was established to develop, manage and execute the department’s most complex road and bridge projects. The division has a heavy focus on stakeholder engagement, both internally and externally, and has established a six-point criteria to guide its mission. This includes establishing internal and external accountability and risk management measures, engaging in partnership, ensuring consistent and effective stakeholder communication, driving competition and maintaining an effective and efficient public involvement process. Adherence to these principles has fostered an environment of partnership and collaborative problem-solving. Establishing a structure where top officials integrate these goals and approaches throughout the lifecycle of major projects can result in success for all stakeholders.

Virginia’s Office of Public-Private Partnerships is responsible for developing and implementing a statewide program for project delivery. The office, which is sited in the Virginia Department of Transportation, works with a range of government stakeholders, including the Virginia Department of Transportation, Department of Rail and Public Transportation, Department of Aviation and the Virginia Port Authority to focus on public-private partnerships across all modes of transportation. It also focuses on non- transportation projects, such as solar energy development and cell towers/wireless projects in collaboration with a diverse range of state agencies.

The table in Appendix A presents the different objectives and functions of the Indiana’s Major Project Delivery Division and Virginia’s Office of Public-Private Partnerships.

Multi-Agency Coordination

Many major infrastructure investments are multifaceted, with different agencies serving different constituencies and with different priorities. This often requires multiple agencies working together behind a shared vision—most often under the direction of the Governor. For example, when Vermont Governor Phil Scott announced $2.4 million in electric vehicle charging station infrastructure grants, he tasked not one, but four agencies with working together toward a shared vision. After three years, the program has seen incredible success, with Vermont holding claim to having the most electric vehicle changing stations per capita in the nation.

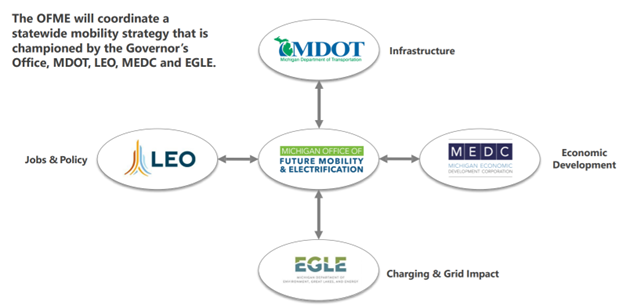

In Michigan, home of the Motor City of Detroit, Governor Gretchen Whitmer created the Office of Future Mobility and Electrification. The office coordinates a statewide mobility and electrification strategy, including expanding Michigan’s smart infrastructure, accelerating electric vehicle adoption and bolstering Michigan’s mobility manufacturing core. The office works across state government, academia and private industry, and builds on the state’s existing mobility initiatives. This includes Michigan Department of Transportation’s work developing smart infrastructure, the Department of Labor and Economic Opportunities’ work on economic competitiveness, and the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy’s progress on electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

Since its formation, the Office of Future Mobility and Electrification has formed partnerships with industry leaders and public agencies to advance key priorities. This includes partnering with other departments to implement Gov. Whitmer’s Lake Michigan EV circuit program—a network of EV infrastructure along Lake Michigan and in key tourism clusters. The office has also teamed up with the Department of Transportation, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, the Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity, and Cavnue, a subsidiary of Sidewalk Infrastructure Partners, to develop a corridor for connected and autonomous vehicles in Southeast Michigan. This public-private partnership will test technology and explore the viability of a more than 40-mile driverless vehicle corridor between downtown Detroit and Ann Arbor.

Figure 2: Michigan’s Office of Future Mobility and Electrification works with multiple state agencies and the private sector

In response to the passing of the IIJA, a number of states have created new positions and governance arrangements for state use of funding under the Act. For example, New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham announced new cross-cutting administration leadership to focus on infrastructure priorities. The Governor appointed Martin J. Chavez as the state’s new infrastructure advisor situated in the Governor’s office. He will work with communities around the state to determine priorities for the billions of dollars in federal infrastructure funding coming from pandemic relief and the IIJA. Matt Schmit will be the state’s broadband advisor to the new state Office of Broadband Access and Expansion. The new office will centralize and coordinate broadband activities across state government agencies, local government bodies, tribal government organizations and internet service providers. Gov. Lujan Grisham also appointed Mike Hamman as the state’s water advisor to work closely with federal, tribal, state and local agencies to improve the water infrastructure of the state.

Arkansas Governor and NGA Chair Asa Hutchinson issued an Executive Order establishing the Governor’s Infrastructure Planning Advisory Committee. The committee is composed of state agency personnel to identify best practices and procedures to ensure the state of Arkansas realizes the maximum relief and benefits available under the IIJA. Maryland Governor Larry Hogan signed an executive order establishing the Governor’s Subcabinet on Infrastructure, consisting of state agencies that will administer funds and advise on the implementation of the federal Infrastructure Investment And Jobs Act (IIJA), and named Deputy Chief of Staff Allison S. Mayer as infrastructure director. Many Governors have appointed dedicated IIJA Coordinators to oversee implementation of their state’s infrastructure investments.

The National Governors Association IIJA resources page provides information on governance arrangements being implemented by states and territories for implementing funding allocated from the Act and is updated regularly.

Cross-Border Partnerships

Recognizing the importance of cross-border partnerships, a five-state collaboration including Illinois Governor JB Pritzker, Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer, and Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers signed a Memorandum of Understanding to accelerate vehicle electrification in the Midwest in September 2021. The Regional Electric Vehicle Midwest Coalition creates a regional framework to accelerate vehicle electrification across the Midwest, which is to be informed through industry, academic, and community engagement. The coalition will focus on accelerating medium and heavy-duty fleet electrification, elevating economic growth and industry leadership, and advancing equity and a clean environment.

Looking internationally, Gov. Whitmer deepened a longstanding cooperative partnership with the neighboring Canadian province of Ontario, to advance automotive and mobility technologies and help people and goods move safely and efficiently across the border by land, air and water. As part of the initiative, Ontario’s Autonomous Vehicle Innovation Network and Ontario’s Ministry of Transportation will begin a multi-year effort to deploy smarter and greener technologies at the border and develop a Memorandum of Understanding to explore the implementation of a cross-border, multimodal testbed for advanced automotive and mobility solutions.

BEST PRACTICE

Governors are establishing teams within state government dedicated to shepherding major infrastructure investments, whether on a project basis or as part of an overall multi-agency initiative. The complexities around finance, project delivery and operations of major infrastructure projects typically fall outside the “business as usual” operations of the state and require far greater attention to stakeholder involvement, media and intergovernmental relations as well.

Chapter 4 – Building Partnerships to Get the Job Done

Delivering big infrastructure requires a comprehensive, all-hands-on-deck approach to funding, financing and delivery of major projects. The major project development and delivery offices we looked at in the previous chapter should be designed to build strategic partnerships that help maximize the value of an asset portfolio. This section will look at the myriad funding, financing, and partnership mechanisms that can come together to form a solid infrastructure foundation.

Funding

Infrastructure “funding” concerns the ultimate source of project revenue, such as gas taxes or toll collections. Infrastructure “financing” on the other hand is about the structures put in place to accommodate a mismatch between upfront costs and source revenues, such as through state borrowing or P3 arrangements, which will be discussed later.

Infrastructure investments are ultimately funded in various ways across different sectors. Transportation infrastructure in most states utilizes a separate trust fund comprised of user fees such as motor fuel taxes, vehicle registration fees and other sources. These traditionally lucrative funding streams have often been beset by diversions to accommodate other pressing needs and priorities. At the same time, the purchasing power of those funding sources has been diminishing steadily over the last several decades. The federal government, recognizing the critical need for funds to cover growing surface transportation infrastructure needs, have on several occasions transferred monies from the general fund to cover deficiencies in the Highway Trust Fund (most recently through the IIJA).

Beyond transportation projects, more than 50,000 active drinking water systems (not including more than 100,000 non-community water systems, such as those supplying schools and hospitals) and nearly 15,000 wastewater treatment plants throughout the U.S. are funded by user fees that are collected by local governments. In addition, there have been an increasing number of state and municipal broadband networks supported/built out by state and local general funds. In one unique case in Maryland, many environmental resilience projects are funded by local fees and taxes and administered by the quasi-state agency Maryland Environmental Service.

Recognizing the need for federal support to rebuild America’s crumbling infrastructure, as noted earlier, President Biden and a bipartisan group of Senators, with the bipartisan support and collective input from the nation’s Governors, negotiated and passed the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). The legislation addresses many of the Governors’ policy priorities, including funding and financing needs, fixing existing infrastructure and investing in the future, streamlining project delivery, and encouraging innovation. Despite this generational funding opportunity, many have expressed the view that these funds will nonetheless be insufficient to address existing infrastructure gaps, and that partnerships not only with the federal government, but with the private sector and stakeholders at the local level will be of paramount importance as a force multiplier to help not only restore the country’s infrastructure, but place states and territories on a fiscally sustainable long-term path. The key to this success will be working to make each of these sources of funding and financing work best across the portfolio of infrastructure assets.

Securing Funding from Multiple Stakeholders

In Maryland, growth at the Port of Baltimore has been limited by a lack of double-stack freight rail capacity through the Howard Street Tunnel. In 2019, after important breakthroughs in engineering approaches significantly decreased the cost of tunnel improvements, Maryland received a critical federal INFRA grant that allowed the state to enter into an agreement with CSX, the railroad that owns the tunnel, and the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, to expand the tunnel as well as address capacity constraints along the I-95 rail corridor up through Pennsylvania. Completion of this $466 million project will be a game-changer, creating thousands of jobs and contributing millions to the regional economy, and allow the Port of Baltimore to capitalize on its strategic location as the most inland port on the east coast. This will mean that containers will be able to be more easily transported via rail to America’s heartland and will assist with addressing current supply chain issues across the nation. The project broke ground in November 2021 and is expected to be completed in 2024. A key to the project’s success was the collective funding contributions from all stakeholders that will see benefits.

In Washington, two of the state’s economic engines, the Port of Tacoma and Sea-Tac International Airport, suffered from poor connectivity along congested roadways. In response to these challenges, Washington commenced the Puget Sound Gateway Program, which will build capacity on two critical roadways, the SR 167 Completion Project and the SR 509 Completion Project, to complete critical missing links in Washington’s state highway and freight network. To facilitate the program, the state of Washington combined four different sources of funding: approximately $1.5 billion from the “Connecting Washington” funding package signed into law by Governor Jay Inslee in 2015; $180 million from new tolls; $130 million from local contributions and grants as well as federal grant funding.

Overall, the $2 billion program will help Washington state compete both nationally and internationally by enhancing regional mobility, shoring up critical freight connections, utilizing intelligent tolling solutions, and growing local economies and jobs. In the effort to bring the project across the finish line, the Washington State Department of Transportation gathered key stakeholders to champion the projects, including operators at the Port of Tacoma, customers of the Port from Washington’s vital agriculture community, the trucking industry, and local elected officials.

A Two-Way Street: States Supporting Local Governments to Improve Community Well-Being

Many states offer opportunities for local governments to participate and drive projects that fall somewhere “in-between”—not quite large or complex enough for significant state resources, but meaningful and impactful to local communities that don’t necessarily have the funding to tackle them on their own. In several states, federal fund swap programs allow local governments to benefit from federal funding using state department of transportation federal funding dollars, which come with more navigable requirements and less red tape. A study by the Government Accountability Office in 2021 found that between 2016–2020, a total of 15 states utilized fund swap programs for local governments.

Other states utilize direct grant programs for local governments. For example, Kansas employed their Cost Share Program in 2020 to famously alleviate a deluge of train whistles from a local community. When a railroad increased service around the town of Belle Plaine, residents sought a number of solutions to mitigate the impact, and ultimately settled on seeking a Quite Zone designation from the Federal Railroad Administration. To help with the cost of implementing $160,000 in required safety infrastructure improvements, the state of Kansas came through with a Cost Share grant, which, with adulation from local residents, saved the day and marked the beginning of a rebranding and revitalization of the city.

BEST PRACTICE

Governors are strategically working with federal and local governments, the private sector, and other key constituencies to leverage funding and financing, manage and allocate risks, and incorporate long-term resiliency into projects and initiatives. This has increased stakeholder buy-in for projects but also enhanced their attractiveness when competing for funding through federal discretionary funding programs.

Public-Private Partnerships and Innovative Financing

Public-private partnerships (P3s) are a form of government procurement to build and implement infrastructure using the resources and expertise of the private sector. The Federal Highway Administration defines a P3 as a long-term contract that may include development (design and construction), operation and/or maintenance of a facility, and involves a component of private financing. For major infrastructure projects that fall outside the “business as usual” of government service provision and maintenance, public-private partnerships have shown to be beneficial in the right circumstances. Potential benefits of P3s include:

- Bridging financing gaps in the face of debt limitations through attracting private investment capital.

- Encouraging innovation, greater asset utilization and integrated whole-of-life asset management through improved management and operations.

- Facilitating “value for money” outcomes for the community through assigning risks to the partner best equipped to manage and mitigate potential damage from those risks. If risks are assigned appropriately, private incentives can lead to a reduction in project costs, improved timeliness and greater efficiencies in service delivery.

- Maximizing public and private positions on taxing structures through allowing a private partner to claim ownership for tax purposes of a road or other type of infrastructure and claim tax benefits (as it would if it owned the infrastructure outright). In this way, “State and local governments can share in the gain from that reduction in tax liability when, as a result, they receive higher bids for a lease than they would otherwise.”

The Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in Carolina, Puerto Rico offers an example of a project that has been able to generate additional revenue for the Territory and improve service delivery through a P3 concession with the private sector. In 2013, through the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration Airport Investment Partnership Program, Puerto Rico entered a P3 for the long-term concession to finance, operate, maintain, and improve the airport, which is located just three miles from the capital city of San Juan. Upon execution of the agreement, Puerto Rico received $615 million in an upfront leasehold fee, and an annual payment of $2.5 million for the first five years of the agreement, along with 5% of revenue over the next 25 years, and 10% in the final 10 years. In addition, as part of the agreement, Puerto Rico’s private sector partner made an upfront investment of approximately $400 million to renovate terminals, upgrade baggage scanning and improve retail facilities. Another $200 million improvement and expansion plan, including runway reconstruction, structural repairs and terminal renovations will be completed over the next five years. Since entering into the airport P3, the airport has increased passenger counts and its standing in the region as an international gateway.

The Indiana Toll Road offers an example of a P3 concession which has improved whole-of-life asset management outcomes through facilitating investment in strategic capital projects. The Indiana Toll Road project is a 157-mile divided highway that was built in 1956 and spans Northern Indiana from the Ohio to Illinois borders. It was leased by the state of Indiana as a concession in 2006 and acquired by IFM Investors in 2015 through a restructuring. Since working with the private sector to improve, maintain and operate the Indiana Toll Road, the facility has undergone several rounds of capital investment, including an initial $275 million investment in improving roadway quality, $75 million in rest-area and truck parking facilities improvements and the recently completed $34 million fiberoptic communications system linking the entire network from border to border. By 2025, it is expected that 95% of the toll road’s pavement will be entirely reconstructed and will rank among the best in the nation.

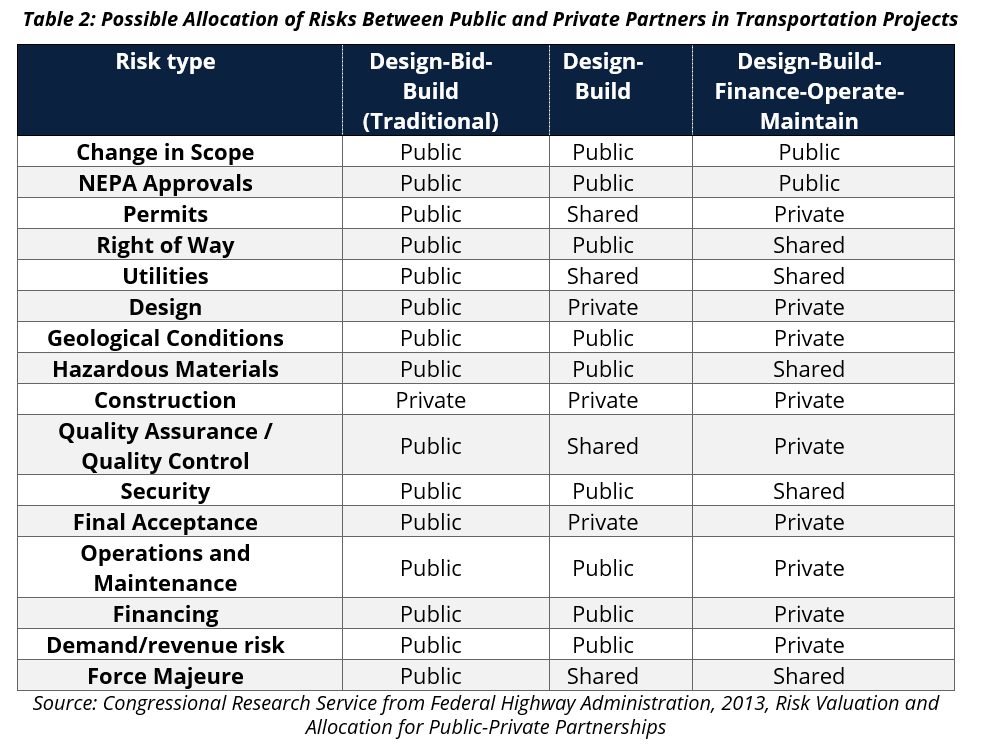

In Colorado, the Department of Transportation wanted to achieve a complete corridor solution to Interstate 70 East over a 10 mile stretch in Denver—one of the most heavily travelled and congested highway corridors in the state. In assessing the project, the department considered a range of delivery options, including design-build, design-build-operate-maintain, and design-build-finance-operate-maintain, using a Value for Money analysis. This type of analysis sought to understand which approach would deliver the greatest value to the state over the lifecycle of the project. They key variable between the options related to what risks could be appropriately transferred to the concessionaire, such as construction, operations, maintenance and rehabilitation risks, and whether the transfer of these risks ultimately reduced the costs and cost contingencies facing the public sector (see table above on possible risk allocation approaches). The Value for Money analysis for I-70 concluded that the project was not affordable under a design-build model, but that it could proceed under both a design-build-operate-maintain and design-build-finance-operate-maintain models. The analysis also found that the later model provided more risk transfer and certainty to the Colorado Department of Transportation. In 2017 the Department of Transportation reached financial close for a design-build-finance-operate-maintain concession with Kiewit Meriam Partners and construction is expected to be completed in 2022.

A Global Perspective

Public-private partnerships (P3s) have been successfully implemented worldwide, on a variety of infrastructure projects. These include both user-charge or “economic infrastructure” P3s such as roads, energy and water, as well as availability payment or “social infrastructure” P3s including schools, hospitals and courthouse facilities. P3s have been employed to develop new infrastructure projects or to improve and/or enhance the operation of existing facilities.

A report recently released by the Global Infrastructure Investment Association and DLA Piper provides an overview of the global infrastructure investment market and the different approaches taken with P3s. This paper found that among eight large P3 markets there were around 50 projects that closed with a value of around $26 billion in 2020. Apart from the U.S, two of the largest markets for P3s globally are Australia and Canada.

There is a long history and significant experience in the use of P3s in Australia. On average around 10% of total government infrastructure procurement are P3s, with a focus on large scale or mega projects (for example, the Westconnex motorway system in Sydney). P3 projects are generally viewed favorably in Australia given their focus on providing value for money for the taxpayer through appropriate risk allocation. Australian P3s have generally performed well, with average construction cost overruns and construction delays significantly lower than traditional projects. P3s have occasionally been criticized in Australia on the basis that governments can borrow more cheaply than the private sector can. However, the public sector comparator used to assess Australian P3s adds on a “premium” for the implicit risk that the public sector bears in any potential project to ensure a like-with-like comparison between procurement options.

Like Australia, Canada has a robust P3 market which has developed since the late 1990s. There are currently over 100 P3 projects across all sectors and regions in the planning, procurement or construction phase. Projects in Canada are based in most part on availability payment models where users of the facility do not shoulder the costs directly, and there appears to be little appetite for this approach changing. Canadian P3s often include community benefits as key contractual commitments, such as the use of apprenticeship programs or the use of labor from under-represented groups. Increasingly, the market has moved to one where project contractors take ownership positions in the private sector component of the project, rather than one driven by pure equity investors. Overall, there has been a good track record of delivering projects on time and on budget through the P3 model, and the use of this type of procurement approach is viewed very favorably in Canada.

The recently passed bipartisan IIJA incorporates several provisions that promote the use of P3s. This includes a new requirement for projects over $750 million and seeking financing assistance through Transport Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act or Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing programs to complete a value for money analysis, which requires assessment of different procurement options. The IIJA also incorporates a new five-year $100 million technical assistance program to assist states, localities and tribal governments with innovative financing and asset concession planning. Additionally, the law requests that the Secretary of Transportation submit to Congress an “Asset Recycling Report”, that includes an analysis of impediments to increasing the use of public private partnerships in transportation and proposals for approaches that address those impediments.

During Maryland Governor Larry Hogan’s 2019-2020 Chairmanship, NGA led an international study tour to Australia to explore the country’s innovative approaches for developing, securing and financing roads, mass transit, ports and other infrastructure. Gov. Hogan visited Australia in support of his initiative as NGA chair, Infrastructure: Foundation for Success, which sought to build on international successes in furnishing and maintaining the physical assets that are crucial to economic competitiveness and quality of life in states and territories.

Gov. Hogan and other U.S. leaders, including Colorado Lieutenant Governor Dianne Primavera, Louisiana Secretary of Transportation and Development Dr. Shawn Wilson, and Washington Secretary of Transportation Roger Millar, visited Port Botany, the WestConnex civil works project and Sydney Metro’s Martin Place station to learn about innovative tools Australia uses to finance major infrastructure projects and explore modern construction approaches. One of the areas of focus was Australia’s asset recycling program, in which a state sells or leases assets such as ports and airports to the private sector and applies the proceeds toward new infrastructure, using incentives from the federal government. Investment is enabled in Australia by the presence of multi-billion-dollar “superannuation” funds that are essentially compulsory retirement savings accounts.

BEST PRACTICE

When considering the use of public-private partnerships, many states and territories are adopting the practice of identifying which parties are best able to manage risks and distribute such risks accordingly. This can create the right incentive structures and thus lead to project efficiencies in both time, money and innovation that will pay off in the long run. State efforts have demonstrated that good project management and strong partnerships are necessary ingredients to the success of any major project.

State Bonding Initiatives

As examined in NGA’s prior memo on funding and financing mechanisms, states and territories rely on a variety of financing options to complete projects, typically with low cost or tax-exempt interest rates. Every state issues tax-exempt municipal bonds to finance capital for transportation projects, fund day-to-day operations, or both. There are a variety of bond structures used for transportation, including general obligation bonds, revenue bonds, and federal debt financing tools, such as private activity bonds and Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicle bonds.

As discussed in Chapter 2, Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan utilized administrative actions to issue state road bonds to generate $3.5 billion in additional funds for road improvements, with the purpose of adding or expanding 122 major new road projects. During her 2020 state of the state address, Gov. Whitmer said that the “Rebuilding Michigan plan will ensure we start moving the dirt this spring and save us money in the long run.” A release from the Governor’s office observed that “moving projects ahead 4-6 years allows MDOT to save taxpayers money by avoiding the annual cost of inflation.”

In 2020, Connecticut authorized up to $1.6 billion in special tax obligation bonds for transportation infrastructure improvements, covering FY2020 and 2021. Improvements included highway and bridge construction and maintenance, mass transportation and transit facilities, waterway facilities, and DOT maintenance and administrative facilities. Debt service on these bonds is paid from the dedicated revenue stream of the Special Transportation Fund, including motor vehicle fuels tax and oil company taxes. According to a report by state Treasurer Shawn T. Wooden, state treasurer’s office bonds help leverage federal funds by providing the required state match for federal transportation funding, and that this will be important as the state looks to take advantage of the significantly expanded funding coming from the IIJA.

Maine Governor Janet Mills signed legislation placing a $100 million bond issue on the ballot, which was approved by Maine voters in November 2021. The bond measure dedicates $85 million for surface transportation, construction and maintenance and $15 million for pedestrian, bicycle, port, rail and aviation facilities. Funds derived from this bond will form a critical part of the agency’s three-year work plan and will allow Maine to leverage up to $250 million in federal funding. Also, in early 2022, the Hawai‘i Department of Transportation said that its Airports Division had sold new Airport System Revenue Bonds to fund $230 million of essential capital projects to modernize and expand air service facilities statewide. The bonding measure also took advantage of low interest rates in the municipal bond market to refinance $57 million in prior bonds with associated cost savings.

In May 2021, Lois Scott, chair of the Milken Institute’s Public Finance Advisory Council and former chief financial officer for the City of Chicago suggested that “with a cohesive federal infrastructure strategy, favorable bond markets and greater understanding of state and local budget realities, the vital signs [in state and local financing] will improve substantially.” She suggested that “facilitating their access to capital lies at the very heart of creating greater equity in our communities,” and provided several insights into how states and local governments can capitalize on the fact that the municipal bond market is a high performing asset class. In particular, she underlined the importance of putting “a big gold star on the cover of every municipal bond prospectus highlighting the good it is doing for that community and setting it apart from investments in corporate bonds to buy back stock.”

Green Bond Market

Some states are entering the growing “green bond” or “climate bond” market, funding projects with environmental or climate-related benefits ranging from clean or renewable energy installation to energy-efficient building programs. These bonds are structured traditionally but are affixed with the climate or green labels by the issuer or conferred by a certifying organization. These bonds allow states to signal the importance of the environmental outcomes of a given project or suite of projects to potential investors.

In New Jersey, the Murphy Administration sold $122.5 million Environmental Infrastructure Bonds in June 2021. The bonds will leverage Department of Environmental Protection zero-interest loans to provide a total of $386 million in projects financed through the Water Bank. The projected funded include green infrastructure, sewer system collection and treatment improvements, drinking water treatment and distribution system, enhancements and projects to reduce sewer overflows.

In 2019, the Connecticut Green Bank achieved Climate Bond Standard Certification for $38 million issued through the state’s Solar Home Renewable Energy Credit program. The proceeds are being used to fund the Residential Solar Investment program, which was created to fulfill state policy adopted in 2015 that mandated the installation of 300 MW of new residential solar by 2022. The Green Bank is moving to accomplish this ahead of schedule, and will track job growth, tax revenue generation, air pollution reductions, public health improvements, and equitable access to clean energy arising from the program.

In 2018, the World Bank announced a partnership with the state of California to invest $200 million in World Bank green bonds, pushing the total amount of green bonds purchased by the state to $1.5 billion. These bonds provide California with competitive yields while supporting the growth of a sustainable low carbon economy. In announcing the move, then California State Treasurer John Chiang acknowledged that “we must build, so let’s build green. Let’s build to protect ourselves from rising sea levels, from extreme weather, and to ensure prosperity for our children and grandchildren.”

BEST PRACTICE

States and territories have started highlighted the value that investment in the public sector will have on the larger societal and social good when issuing debt. This can be through debt issued through green or environment bonds, which are targeted to certain initiatives such as environmental remediation or clean energy.

State Revolving Loan Funds and Infrastructure Banks

State Infrastructure Banks are revolving funds established and operated by a state (frequently within a state’s department of transportation, or equivalent agency) with the capacity to offer direct loans and various forms of credit to finance infrastructure projects. State infrastructure banks can benefit from direct federal funding and federally-sponsored financing, such as TIFIA. Like economic development authorities, state infrastructure banks can support a variety of state and local governments and regional entities with responsibility for developing and delivering infrastructure solutions.

At the start of 2021, Nevada Governor Steve Sisolak reinvigorated the Nevada State Infrastructure Bank with $75 million to create a “robust pipeline of critical infrastructure projects that will put people to work.” The funding of the state infrastructure bank will allow state and local infrastructure projects to be prioritized centrally and will potentially allow the state to best maximize federal dollars dedicated to infrastructure. This investment of $75 million is projected to allow Nevada to advance up to $200 million in new infrastructure investments in 2021, and a combined $1 billion in new investments over the next five years, creating more than 30,000 jobs by 2031.

In 2017, the Indiana Finance Authority applied to the Environmental Protection Agency’s water financing program, “WIFIA” (Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act), and received a $436 million loan. WIFIA funds support larger state-wide projects and projects with regional significance. Combined with the state’s uncommitted State Resolving Fund balance of $453 million, the loan allowed Indiana’s Finance Authority to lend nearly $900 million to 23 wastewater and drinking water projects across the state, serving a combined 1.2 million people.

In 2019 and 2020, several states followed this approach, including the New Jersey Infrastructure Financing Authority, the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank, the Iowa Finance Authority, and the California State Water Resources Board. These states all applied to WIFIA loans with a mixture of projects that were eligible within their clean water and drinking water state revolving funds.

Chapter 5 – Navigating and Driving Procurement For Results

Harnessing Innovation in Procurement Methods to Drive Delivery Outcomes

Traditional procurement of infrastructure delivery in the U.S. is based on a lowest cost/price model, with most state agency regulations focusing heavily on price in evaluating project bidders. What transpires often, as a product of this framework, are low bids that often involve varying numbers of change orders throughout the project delivery phase, or contractors overextending capacity as a result of winning several bids at the same time. The result is often that resources will be spread throughout many projects, with each progressing on a schedule based on the resources available.

Increasingly, states have been undertaking procurement based on factors beyond simply upfront costs. For example, on a “time plus money” or “A+B” value proposition, bidders are encouraged to include additional resources into a project to achieve a nearer-term completion. Public entities are also increasingly examining the total cost of ownership for a given project, including maintenance and operating costs, and incorporating performance-based metrics into the contract to ensure the delivery of services. This includes through the adoption of public-private partnership (P3) procurement approaches that were discussed earlier in Chapter 4.

These procurement models are often referred to as “best value procurement” approaches, where the relevant agency makes award decisions based on a variety of factors to maximize outcomes to the public beyond simply the lowest upfront cost. By shifting focus away from a strict cost perspective, a best value procurement approach can encourage bidders to develop a project delivery plan that matches the priorities of the public entity. As projects become more complex, these analyses will become essential tools in the state’s toolbox. Additional criteria, such as environmental impacts, long-term sustainability and resiliency benefits, and adaptability to business growth and planned development, can also be added to the mix.

While innovative procurement models may not necessarily be the ideal approach for every project, their consideration can be part of an assessment of project delivery approaches. Several states have established a best value screening criteria to assess how projects should be procured. In Minnesota, an analysis related to agency experience, private sector experience, and several quality enhancements plays a role in determining what procurement approach to adopt. Similarly, Indiana utilizes a design-build best value screening process that looks at managing risk, schedule, cost, lifecycle performance, design solutions and market considerations, among others, to analyze whether to move forward with best value procurement. And as discussed above, for larger scale infrastructure projects, states are increasingly undertaking value for money assessments to determine whether private financing models will generate greater benefits to communities than traditional procurement.

Another approach is to not only look at best practice procurement for individual projects, but to consider best practice procurement for a portfolio of projects. For example, in 2012 Pennsylvania adopted a PA Rapid Bridges bundling project to tackle system-wide state of good repair needs. This nearly $900 million public-private partnership has replaced more than 550 poor condition bridges over a period five years—a feat that would have taken an estimated 8–12 years under traditional procurement practices. The private partner is now responsible for general maintenance activities for the assets constructed for periods ranging from one to 25 years. Georgia had similar success with a bundled design-build approach that repaired 24 off-system bridges in just two years, at a total cost of $39.6 million. Missouri, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, Oregon and Rhode Island have also experimented with bridge bundling. The Federal Highway Administration has compiled a summary of takeaways and best practices from each of these projects.

Moreover, the Indiana DOT adopted project bundling as a standard practice as evidence suggested that bundling creates demonstrated value. A machine-learning platform uses the state’s historical and asset management data, along with business rules, to automate and optimize bundle selections over multiple program years. This approach has increased savings by 40%, leading to expected savings of $108 million over the next 4 years.

BEST PRACTICE

States and territories are increasingly taking a comprehensive look at state infrastructure as a portfolio of assets to manage, maintain and invest in. Each asset in the portfolio might need a different approach to operate, maintain, or rehabilitate. Some assets might be well-positioned to provide value to other assets within the portfolio. Taking this strategic approach can maximize value across the entire portfolio.

Driving Minority and Disadvantaged Business Enterprise Participation Through Procurement Policies

Just like choosing what infrastructure to invest in can achieve a diverse set of goals and priorities, a strategic approach to the how can be critical to driving the same results. Procurement policies can be a critical tool for increasing equity in infrastructure workforces by positioning small, minority-owned, women-owned, and disadvantaged businesses to effectively compete for projects. More inclusive procurement policies, including certification programs, local hiring requirements, and minimum award thresholds for minority- and women-owned businesses, can benefit from a best value project delivery approach, which allows for a more tailored tactic beyond the “lowest bid” delivery method.

A 2018 study from the Emerald Cities Collaborative looked at policies and best practices aimed at increasing minority-owned, women-owned, and disadvantaged business participation in infrastructure development and delivery. In looking nationally at inclusive procurement and contracting policies at the federal, state and local levels, the study made a number of findings and recommendations. It noted in particular that among diverse approaches at the state level, “Maryland has among the strongest policies in the country at both the state and local government levels because it has staff at all levels who are educated in best practices, and they take the time to advocate for implementing those practices at the local levels.”

The Emerald Cities Collaborative study also looked at the state of Washington, where the Washington State Department of Transportation has established a small business program to level the playing field for small enterprises. This includes “unbundling” contracts to assist small firms in bidding as prime contractors, abbreviated procedures to prequalify contractors for contracts under $100,000, a Small Works Roster program for contracts under $300,000, and a goal of 10% participation by small business enterprises certified by the Office of Minority and Women’s Business Enterprises on federally funded design-bid-build contracts without disadvantaged business enterprise contract goals. Washington’s Department of Transportation also has a Community Engagement plan, has established a disadvantaged business enterprise advisory group, and offers general and firm specific training and technical assistance to help these firms become more competitive. While success has been seen with breaking large contracts into smaller procurement opportunities, a 2021 study by the University of Maryland School of Engineering, in collaboration with the Maryland Transportation Institute, found that P3s have the potential to drive higher participation by disadvantaged businesses. The large size of most P3 infrastructure projects allows for more subcontracting opportunities, and increased community engagement and other measures bargained during the solicitation process create a model where “P3 offers an excellent vehicle to dispense transportation monies to small firms and bolster the economy.” While the study acknowledges its limitations in terms of having a relatively small sample size from which collect data, and that the results of the study are best (and perhaps only) applicable to large projects, the point of tailoring the procurement methods to the task and priorities at hand holds true.

BEST PRACTICE

Procurement policies and statutes that accommodate flexibility can be leveraged to support a variety of approaches to solving diverse needs. As states move to incorporate equity, long-term asset management, lifecycle environmental impacts, and broader community renewal and enhancement goals into projects and investments, integrating flexible procurement frameworks can improve these outcomes from the outset of a project or program.

Problem-Based Procurement

Two states have essentially flipped the procurement process on its head, focusing the procurement (or in some cases, avoiding a procurement altogether) on the problem, rather than the solution. Instead of tailoring a procurement around specifications for the solution being sought, “problem-based procurement” welcomes prospective bidders to propose innovative solutions to a well-defined problem.

The approach builds off a National Association of State Chief Information Officers’ 2018 View From the Marketplace report, which recommended that states “work with all parties—including those from the private sector—to establish a process that increases flexibility and communication” and “craft requests for information and requests for proposals in a manner that encourages solutions from the private sector rather than focusing on overly prescriptive specifications.” The process is “meant to run very quickly, [and is] meant to bring flexibility and creativity to the solutions that we get,” according to Connecticut Chief Information Officer Mark Raymond. This approach can create a productive dialogue while saving both the government and private sector time and headache.

Maryland employed this approach in the transportation sector to provide time savings on a congested highway and in the IT sector to avoid a costly procurement altogether. In 2016 Governor Larry Hogan announced the $100 million I-270 Innovative Congestion Management project, which incorporates both roadway improvements and innovative technologies to reduce congestion. The roadway improvements target 14 existing bottlenecks across the 34-mile corridor, using a “right-sizing” approach to maximize capacity and address safety. The project is an example of an innovative approach to soliciting improvements to complex challenges: the state issued a procurement that set only a fixed price and performance criteria, inviting the private sector to develop new methods to achieve objectives within the $100 million price.

In announcing the procurement, then-Secretary of the Maryland Department of Transportation Pete K. Rahn noted that “we’re trailblazing a new way of doing business that will be a model for projects across Maryland and for transportation projects all across the nation.” At the site, Gov. Hogan expressed his “[excitement] to see innovation in action when it comes to solving the problems of congestion here on I-270.” The project is currently 83% complete and is expected to be finalized by December 2022.

On the IT side, Maryland Department of Information Technology (DoIT) Secretary Mike Leahy utilizes this “problem-based” approach when agencies come to his department with proposed procurements. He asks at the outset that they explain “what it is you’re hoping to accomplish, in English, what work forms are involved, what data you need, what data you have and then we will help you.” This formula was used successfully at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic to save the state several million dollars and three to four months when the state’s Department of Commerce approached DoIT with a costly and timely solution to handling a deluge of COVID-related small business loan and grant applications.

The problem-based approach led both agencies to realize that they had a solution in-house—“we already had the black box to do 90% of it and the rest of it was a function of making sure we incorporated their workflows and their forms into the processes we already had in place.”

In California, on his first day in office, Governor Gavin Newsom, issued an executive order directing agencies to adopt an “Innovative Procurement Sprint” to identify solution-focused procurements related to emergency preparedness and wildfire preparedness. Citing “a pressing need for the state to identify innovative and sustainable solutions to address the state’s challenges of severe wildfires and degradations of forest health,” the order aimed to procure modern, innovative solutions. “Instead of asking for a particular technology product, as with traditional procurement, we can ask for solutions to a problem we face, convene state experts, vendors, entrepreneurs and scientists from a range of industries, and challenge them to propose innovative, technological solutions to yield more comprehensive and effective results,” stated Gov. Newsom in his order.

BEST PRACTICE